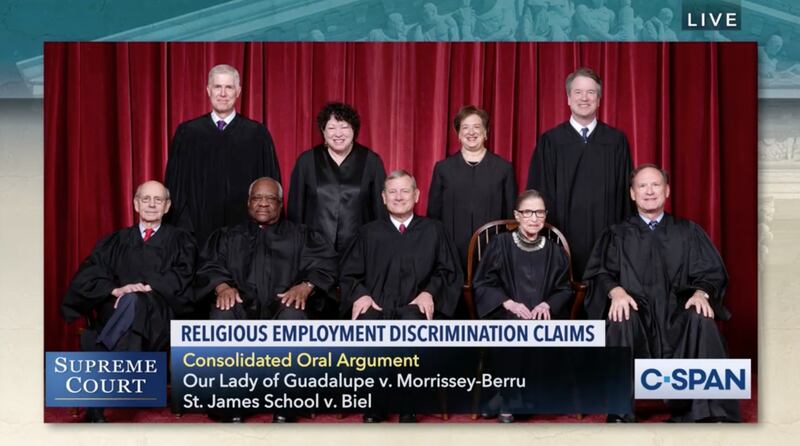

SALT LAKE CITY — After more than 90 minutes of confusing hypothetical scenarios, conflicting claims and several questions about religious freedom, the Supreme Court wrapped up oral arguments Monday in its final religion case this term.

The case, Our Lady of Guadalupe School v. Morrissey-Berru, involves a legal concept called the ministerial exception, which bars the government from weighing in on employment disputes between a religious organization and its ministerial employees.

The justices will clarify who counts as a minister under the law and decide whether two Catholic school teachers should be allowed to move forward with age and health-related discrimination claims.

Attorneys for the schools argue the teachers were assigned enough faith-related duties to fall under the exception and that a ruling that says as much would do little to disrupt the government’s goal of rooting out discrimination.

“Religious bodies get to decide who best performs ... important religious functions,” Eric Rassbach, vice president and senior counsel at the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, told the justices. “Courts really shouldn’t be in the business of second-guessing that.”

But Jeffrey Fisher, who appeared in front of the court Monday on behalf of the teachers, said religious freedom concerns aren’t the only issue for the court to consider. A ruling in favor of the schools could end up harming hundreds of thousands of employees who previously weren’t covered by the ministerial exception, he argued.

“It is truly a sea change that is being requested,” Fisher said.

Defining minister

The justices won’t be starting from scratch when they set out to determine who counts as a minister. The court previously addressed that question in 2012, when they sorted out a conflict between a fourth grade teacher and a Lutheran school.

In that case, the justices unanimously ruled that an employee does not have to be an ordained pastor to be seen as a minister under the law. They instructed lower court judges to consider a variety of factors, including an employee’s title, training and job duties, when deciding whether the ministerial exception should apply.

“Every court of appeals to have considered the question has concluded that the ministerial exception is not limited to the head of a religious congregation, and we agree,” the ruling said.

The schools involved in the current case believe the court’s 2012 formula for figuring out who is a minister needs to be further refined. It should be clear that employees who serve important religious functions can be considered ministers even when they don’t have special titles or training, they said.

The court shouldn’t be asking judges “to decide what titles sound religious enough,” said Rassbach, who argued on behalf of the two Catholic schools.

An overreliance on titles harms religions, like Catholicism, that rarely refer to someone as a minister unless they’ve been ordained, added Morgan Ratner, who is an assistant to the U.S. solicitor general and joined Rassbach to argue for the schools.

“Titles may be relevant” in many cases, she said. But focusing on them too much “creates a real problem in terms of religious neutrality.”

Moving forward, it would be better for courts’ primary focus to be on an employee’s job duties, Ratner said. If an employee spends a significant amount of time teaching, preaching, leading worship or otherwise communicating about faith, then they should be seen as a ministerial employee.

Courts should focus on whether religious activities comprise “a meaningful part of a person’s job,” she said.

Several justices said such an approach wouldn’t be as easy for courts to adopt as it might appear. It seems like it would force courts to make subjective decisions about which activities are religious enough, said Chief Justice John Roberts at one point.

“Is a court supposed to determine what is a significant religious function and what is an insignificant one?” he asked.

Both Rassbach and Ratner said the court already offered a basic definition of significant religious functions in the 2012 case. Judges would just need to consider how much of a role preaching or teaching about religion plays in an employee’s typical work week.

If a teacher is just doing one thing, like offering a brief prayer before class begins, “that probably would fall outside the exception because (religion) is not at the heart of what they’re doing,” Rassbach said.

But, at the end of the day, courts would still have to decide how much religious activity would need to take place for an employee to rise to the level of minister, Justice Sonia Sotomayor said.

“When ... you’re just left with those terms ‘preaching’ and ‘teaching,’ that’s when you get into all the tricky questions like how much preaching? How much teaching?” she said.

When it was his turn to answer questions, Fisher focused on the idea that a job duties-focused approach would be unsustainable for the reasons outlined by Sotomayor and others. He urged the Supreme Court to reaffirm its 2012 ruling and reiterate that religious titles and training matter in ministerial exception cases.

“The solution is to look to objective factors,” he said.

Like Ratner and Rassbach, Fisher faced pushback. For example, Justice Clarence Thomas returned to the idea that looking at titles harms faith groups that don’t use them that much.

The presence of a religious title is just one factor for courts to consider among many, Fisher argued.

“Even in a religion that (rarely uses religious titles), there would be significant religious training in play,” he said.

Civil rights or religious freedom?

In addition to clashing over whether the Supreme Court’s 2012 formula for deciding ministerial exception cases is clear enough, attorneys on both sides of the current dispute disagree on the broader impact of a ruling in favor of the religious schools.

Rassbach and Ratner argue it would simply make cases in which a teacher clearly has many significant religious duties but no special title easier to resolve. Fisher, on the other hand, believes such a ruling would deprive hundreds of thousands of employees of the protections offered under employment discrimination law.

The cause could “blow a hole in our nation’s civil rights laws,” he said.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg appeared inclined to agree. At several points during oral arguments, she wondered if broadening the ministerial exception might make it harder for the government to address issues like sexual abuse or fraud. An employee would hesitate to report a problem if they knew they had no recourse to losing their job, she implied.

In response to one of Ginsburg’s hypotheticals, Ratner encouraged the justices to stay focused on the current case. The Supreme Court has been asked to decide who counts as a ministerial employee, not in what types of discrimination cases the ministerial exception applies, she said.

However, Ginsburg wasn’t the only justice thinking about issues beyond the current case. Several of the court’s more conservative justices seemed to believe that failing to broaden the ministerial exception would send the wrong message about religious freedom.

“Why would we second guess sincerely held religious beliefs” about who counts as a minister?, asked Justice Neil Gorsuch near the end of Monday’s proceedings.

It seems clear that, unlike in 2012, this ministerial exception case won’t end with a unanimous ruling, legal experts said. Unity isn’t easy when the justices have different views on the stakes of the case.

The Supreme Court’s decision is expected sometime this summer.

alt=Kelsey Dallas

alt=Kelsey Dallas