Muslims Profess More Private Religious Devotion, Less Public Religious Assertiveness

NOVEMBER 14, 2019 | BY DALIA MOGAHED AND AZKA MAHMOOD

DOWNLOADS

MORE ANALYSES

Not Immune: Some Muslims in America Internalize Islamophobia

Unwanted Sexual Advances from Faith Leaders Are Equally Prevalent Across Faith Groups

The Majority of Muslims Believe Poverty Is the Result of Bad Circumstances, Not Bad Character

To Have and to Hold, Part Two: Interracial Marriage among American Muslims

Muslims Profess More Private Religious Devotion, Less Public Religious Assertiveness

NOVEMBER 14, 2019 | BY DALIA MOGAHED AND AZKA MAHMOOD

Analyzing “how religious” an individual is involves looking at a broad spectrum of acts of faith. This ISPU analysis looks at a series of questions related to public and private practice of faith. Those include: Does private religious devotion always lead to taking visible public religious stances to defend the faith? Does one need to be religious to assert a public faith-based identity? Which major American faith group is most likely to profess deep religious belief but struggle to speak out to defend their faith? The following analysis answers these questions by looking at personal practice, religion in public life, and more.

Personal Practice

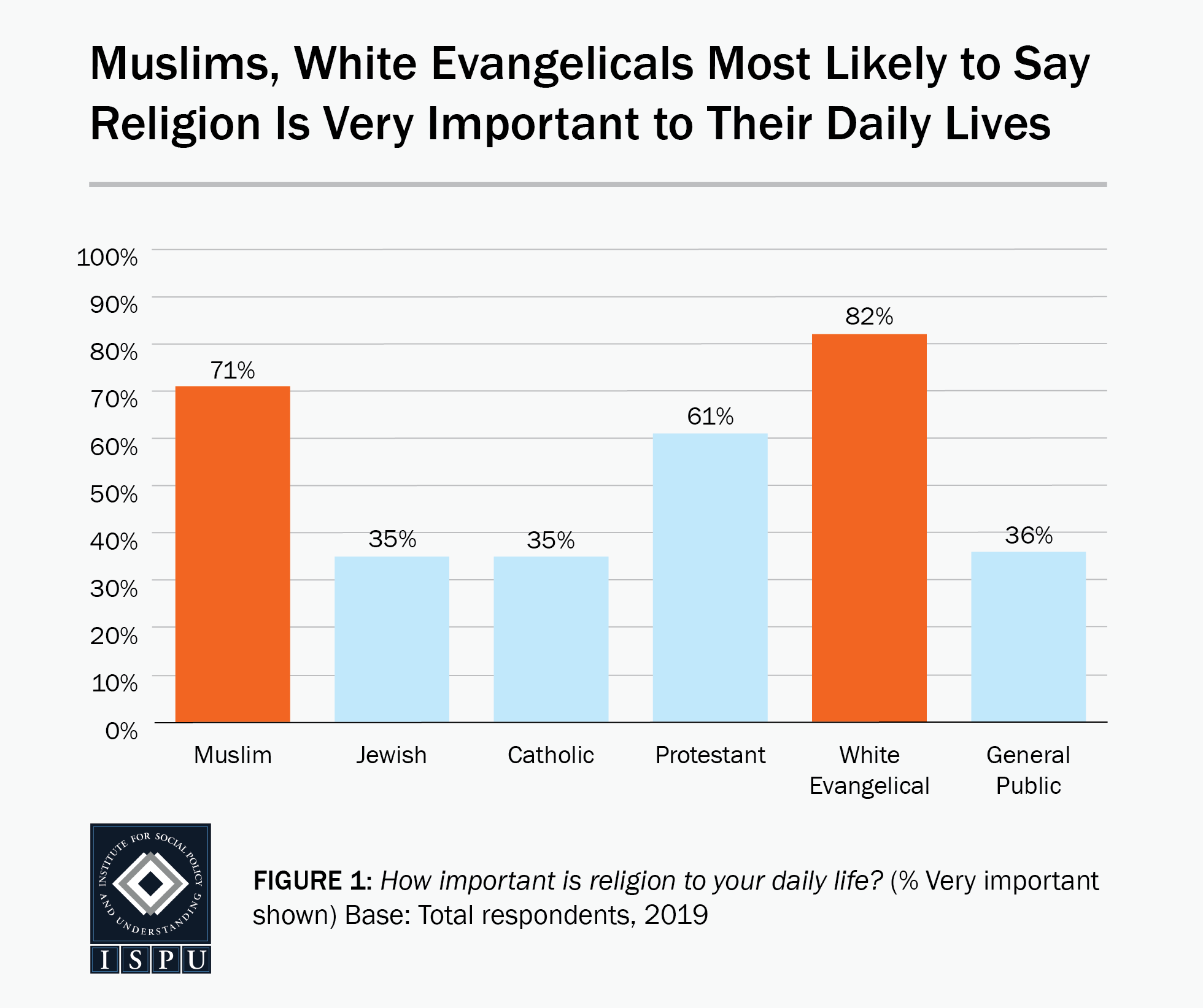

Muslims More Likely to Hold Religion Very Important Than All Other Groups, Except White Evangelicals

Muslims (71%) are far more likely to say religion is “very important to their daily lives” than Jews and Catholics (both 35%), Protestants (61%), or the general public (36%). The importance of faith to Muslims is only surpassed by white Evangelicals (82%) in our survey. Noticeably, though white Evangelicals and Muslims diverge in their views in most of our findings, the two groups stand out as the most devoted to their faith amid a sea of growing secularism (Figure 1).

