Does Biblical Literacy Enrich Constitutional Literacy?

The Bible’s Forgotten Influence on the American Constitutional Tradition

Daniel L. Dreisbach

This article is part of our “Law, Religion, and the Constitutionalism” series.

If you’d like to check out other articles in this series, click here.

The American Constitution drew on diverse intellectual traditions.1Portions of this article were adapted from Daniel L. Dreisbach, Reading the Bible with the Founding Fathers (2017). All biblical quotations in the article are taken from the Authorized (King James) Version of the Bible because this is the English language translation most widely used in the American founding era. Among the influences constitutional scholars and political theorists have identified and studied are English common law and British constitutionalism, Enlightenment liberalism in manifold forms, and various experiments in and expressions of republicanism.

Another important, yet often overlooked, influence is a biblical tradition, both Hebraic and Christian. The Bible’s stamp on the American constitutional tradition, from which emerged the national charter crafted in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787, is not surprising, given the expansive influence of Christianity and its sacred text on the culture. A Christian identity and mission were woven into the legal and political cultures of many of Britain’s North American colonies. New England Puritans, in particular, set out to establish Bible commonwealths based in part on biblical law as interpreted through their peculiar theological lens. In colonies both north and south, the Bible was a prodigious source of laws.

The claim that Christianity or the Bible influenced the American Constitution will strike some as provocative, if not wrongheaded, insofar as it challenges a prevalent view in popular culture and the academy. The conventional position is that the Constitution is a strictly secular document — a new document for a new secular order committed to the separation of church and state. It is often said that the American founding in the last third of the eighteenth-century, sandwiched between two great religious revivals, was an Age of Enlightenment, when rationalism was in the ascendency and revelation was, if not rejected outright, relegated to the sidelines.2See, for example, Wilson Carey McWilliams, The Bible in the American Political Tradition, in Religion and Politics, 21 (Myron J. Aronoff, ed. 1984) (“the founding generation rejected or deemphasized the Bible and biblical rhetoric”). The infrequent references to the Bible or explicitly Christian thinkers during substantive debates reported in the surviving records of the Constitutional Convention would seem to support this view.

A Christian identity and mission were woven into the legal and political cultures of many of Britain’s North American colonies. . . In colonies both north and south, the Bible was a prodigious source of laws.

Contemporary scholarship brims with commentary dismissive of Christian or biblical influences on the American founding in general and the Constitution in particular. William Martin, for example, an acclaimed student of religion in America, remarked: “In keeping with their determination to separate religion and government, the framers wrote a constitution that was entirely secular. . . . The Founding Fathers were cosmopolitan intellectuals devoted to the rationalism of the Enlightenment.”3William Martin, With God on Our Side: The Rise of the Religious Right in America 375, 376 (1996). In this same vein, historian Steven J. Keillor asserted: “A ‘remarkably secular’ Convention produced ‘a perfectly secular text’. . . . [C]ompared to state constitutions, it was irreligious: it was a product of the irreligious Enlightenment.”4Steven J. Keillor, This Rebellious House: American History & the Truth of Christianity 96-97 (1996). University of Pennsylvania law professor Kermit Roosevelt reportedly commented: “I’m not sure it’s historically accurate to say the founders drew their thoughts from the Bible. I don’t think the U.S. Constitution reflects Christian ideals or doctrine. The Bible is not useful to interpret the Constitution.”5Alfred Lubrano, $60 million Bible center planned for Independence Mall, Phil. Inquirer, Jan 12, 2017. These are a few illustrations of a sentiment popular in the academy.6For more examples, see Mark David Hall, Did America Have a Christian Founding?: Separating Modern Myth from Historical Truth (2019).

Notwithstanding this familiar refrain, I contend that biblical ideas, disseminated through diverse channels, contributed to an American constitutional tradition committed to, among other things, limited government, rule of law, due process of law, separation of powers, checks and balances, republican self-government, liberty of conscience, and the right of the people to resist tyrannical rule. Evidence buttressing this claim is found in the milieu from which emerged American constitutions; the legal, political, and religious ideas known to have informed the constitutional framers’ views on law and civil government; and constitutional design and surviving records of constitutional deliberations. Prominent among these influences on the framers were English common law and Protestant Reformed theology.

