(RNS) — John Lewis, the longtime civil rights activist, congressman and ordained Baptist minister who preached about getting in “good trouble,” died Friday (July 17) at the age of 80.

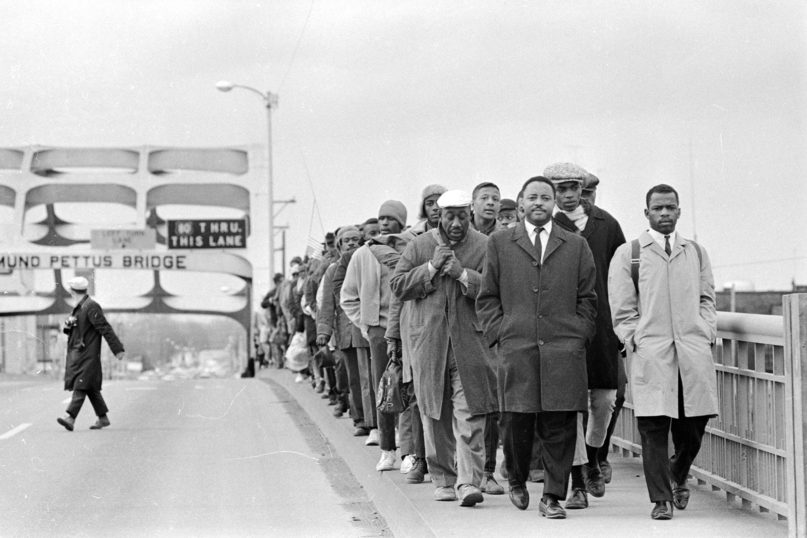

A founding member and former chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, Lewis was among the demonstrators beaten by police after walking across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, in 1965. At 23 years old, he was the youngest speaker at the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, which he helped to organize, stepping to the microphone shortly before the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

The Congressional Black Caucus announced the death of its longtime member in a statement on Friday.

“The world has lost a legend; the civil rights movement has lost an icon, the City of Atlanta has lost one of its most fearless leaders, and the Congressional Black Caucus has lost our longest serving member,” it said.

Lewis, who represented Georgia’s 5th District, which comprises most of Atlanta, had announced in December 2019 that he been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer.

That announcement prompted tweeted prayers from luminaries ranging from the Revs. Al Sharpton and William Barber II to Fox Business News anchor Lou Dobbs and former President Barack Obama.

Hearing of Lewis’ death, Obama said: “He believed that in all of us, there exists the capacity for great courage, a longing to do what’s right, a willingness to love all people, and to extend to them their God-given rights to dignity and respect. And it’s because he saw the best in all of us that he will continue, even in his passing, to serve as a beacon in that long journey towards a more perfect union.”

From childhood, when Lewis preached to chickens on his family farm, to his twilight years, when he urged the attendees of the 2020 National Prayer Breakfast to “be a blessing to our fellow human beings,” faith was the fuel of Lewis’ life.

“As a people of faith, as a people of hope, we need the blessing of God Almighty,” he prayed as he uttered a benediction for the breakfast via videotape in February, with a photo of the U.S. Capitol as a backdrop.