Muslim women and men are equally likely to say religion is important to them, despite the greater social cost that Muslim women incur for their faith identity in the form of a greater frequency of reported religious discrimination (55% of men vs. 68% of women). Though Muslim women continue to experience greater religious discrimination than all other groups studied—findings that remain the same in 2019 as in previous years—it has not distanced them from their faith.

The percentage of Muslims who report religion as very important to their daily lives has held steady since 2016.

Muslims as Likely to Attend Religious Services as Protestants

As with previous studies (ISPU poll 2016–2018, Gallup 2009, Pew 2011 and 2016), Muslims are on par with Protestants in religious attendance—43% of Muslims and 49% of Protestants report attending a religious service once a week or more. In our survey, Muslim and Protestant religious attendance is greater than Jewish (23%) and Catholic (27%) attendance, but less than that of white Evangelicals (64%).

Uniquely among Muslims, religious service attendance does not differ by age. In the general public, those aged 50 and over are more likely to attend religious services once a week or more frequently than those in younger age brackets. As such, Muslim 18 to 29-year-olds (31%) are more likely to attend weekly religious services than their peers in the general public (18%). Muslim women are less likely than men to attend a weekly service (29% vs. 55%), explained partially by the fact that traditional Islamic teachings require men to attend Friday congregational prayer and make it optional for women.

It is worth noting that Muslim men and women are equally likely to say they are “satisfied with the way things are done at their house of worship” (78% of men and 79% of women). Overall, Muslims (78%) report being more satisfied with the way their houses of worship are run, as compared to Catholics (63%) and the general public (62%).

Muslims aged 50 and older are more likely to be satisfied (89%) with their house of worship than young adult (18–29) and middle-aged (30–49) Muslims (both 76%). It is noteworthy that young adult (52%) and middle-aged Americans (60%) in the general public are also less likely to express satisfaction with their places of worship than their elders ages 50+ (68%). Opinions among Muslims are similar across race.

Personal Spirituality

Spiritual Devotion and Public Religious Assertiveness Don’t Always Align

We aimed to measure not only outward religious practice, but the degree to which faith animated one’s inner reality. We designed a section of our survey to gauge private and public spiritual engagement. Two survey questions intended to measure private religious engagement and three captured public religiosity.

We asked survey participants to indicate how much they agreed or disagreed with the following statement:

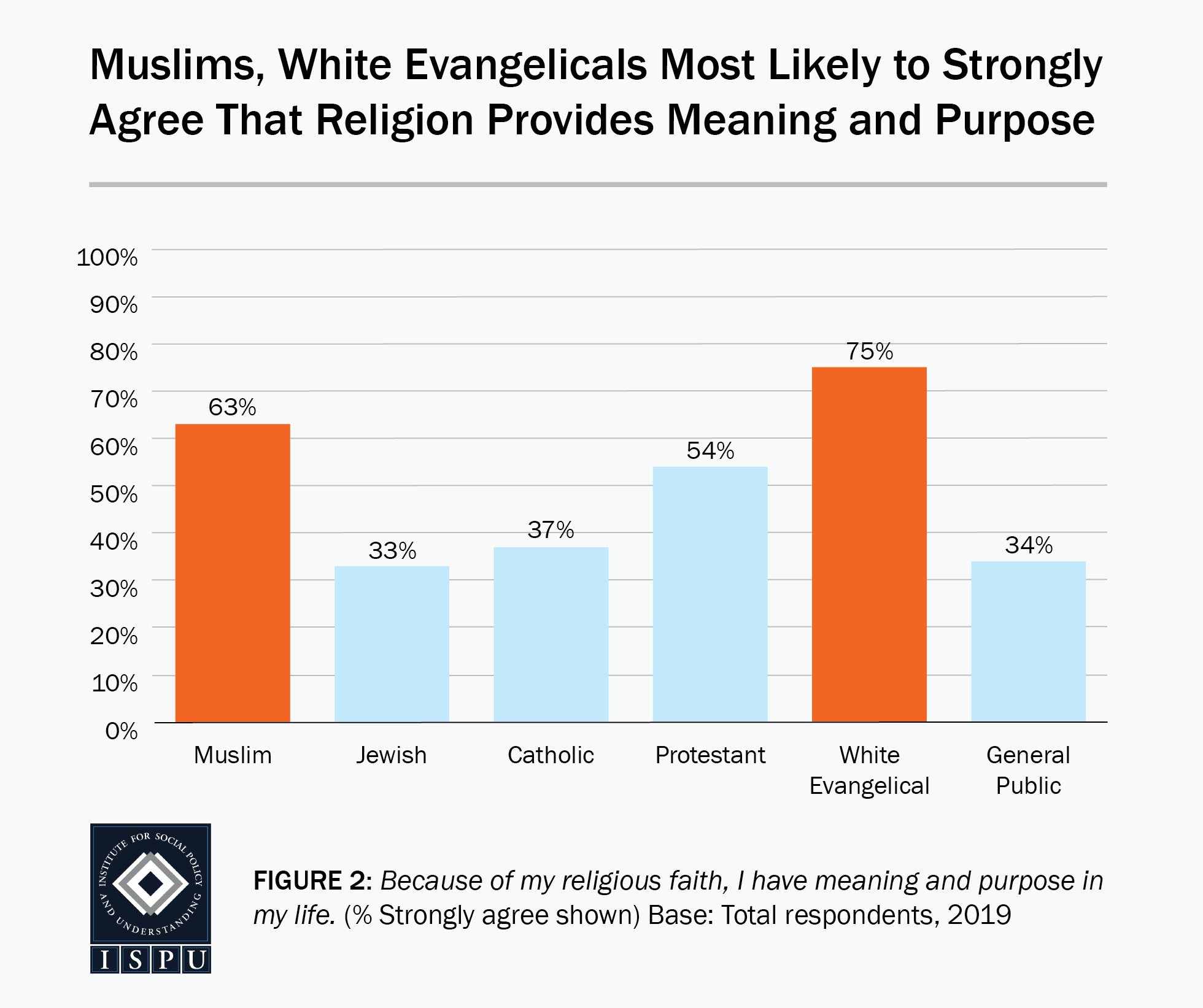

“Because of my religious faith, I have meaning and purpose in my life.”

This question is a measure of the meaning one draws from their religion. We expected this dimension of personal spirituality to closely track with the importance of religion reported by groups overall, and it does. Once again, Muslims (63%) are more likely than Jews (33%), Catholics (37%), Protestants (54%), and the non-affiliated (6%) to strongly agree with the statement. However, white Evangelicals are the group most likely to strongly agree (75%) (Figure 2).

Among Muslims, all ages and races are equally likely to find meaning and purpose through religion. In contrast, in the general public, those aged 50 and older as well as Black Americans are more likely to report the same.

Respondents also reported how strongly they agreed or disagreed with the following statement:

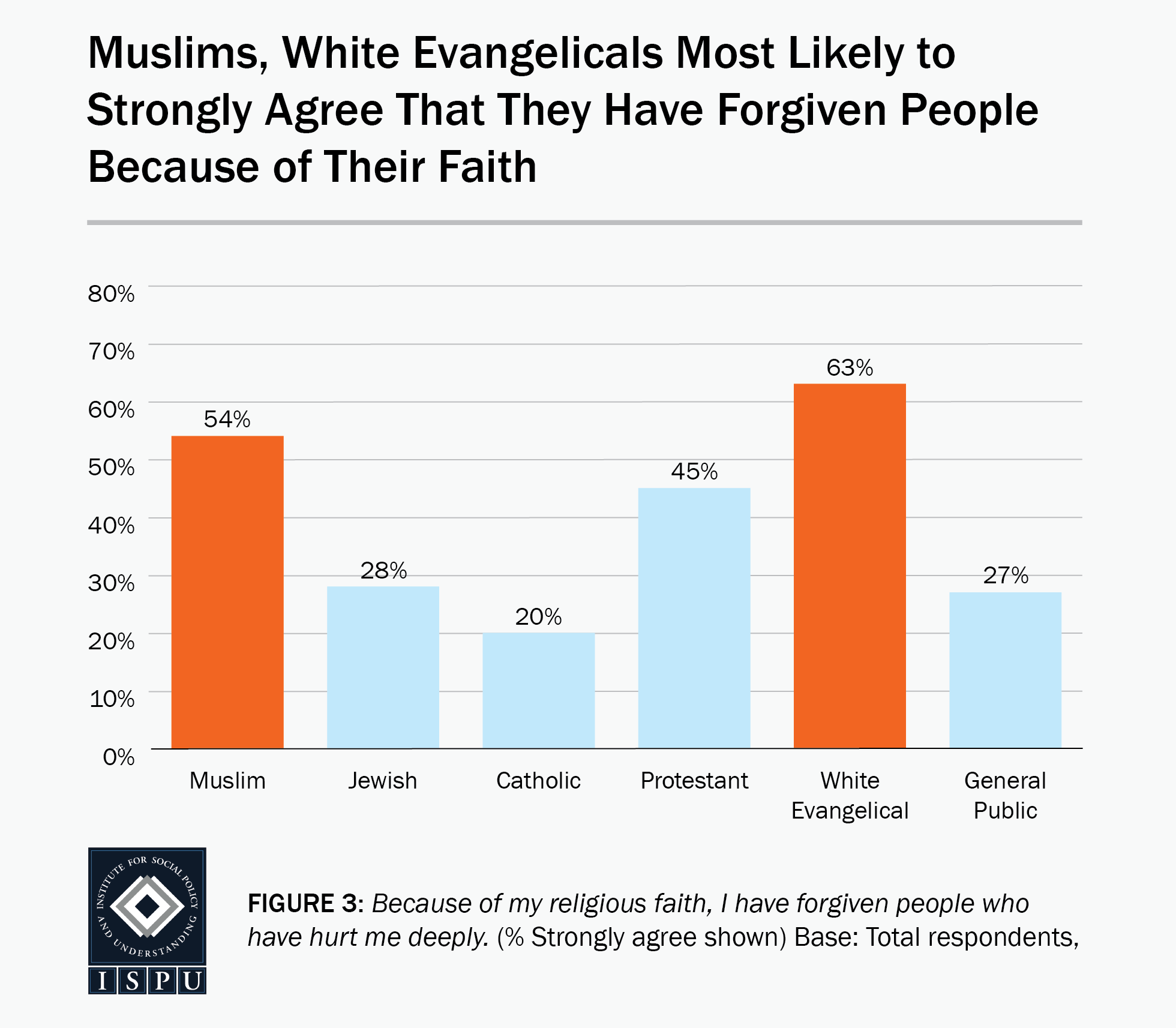

“Because of my religious faith, I have forgiven people who have hurt me deeply.”

This question is a measure of the power of faith to overcome vengeance and ego. We found that Muslims (54%) and white Evangelicals (63%) are most likely to “strongly agree” that they have forgiven someone who has hurt them deeply because of their faith, countering the popular trope that Islam teaches vengeance and Christianity teaches forgiveness (Figure 3).

Religion in Public Life

Respondents were asked to choose one of the following statements that is closest to their point of view:

- Your religion should be the MAIN source of American law.

- Your religion should be a source of American law but not the only source.

- Your religion should NOT be a source of American law.