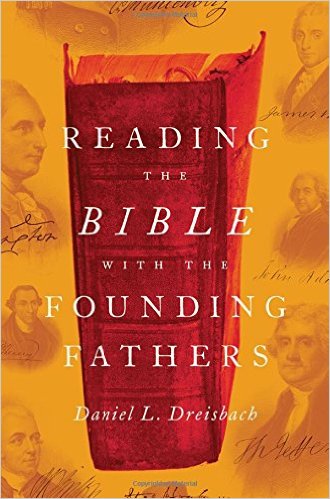

As I emphasize in my book, Reading the Bible with the Founding Fathers (2017), the Bible was not the sole source of the ideas that animated the nation’s founding. The founding generation, as already acknowledged, drew on and synthesized diverse traditions in forming their political and constitutional thought. Furthermore, I do not suggest that every constitutional idea or concept said to reflect biblical influence is, in fact, original to a biblical tradition or that there are no similar expressions of these ideas outside a biblical tradition. Many of the provisions identified below, said to reflect biblical influence, find the same or equivalent expression in other legal traditions. Rather, I suggest that the Bible and Christianity were channels through which many Americans learned about and came to embrace civic ideas they identified with Christianity, even though these or similar ideas found parallel expression in traditions separate from Christianity and its sacred writings. This is not surprising, given that the Bible was arguably the most accessible, familiar, and authoritative text in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century America, and many pious Americans gave great credence to ideas they believed were derived from or compatible with Scripture, reassured that such ideas enjoyed divine favor. There were, of course, learned Americans in the founding era who studied legal and political concepts that they knew were manifested similarly in both Christian teachings and other traditions.

Drawing attention to the Bible’s contributions to the founding is not meant to diminish, much less dismiss, other intellectual influences on the founders. Rather, acknowledging the Bible’s often ignored role in the founding enriches our understanding of the broad range of ideas that inspired and informed the founding generations’ political thoughts and shaped their constitutional experiments at the end of the eighteenth-century.

Furthermore, the claim that the Bible influenced the American constitutional tradition is not a claim that this constitutional tradition or the U.S. Constitution formally and legally established biblical Christianity or even gave preference to Christianity in law or policy. It merely acknowledges that the Bible was among the mix of sources that informed American constitutionalism.

The Bible in the Political Culture of the American Founding

The founders read the Bible. Their many quotations from and allusions to both familiar and obscure scriptural texts confirm that they knew the Bible from cover to cover. Biblical language and themes liberally seasoned their political rhetoric. The phrases and cadences of the King James Bible, especially, informed their written and spoken words. Its ideas shaped their habits of mind and informed their political pursuits.

The Bible was an accessible and authoritative text for most eighteenth-century Americans; and effective communicators, especially politicians and polemicists, adeptly used it to reach their audiences. The mere fact that a founder quoted the Bible, however, does not indicate whether that individual was a believer or a skeptic. Both, including some who doubted the Bible’s divine origins, appealed frequently to Scripture in their political discourse.

In an often-cited study published in the American Political Science Review on the sources referenced in the political literature of the American founding, political scientist Donald S. Lutz reported that the Bible was cited more frequently than any European writer or even any European school of thought, such as Enlightenment liberalism. The Bible, he found, accounted for approximately one-third of the citations in the literature he surveyed. The book of Deuteronomy alone was the most frequently cited work, followed by Baron de Montesquieu’s The Spirit of the Laws (1748). In fact, Deuteronomy was referenced nearly twice as often as all of John Locke’s writings put together, and “Saint Paul [was] cited about as frequently as Montesquieu and [William] Blackstone, the two most-cited secular authors.”7Donald S. Lutz, The Relative Influence of European Writers on Late Eighteenth-Century American Political Thought, 78 Am. Pol. Sci. Rev. (March 1984) 189-197; Lutz, The Origins of American Constitutionalism 140 (1988); Lutz, A Preface to American Political Theory 136 ( 1992).

Given the Bible’s pervasive presence in eighteenth-century culture, there is little surprise that the founding generation appealed frequently to biblical language and principles in their political discourse and deliberations. The nineteenth-century historian John Wingate Thornton wrote, the Bible “was the great political text-book of the patriots.”8John Wingate Thornton, ed., The Pulpit of the American Revolution; or, The Political Sermons of the Period of 1776 327 (1860).

Given the Bible’s pervasive presence in eighteenth-century culture, there is little surprise that the founding generation appealed frequently to biblical language and principles in their political discourse and deliberations.