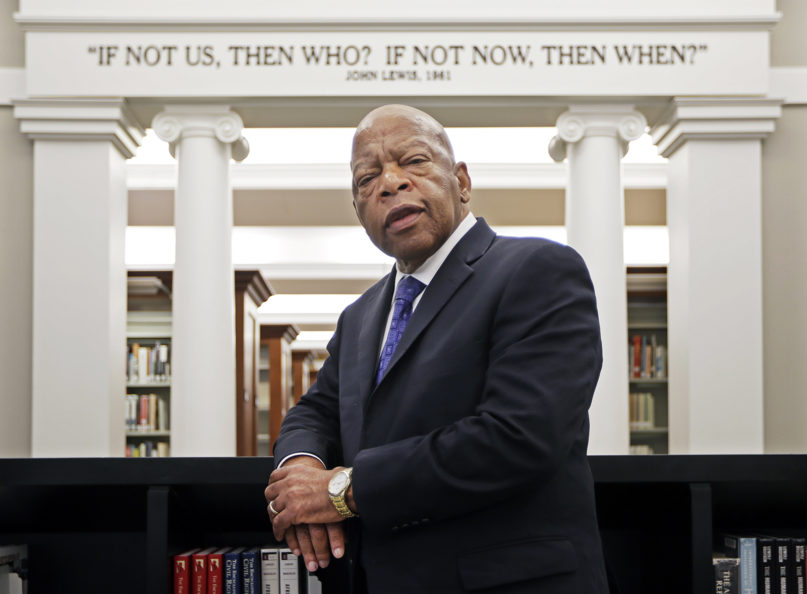

Civil rights veteran and Congressman John Lewis urged black clergy to work for changes in the Voting Rights Act on June 25, 2015, at the Rayburn House Office Building. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

“It does not matter what language you speak or the color of your skin, it does not matter whether you worship one God, many gods or no gods. We are one people, one family.”

Lewis recounted his young days of ministry in “March,” the award-winning graphic novel series about his life in rural Alabama, his role in interfaith and interracial civil rights marches and his leadership as a Democratic congressman.

Born near Troy, Alabama, in 1940, he preached his first public sermon five days before he turned 16, on the theme “A Praying Mother,” based on the Bible’s First Book of Samuel. A nearby newspaper wrote about it, featuring his photo: “That was the first time I ever saw my name in print,” he wrote in the first book of the trilogy of graphic novels, written with Andrew Aydin and illustrated by Nate Powell.

RELATED: John Lewis, ‘March’ team talk about faith and civil rights

Lewis attended segregated schools, often hiding under his family’s front porch and running to catch the bus to escape the grueling tasks of planting and harvesting crops in favor of getting an education. As he grew up, sometimes carrying his Bible to school, the future congressman was influenced by the faith and activism of laypeople such as Rosa Parks and clergy such as King, whom he first met in 1958.

Lewis graduated from American Baptist Theological Seminary (now American Baptist College) in Nashville, Tennessee, and later earned a bachelor’s degree in religion and philosophy from Fisk University.

In his book “Across That Bridge: A Vision for Change and the Future of America,” Lewis included a chapter on faith. In it, he talked about living out principles of compassion and unity, concepts he said were shared by a range of faith groups, including Christians, Jews, Muslims, Hindus and others.

John Lewis, far right, crosses the Edmund Pettus Bridge with fellow protesters in March 1965. © Alabama Department of Archives and History. Donated by Alabama Media Group. Photo by Tom Lankford, Birmingham News. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

“It was no accident that the movement was led primarily by ministers — not politicians, presidents or even community activists — but ministers first, who believed they were called to the work of civil rights as an expression of their faith,” he wrote in the book. “Religious faith is a powerful connecting force for any group of people who are working toward social change.”

The Rev. Howard-John Wesley, senior pastor of Alfred Street Baptist Church in Alexandria, Virginia, noted that Lewis was among the key men and women who accompanied King and made sacrifices for benefits Wesley and others in the next generation now reap.

“John Lewis is clearly one of those — an inspiration to me to be reminded that the true legacy of any person is not what they achieve or acquire, but what they do for others,” said Wesley, who was a Martin Luther King Jr. scholar at Boston University’s theology school. “That’s why we loved him so much. That’s why we mourn him.”

In 1961, Lewis applied to be a Freedom Rider, a member of a corps of civil rights workers who sought to desegregate buses in the South.

In the 2020 documentary “John Lewis: Good Trouble,” the native of rural Alabama recalled how he ate Chinese food for the first time at a Washington restaurant just before embarking on his first Freedom Ride.

“Someone that evening said, ‘You should eat well because this might be like the Last Supper,’” he recalled.

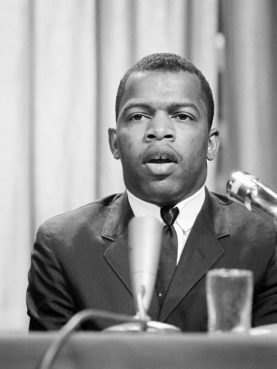

American civil rights activist John Lewis on April 16, 1964. Photo by Marion S. Trikosko/LOC/Creative Commons

Lewis was arrested dozens of times — 40 instances in the 1960s alone — and faced angry and violent opponents.