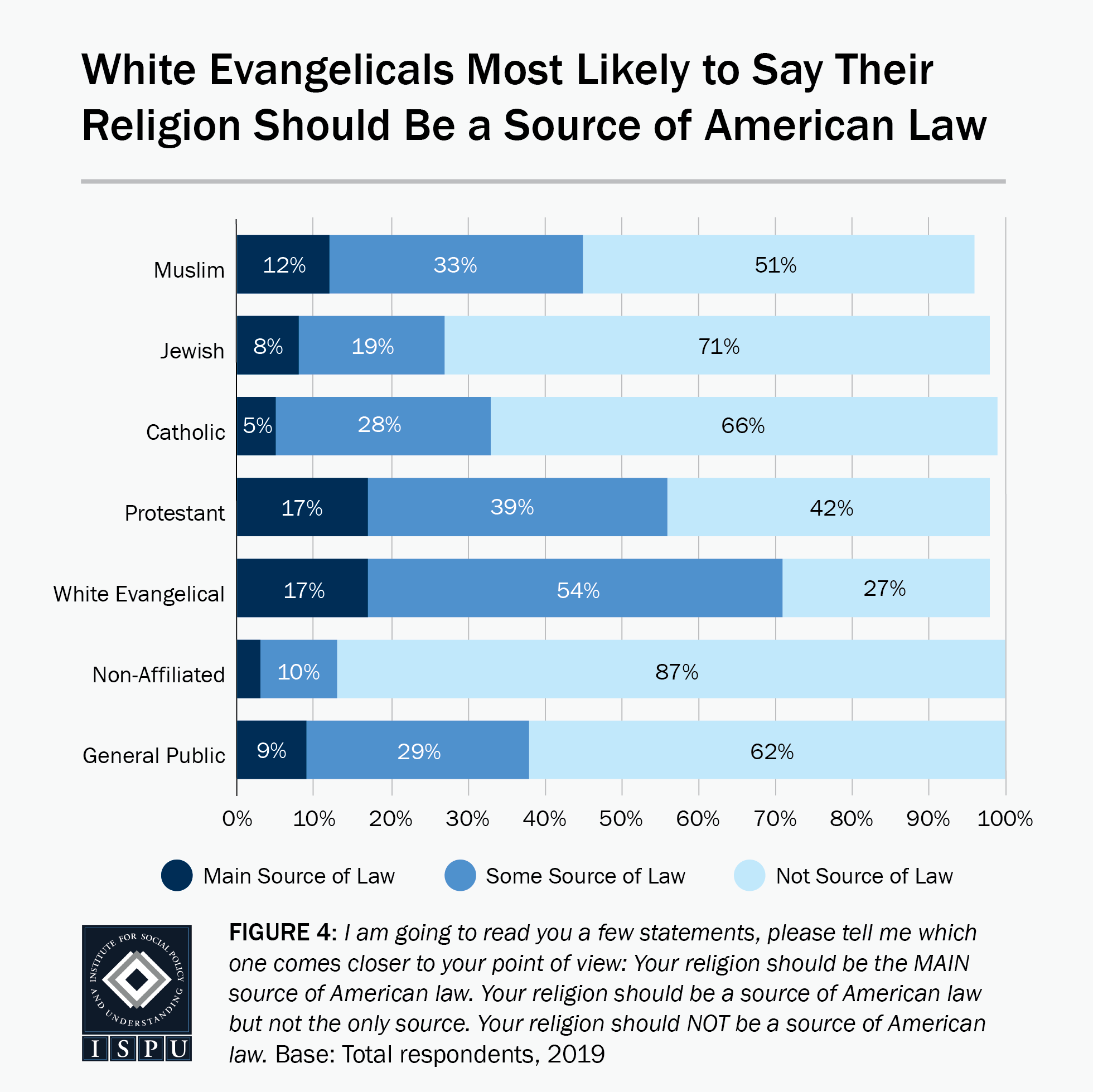

Muslims (33%) are less likely than white Evangelicals (54%) to say they want their religion to be a source of American law but not the only source. Muslims are on par with Catholics (28%), Protestants (39%), and the general public (29%) to hold this view. All these groups are more likely than Jews (19%) and non-affiliated Americans (10%) to agree (Figure 4).

This finding confirms our hypothesis that a group’s wish to link religion to law would mirror the importance of religion to them. These data suggest that people who see their faith as an important part of their personal life also want to see their values reflected in the laws of the land. Muslims are not unique in this regard, nor are they the group most prone to this view.

Within the Muslim community, those who self-identify as Arab (70%) are most likely to see no role for their faith in American law, while other age and racial groups do not differ in their responses. Among the general public, Black Americans (25%) are the most likely to see a role for their faith as the main source of American law.