Not all founders revered the Bible, but even those who doubted Christianity’s transcendent claims or the notion that the Bible was divine revelation thought it was vital to their experiment in republican self-government. (Interestingly, some of the most skeptical, heterodox founders, such as Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Paine, were the most prolific in referencing Scripture in their political writings.) Notwithstanding their varied backgrounds and personal theological views, including diverse views on God, Jesus, and even the divine origins and authority of the Bible, the founders valued the Bible for its insights into human nature, civic virtue, social order, political authority, the rights and responsibilities of citizens, and other concepts essential to framing a new political society. There was, in particular, broad agreement that the Bible was a useful handbook for nurturing the civic virtues that give citizens the capacity for self-government in a republic. For this reason, both John Adams and John Dickinson called the Bible “the most republican book in the world.”9John Adams to Benjamin Rush, 2 February 1807, in The Spur of Fame: Dialogues of John Adams and Benjamin Rush, 1805-1813 75-76 (John A. Schutz and Douglass Adair, eds. (1966) ; John Dickinson, notes [n.d.]. R.R. Logan Collection, Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Copy provided courtesy of The John Dickinson Writings Project, University of Kentucky. In various representative assemblies of the age, as well as in pamphlets, political sermons, and private papers, founding figures appealed to the Bible for principles, precedents, normative standards, and cultural motifs to define their community and to order their political experiments. Some founders also saw in Scripture, especially in the Hebrew Scriptures, political and legal models – such as republicanism and separation of powers – that they believed enjoyed divine favor and were worthy of emulation in their own polities.

The Bible was not an uncontested source of ideas. Neither did the founders always agree on the interpretation and application of Scripture to the great issues they confronted, as evidenced by bitter debates over slavery, the right to resist unjust rulers, prudential church-state relations, and the like. And yet ideas and values informed by Judaism and Christianity and their shared sacred texts were rarely removed from these difficult conversations.

The Bible and the Constitution

The United States Constitution hammered out in Philadelphia in 1787 gives evidence of a political vision informed, in part, by the Bible, and it includes features that were familiar to a Bible-reading people. Although it is difficult to establish definitively that constitutional provisions were derived from specific biblical passages, the lineage of selected constitutional principles can be traced to biblical concepts that had previously found expression in western legal tradition, especially in English common law, as well as in colonial laws and customs.10 It is a mistake to draw conclusions regarding the influence or absence of influence of the Bible or Christianity on the U.S. Constitution based solely on the number of references to God, Jesus, Christianity, and the Bible in the text of the Constitution or records of Convention debates. The surviving records of deliberations in the Constitutional Convention, including James Madison’s notes, are abbreviated and arguably unreliable. (There is no verbatim record of the Convention proceedings.) The delegates only occasionally referenced the Bible during debates on substantive provisions, according to surviving records, which some commentators have said indicates that the Bible had little or no influence on the Constitution. This analysis, however, misses the multiple channels through which the Bible exerted its influence on the legal culture and constitutional tradition that informed the Constitution.

Convention delegates occasionally invoked the Bible in surprising and interesting ways. In the Convention’s waning days, for example, during debate on the qualifications for public office, the venerable Benjamin Franklin spoke in opposition to any proposal that, in his words, “tended to debase the spirit of the common people. . . . We should remember the character which the Scripture requires in Rulers,” Doctor Franklin said, invoking Jethro’s advice to Moses regarding qualifications for prospective Israelite rulers, “that they should be men hating covetousness.”11 Benjamin Franklin, Constitutional Convention, 10 August 1787, as quoted in James Madison’s Notes of Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787, in 2 The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787 249 (Max Farrand, ed. (1911). Significantly, Franklin appealed to a biblical standard in this debate on a substantive constitutional provision, he informed his fellow delegates in unambiguous language that its source was “Scripture,” and then he appropriated specific biblical language (Exodus 18:21).

Beyond a few explicit references to the Bible in the sparse surviving records of Convention proceedings, the Bible’s influence on the Constitution was manifested in various ways. I will identify and illustrate several of those ways:

First, general theological or doctrinal propositions regarding human nature, civil authority, political society, and the like informed conceptions and institutions of law and civil government.

