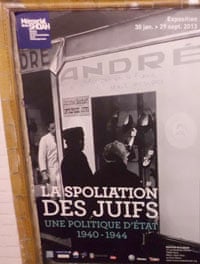

Passengers on the Paris metro have never been shy about responding in kind to the writing on the walls around them. But graffiti on posters advertising a new exhibition – La Spoliation des Juifs: Une Politique d'État, 1940-1944 (The Pillaging of the Jews: A State Policy, 1940–1944), at France's Holocaust museum – are more agitated than usual. While the posters aren't particularly more controversial than any other exploration of occupied France, they seem to have touched a raw nerve. Rather than focusing on Nazi or Vichy aggression and the overt violence of round-ups, internment and deportation, the exhibition illustrates state antisemitism as part of a much more public and conscious process.

In the poster, two people look through the windows of a well-known shoe shop, André, which carries a sign in German and French that reads "Jewish business". Here we are softly shown that the average Parisian could not have been ignorant of the intensification of antisemitic policies implemented by the French government during the second world war. The poster and exhibition implicate ordinary French citizens as accomplices to the Vichy state. In this way, La Spoliation stands out from earlier public displays of the Holocaust in France, and as a result reactions in France have been striking.

The bulk of the graffiti that we spotted falls into two distinct categories: mitigation and relativism. The first diminishes France's responsibility for the persecution of Jews under the Vichy government; the second links the "dispossession" of the Jews with the "dispossession" of Palestine by the Jews. These aggressive acts of graffiti serve neither memory nor victim.

"Do not forget that France was occupied" is the rejoinder on several posters, a sentiment with a long and controversial history in remembrance of the war years in France. For more than 50 years after liberation, France denied its ultimate responsibility regarding the deportation of more than 76,000 Jews. President Mitterrand famously referred to the Vichy years as a "parenthesis" that did not represent a true and republican France. A speech made by Jacques Chirac in July 1995 admitting the state's responsibility for the deportation of French Jews marked a significant change in the way that the French perceived their wartime history and led to the 1997 Mattéoli commission which ruled on the state confiscation of Jewish property.

But while multiple exhibitions and the trials of well-known collaborators in the 1990s exposed the active participation of French bureaucrats in the round-up of Jews, there is considerably less public coverage of the extended period of persecution prior to the deportations that began in 1942. The new exhibition and its posters remind us that ordinary French citizens were witness to the economic and psychological persecution carried out by the state. Yet these subterranean commentaries attempt to detract from the personal and collective responsibility of the state and its citizens.

The second theme set out in the graffiti is that state spoliation of Jewish property in France in the 1940s is akin to the spoliation de la Palestine by Israel today. Comments in the exhibition guest book suggest that it is a "shame" that the Jews are "doing the same thing" in Palestine. These comments seek to transpose the public memory and commemoration of the dispossession committed against the Jews 60 years ago on to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The implication is that the victim of the state has now become the perpetrator of state crimes.

Furthermore, these remarks imply that the historically "equivalent" property of the Palestinians is not shops nor personal effects, but land. In other words, the Palestinians are defined exclusively by their possession of their land, while the Jews remain defined entirely by their possessions. Jews are here denied a geographical belonging: they are neither French, nor legitimate possessors of land in Israel.

The drawing of an equivalence between the Jews of yesterday and the Palestinians of today is not unique to France. It seems that public commemorations of the Holocaust are rarely free of those attempting to diminish the suffering of Jews in Europe by referring to Palestine (as we saw in the comments by the British MP David Ward about this year's Holocaust Memorial Day, for example). Not only does this diminish the moral worth and historical significance of preserving the memory of crimes committed in Europe against the Jews, it does not serve the Palestinian cause as it, too, is profoundly distorted by association with a history that is not its own. This parallel would suggest that we are asked to blame the Jews of Europe for another people's loss, and therefore any public commemoration of these historic crimes no longer has significant currency.

By attempting to remove sympathy for the Jews by situating them as the new aggressors, both types of graffiti daubed on these posters attempt to absolve the perpetrators of the Holocaust and its collaborators. Even before the graffitied posters eventually come down and these temporary commentaries are lost, we should remember that this aggressive competition for a memory of persecution betrays a disingenuous and dangerous approach to history and justice.