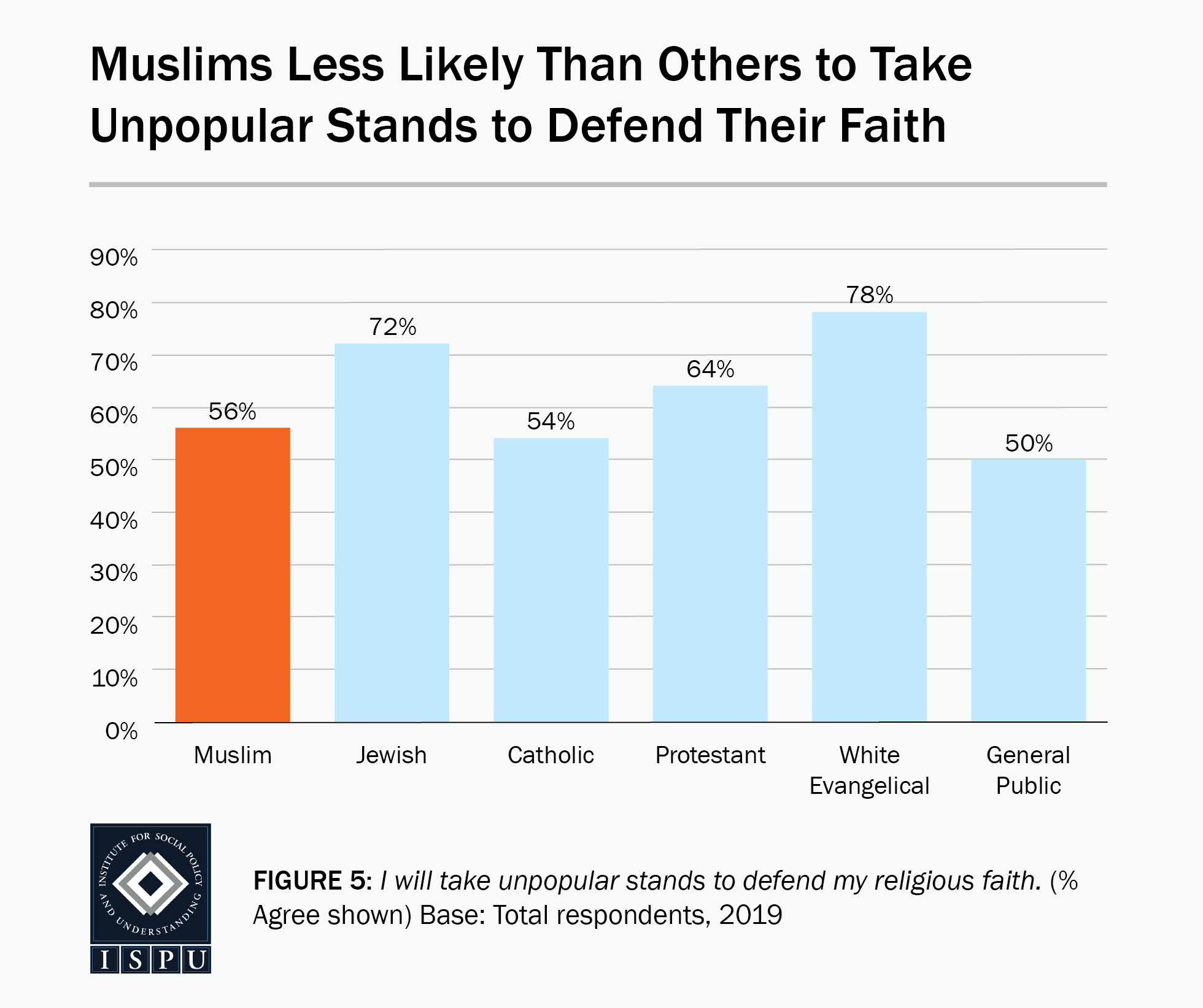

We asked participants to share how much they agreed or disagreed with the following statement:

“I will take unpopular stands to defend my religious faith.”

This question illustrates one’s readiness, or courage, to take a risk to defend their faith by being “unpopular.” We would expect those who see their faith as important to them to be more likely to express this readiness than others who have a more secular outlook. Some groups surprised us. We found that Muslims (56%) are less likely than Jews (72%) to agree that they will “take unpopular stands to defend their religious faith” despite faith being more important to Muslims than it is to Jews according to the data that measure private devotion (Figure 5).

In this instance, Muslims are closer to Catholics (54%) on the spectrum, though they surpass Catholics in the importance of religion in their lives (71% vs. 35% very important) and frequency of religious services (43% vs. 27% once a week or more).

Unsurprisingly, given the importance of religion to their group, roughly three-quarters of white Evangelicals (78%) agree with taking unpopular stands in defense of their faith. This is on par with Jews (72%) despite the sharp difference in their reported private religious devotion.

One reason that can be ascribed to Muslims’ lukewarm support for outspoken displays in defense of their faith is the high incidence of religious discrimination. As a faith group, Muslims report the most frequent religious discrimination (62% vs. 43% or less) and as such have the most to risk with unpopular public displays in defense of their faith.

