HOLYOKE, Mass. (RNS) — Next week, Jews around the world will be celebrating Passover. Regardless of the pandemic, the holiday commemorating the Jews’ escape from Egypt is on its way.

The Passover Seder is associated with social intimacy: long tables bursting with family, friends and guests, finger foods, wine, conversation, songs and merriment.

In a time of social distancing, how do we conduct our Seders to include our loved ones and our communities?

And what aspects of the Haggadah, the ritual guide to the Seder, can help us make sense of our world today?

RELATED: Click here for complete coverage of COVID-19 on RNS

The Seder plate holds all the ritual foods for the Seder. Image from “The Promise of the Land: A Passover Haggadah” by Rabbi Ellen Bernstein. Art by Galia Goodman

Let’s start with the second question.

The primary theme of the Passover Haggadah is freedom. But the freedom of the Haggadah is not just the freedom from slavery brought to us by a transcendent God. Our freedom rests on the vitality of the living Earth: the air, the water, the microbes. If the Earth and its systems are out of whack, our freedom is compromised. Life itself is compromised.

The coronavirus is teaching us — the hard way — many of the ecological lessons that we’ve needed to learn for decades: We live in intimate connection with each other and the whole world. Our actions have consequences. We are learning that an act as simple as a sneeze can have devastating results.

We are learning to live more simply. Nothing teaches us the value of simplicity as much as matzo, the unleavened bread that is the primary symbol of Passover. Made of the most basic ingredients, wheat and water, matzo teaches us that the freedom we know on Passover comes when we rid ourselves of the burden of excess.

We are learning about humility. Yachatz, the moment in the seder where we break the matzo, affords us the opportunity to contemplate our own brokenness. Never was Yachatz more poignant. Who isn’t feeling some sense of brokenness right now?

And we are learning about — no — we are experiencing the plagues. This year we need no commentary to understand the meaning of the plagues. Our recitation of the plagues becomes a mournful lament — a prayer for healing.

In these times, it’s so important to recognize our blessings amid the grim reports. Passover comes to remind us to bless, just when we need it most. We offer up blessings for the wine, for the first greens of spring, for washing our hands. (The significance of the Jewish custom of double-hand-washing is particularly suggestive today.) We offer a blessing for the matzo and one for maror, the bitter herb, the bitterness.

How will we bless the bitterness this year?

The goat is one animal often associated with the Seder. Image from “The Promise of the Land: A Passover Haggadah” by Rabbi Ellen Bernstein. Art by Galia Goodman

Undergirding the Seder’s celebration of freedom is this sense of gratitude. “Dayeinu,” meaning “it would have been enough,” refers to each individual gift we have received from God, an expression of radical appreciation. Dayeinu teaches that when we take a moment to feel satisfied with what we already have, we recognize how blessed we are.

Indeed, with the world on quarantine, just taking a walk and breathing fresh air becomes a cherished activity. We have never known the radiance and richness of the living Earth like we do right now.

Now, to our first question. How to conduct a Seder in this time of physical distancing? Many of us are taking to the internet to bridge the distance and hosting virtual Seders that highlight some of these ideas. We are calling these Earth Seders.

Earth Seders refer to traditional Passover Seders that acknowledge the interconnectedness of our lives with the Earth, its people and creatures. Today Earth Seders have acquired new meaning: Not only are they grounded in the Earth; they welcome people from all corners of the Earth.

We are living in worrisome times. But we are also living in a time of opportunity. People in different parts of the world can co-lead a Seder with far-flung musicians who can lift up the Seder with singing. The internet also allows us to fulfill one of the primary mitzvahs of the Seder: to reach people “in need,” including those who are alone, homebound and ill.

Our history is rich with stories of Jews during the time of the Spanish Inquisition and the Holocaust holding furtive Seders. The certainty of the holiday cycle and Shabbat has always helped to sustain the Jewish people through times of great adversity. The Seder presents a template where we can gain survival tools by retelling our origin story, enacting rituals, singing and learning together.

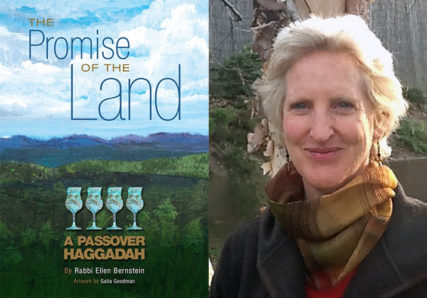

“The Promise of the Land: A Passover Haggadah” and author Rabbi Ellen Bernstein. Courtesy images

On a most essential level, the Passover Seder celebrates the spring and with it new beginnings. May it refresh us with hope and renewal in this time of great uncertainty.

(Rabbi Ellen Bernstein is the founder of Shomrei Adamah, a Jewish environmental organization, and is the author of “The Promise of the Land,” a new ecologically sensitive Passover Haggadah. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)