He told the crowd of hundreds of thousands at the March on Washington, “By the forces of our demands, our determination, and our numbers, we shall splinter the segregated South into a thousand pieces and put them together in the image of God and democracy.

“We must say: ‘Wake up America! Wake up!’ For we cannot stop, and we will not and cannot be patient.”

He was appointed by President Jimmy Carter in the 1970s to lead a national volunteer program. In 1981, he was elected to the Atlanta City Council and served as a member of Congress since his 1986 election.

As the country marked the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington in 2013, Lewis told Religion News Service that his enduring recollection of that day was the religious unity demonstrated by the people in attendance.

“My most lasting memory of my participation in the march was to march with Martin Luther King Jr., Rabbi Joachim Prinz, Eugene Carson Blake of the National Council of Churches and the World Council of Churches,” he said, “and to see hundreds of thousands of people carrying signs representing different religious communities from all over America.”

Lewis made an annual pilgrimage with the Faith and Politics Institute to the bridge and other historic civil rights sites in Alabama with a bipartisan group of politicians and faith leaders. On March 1, just months after his cancer diagnosis, he made an unexpected appearance at the commemoration of “Bloody Sunday” in Selma, 55 years after the Pettus Bridge march.

“We were beaten, we were tear-gassed. I thought I was going to die on this bridge,” he said in a tweet that day. “But somehow and some way, God almighty helped me here. We cannot give up now. We cannot give in. We must keep the faith, keep our eyes on the prize.”

In recent years, Lewis has continued to preach his message about the need to enhance voting rights.

RELATED: Civil rights veteran John Lewis urges black clergy to ‘fix’ Voting Rights Act

In a 2013 ruling, the Supreme Court invalidated a key provision of the Voting Rights Act, ending rules that would spur a mandatory Justice Department review of new voting regulations in states with a history of voting discrimination. The high court’s action was considered by opponents to be a “gutting” of the landmark legislation that Lewis had taken blows to put in place.

He spent the ensuing years urging members of Congress and clergy to work for revisions that would restore the provision that had been struck down.

In this Feb. 15, 2011, file photo, President Barack Obama presents a 2010 Presidential Medal of Freedom to U.S. Rep. John Lewis, D-Ga., during a ceremony in the East Room of the White House in Washington. Lewis, who carried the struggle against racial discrimination from Southern battlegrounds of the 1960s to the halls of Congress, died Friday, July 17, 2020. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster, File)

“We need to fix it before next year’s election. We’ve got to do it, brothers and sisters,” Lewis told leaders of the Progressive National Baptist Convention in 2015. “We have a moral obligation, a mission and a mandate to do it.”

Gavel in hand, Lewis announced in December the House’s passage of a bill to restore the provision, but the measure has not moved forward since being referred to the Senate Judiciary Committee.

He also encouraged others to keep working on the goals put forth by King, who spoke of the “three evils” of racism, poverty and militarism.

Barber, co-chair of the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival, which echoes a similar effort by King, said that Lewis supported the newer version of the campaign.

“It was on that Edmund Pettus Bridge that John Lewis gave his blessing and encouraged us,” Barber said in a June conference call with faith leaders. “And when I talk to him from time to time, he always says, ‘Stay with it.’”

Lewis was honored by Obama with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in a 2011 ceremony and a month later at the 125th anniversary of his home church, Ebenezer Baptist Church, where King was co-pastor in the 1960s.

Five years after receiving the honors from the White House and his church, Lewis spoke at a 2016 community forum at Ebenezer on gun violence. It occurred a week after he led a sit-in on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives to draw attention to the issue.

“Sometimes you have to find a way to get in the way,” he said, reciting his mantra to hundreds of people the church. “Sometimes you have to find a way to make a way out of no way. Sometimes you have to find a way to get in trouble, good trouble, necessary trouble and that’s what we did.”

Asked in 2016 if he ever regretted not sticking with ministry in its traditional sense, Lewis told RNS he did not at all.

“I think my pulpit today is a much larger pulpit,” he said. “If I had stayed in a traditional church, I would have been limited to four walls and probably in some place in Alabama or in Nashville, Tennessee. I preach every day. Every day, I’m preaching a sermon, telling people to get off their butts and do something.”