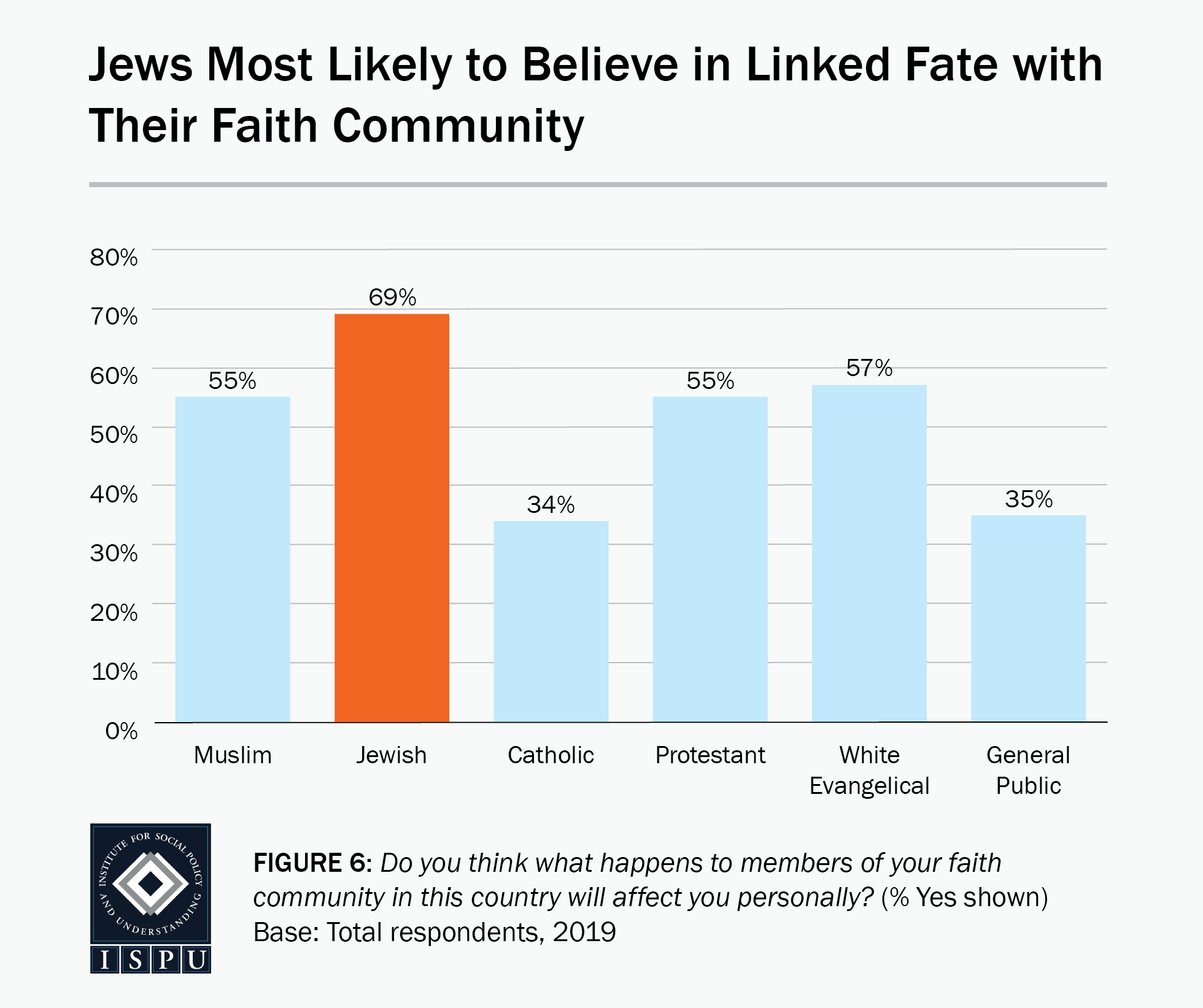

Finally, we asked survey participants the following question:

“Do you think what happens to members of your faith community in this country will affect you personally?”

This question measures what is termed “linked fate” [1], or, how much one feels that their personal lives are impacted by the fate of their religious community. How much solidarity or shared destiny do respondents perceive with their group of co-faithful? The answers would gauge a sense of group cohesiveness, where one’s outcomes are closely linked to those of one’s groups. For instance, those with high levels of “linked fate” would indicate that they are doing well personally if their group is doing well, and they would likewise perceive an attack on the group as being a personal threat.

Our data finds that Muslims (55%) are more likely than Catholics (34%) or the general public (35%) to believe in linked fate, similar to Protestants (55%) and white Evangelicals (57%). Though less pronounced in their religious devotion compared to Muslims and white Evangelicals, Jews (69%) are most likely to express a linked fate with their group. This sense of collective destiny may explain Jews’ willingness to defend their faith in public even if they are not practicing it in their private lives (Figure 6).

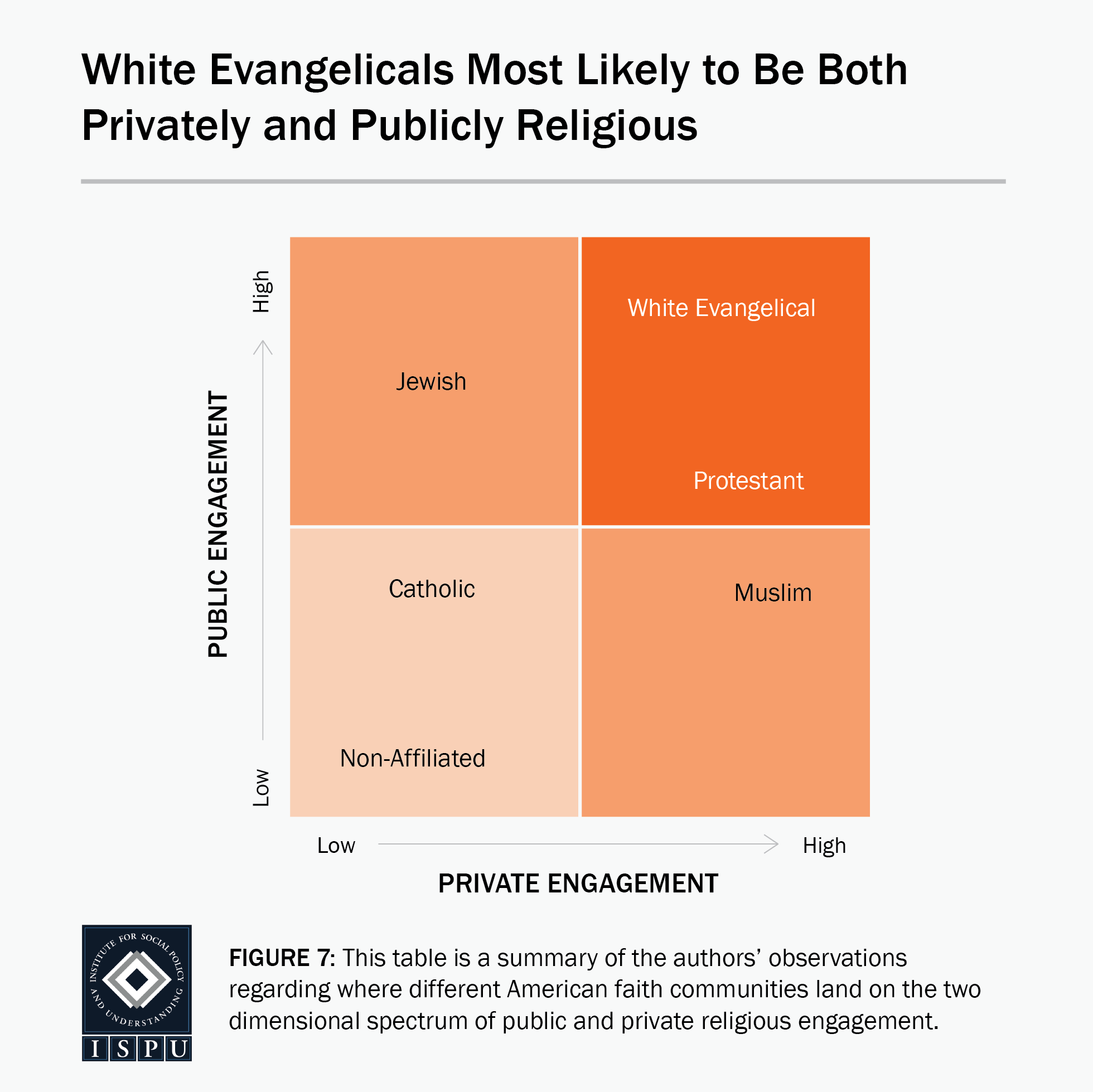

Of the three measures of spiritual engagement—(1) meaning and purpose, (2) forgiveness, and (3) unpopular stances to defend it—Muslims are highest on dimensions that reflect private spirituality and lower on the one that requires public risk. White Evangelicals are high on all three, which reflects their public assertiveness and deep personal devotion. Jews are more likely than Muslims to be willing to take unpopular stances, but lag in the dimensions that reflect personal devotion. Catholics are lower on all three, which corresponds to the less pronounced place religion is reported to have in their personal lives.

Muslims are highest on dimensions that reflect private spirituality and lower on the one that requires public risk.

We have summarized these dimensions in the following framework (Figure 7), placing our surveyed religious communities in one of four quadrants depending on their relative public and private levels of religious engagement.

Protestants and white Evangelicals: At the far upper right-hand side, Protestants and white Evangelicals express strong personal devotion to their faith, consider it an important part of their daily lives, find personal meaning in it, and practice it regularly by attending religious service. They are also more likely to take unpopular stances to defend their faith, see it as a source of legislation, and the majority have a strong sense of “linked fate” with their religious community.

Non-affiliated: At the far lower left-hand corner are non-affiliated Americans, who by definition are low in both membership identity and devotion to a faith, and their responses reflect this.

Catholics: Americans who identify as Catholic are about as likely as Jews, but far less likely than Muslims, Protestants, and especially white Evangelicals to attend a religious service, hold religion important to their daily lives, or derive a strong sense of purpose from their faith. They are also less likely than other Christians to favor taking unpopular stances to defend their faith or to say that their personal fate is intertwined with that of their group. They are more religiously engaged, of course, than non-affiliated Americans, but less so than Muslims and other Christians in their private practice, and less so than Jews and white Evangelicals in their public religious engagement.

Jews: Jews occupy the upper left-hand quadrant: they are lower in their expressed personal or spiritual devotion to their faith, yet more likely than the more religiously devout Muslims and Protestants to be willing to take unpopular stances to defend their faith. Jews are also more likely than Muslims—both religious minorities that face religious discrimination and hate crimes—to see their fate as connected to that of their group. Jews, in fact, share many characteristics of assertive public religious identity with white Evangelicals, but differ in one important dimension of public religious life: their faith as a source of law. Jews are far less likely than white Evangelicals to see a role for their faith in law, and therefore, they are not at the top of the public religious engagement quadrant.

Muslims: Muslims are near the far right-hand end of the private devotion spectrum, but only at the lower middle of the public engagement comparative measure. Muslims are more likely than Catholics, Jews, and non-affiliated Americans to express personal devotion to their faith in their private lives. This applies to the importance of religion to their daily lives, their frequency of attendance of a religious service, and the meaning and purpose they draw from their faith. Muslims are as likely as white Evangelicals to say their faith helped them forgive someone who hurt them deeply, illustrating not just mechanical devotion but the kind that overcomes the ego. And yet, they are as likely as the less personally devoted Catholics, and less likely than the more secular Jews to say they would stand up to defend their faith if the issue were unpopular. Muslims are also less likely than Jews to see their personal fate as connected to their group. However, Muslims surpass Jews on one measure when it comes to public manifestations of faith—their views about seeing their religious values reflected in policy—though Muslims are less likely to hold this view than Protestants and white Evangelicals. Muslims are also the most likely faith community to say they have experienced religious discrimination, and the least likely group studied to enjoy the public’s favorable opinions, which may explain their relative reluctance to take unpopular stances to defend their faith despite its importance to them personally.

This piece is an excerpt from American Muslim Poll 2019: Predicting and Preventing Islamophobia.

Dalia Mogahed is the Director of Research at the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding, where she leads the organization’s pioneering research and thought leadership programs on American Muslims. Mogahed is the co-author of American Muslim Poll 2019: Predicting and Preventing Islamophobia. Learn more about Dalia→

Azka Mahmood is an ISPU Educator who has organized and facilitated educational workshops for journalists and educators across the U.S. Mahmood is the co-author of American Muslim Poll 2019: Predicting and Preventing Islamophobia.

[1] Michael Dawson, Behind the Mule: Race and Class in African-American Politics (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994).