The Constitution’s basic design, defined by the separation of powers and checks and balances, reflected an awareness of original sin (Genesis 3) and the necessity to guard against the concentration or abuse of government powers vested in fallen human actors. This biblical anthropology, emphasized in Reformed theology, was expressed in the Constitutional Convention. James Madison, for example, acknowledged a fellow delegate’s strong view regarding “the political depravity of men, and the necessity of checking one vice and interest by opposing to them another vice & interest. . .. The truth was,” Madison concurred, “that all men having power ought to be distrusted to a certain degree.”12James Madison, Constitutional Convention, 11 July 1787, as quoted in i d., 1:584. Humankind’s fallen nature was a familiar theme in James Madison’s writings and, more generally, in the political literature of the founding era. Because men are not angels, Madison famously counseled in Federalist 51, “[a]mbition must be made to counteract ambition”; and in Federalist 37, Madison lamented “the infirmities and depravities of the human character.”13The Federalist 268, 185 (George W. Carey and James McClellan, eds. (2001).Various political traditions recognize the fallibility of human actors, but the tradition that most influenced Americans of the founding era on this point was Protestant Reformed theology.

Second, the founding generation saw in the Bible political and legal models that they thought worthy of their consideration and, perhaps, incorporation into their political and legal systems. For example, in Article IV, § 4, cl. 1, the Constitution requires every state to maintain “a Republican Form of Government.” The political discourse of the founding era is replete with appeals to the Hebrew “republic” described in the Old Testament – from the exodus to the coronation of Saul as king of Israel – as a divinely inspired model for republican government worthy of emulation in their own political experiments. In an influential 1775 Massachusetts election sermon, for example, Samuel Langdon, the politically active president of Harvard College and later a delegate to New Hampshire’s constitutional ratifying convention, opined: “The Jewish government, according to the original constitution which was divinely established, . . . was a perfect Republic. . . . The civil Polity of Israel is doubtless an excellent general model . . .; at least some principal laws and orders of it may be copied, to great advantage, in more modern establishments.”14Samuel Langdon, Government Corrupted by Vice, and Recovered by Righteousness. A Sermon Preached before the Honorable Congress of the Colony of the Massachusetts-Bay in New England, assembled at Watertown, on Wednesday the 31st Day of May 1775. Being the Anniversary fixed by Charter for the Election of Counsellors 11, 12 (1775). From various biblical passages chronicling the Hebrew polity, some Americans derived support for specific republican principles, such as government by consent of the governed as exercised through representatives chosen by the people.

Most of what the founding generation knew about the Hebrew commonwealth they learned from the Bible. They were well aware that ideas like republicanism found expression in traditions apart from the Hebrew experience, and, indeed, they studied these traditions both ancient and modern. Although the founders did not seek to replicate the Hebrew model in its details, its biblical precedent reassured many that republicanism was a political system approved by God.

Third, the U.S. Constitution includes provisions that are almost certainly derived from or informed by the Bible and Christian doctrine or practice. Again, the surviving records rarely reveal a Convention delegate citing Scripture when proposing specific constitutional provisions; rather, the delegates discussed selected principles and practices that were widely accepted in western legal tradition to have been informed by a biblical culture.

Consider, for example, Article I, § 7, cl. 2 excepting Sundays from the ten days within which a president must veto a bill. This is an implicit recognition of the Christian Sabbath, commemorating the Creator’s sanctification of the seventh day for rest (Genesis 2:1-3), the fourth commandment that the Sabbath be kept free from secular defilement (Exodus 20:8-11), and, in the Christian tradition, the resurrection of Jesus from the dead. “Sunday laws,” requiring a respectful observance of the “Dies Domini” or “Lord’s Day,” are rooted in a Christian reading of Scripture and are a familiar feature in legal regimes throughout Christendom. Leading common law jurists and commentators through the centuries have noted that Sunday laws, derived from the Bible and Christian practice, were affirmed in the customary laws of England.15 See, for example, Edward Coke, The Second Part of the Institutes of the Lawes of England. (1st ed. 1642), 220 (“no Merchandizing should be on the Lord[’]s Day”). Drawing on both biblical and English legal traditions, they were written into the laws of the colonies and, later, the states and the nation.

Article I, § 8, cl. 5 grants the Congress the authority to “fix the Standard of Weights and Measures.” Regimes for millennia have recognized the need for a uniform system of weights and measures. This concern was addressed in the English legal tradition before the Norman Conquest, but it was expressed most famously in Magna Carta, requiring standard measures and weights throughout the kingdom for various goods and produce. This provision, wrote Sir Edward Coke in his Institutes of the Laws of England (published in the mid-seventeenth century and widely recognized as a foundational textbook and definitive commentary on common law), was “grounded upon the Law of God.” Coke, the most eminent English jurist of the age, cited Deuteronomy 25:13-14 in support of this claim of divine provenance (“Thou shalt not have in thy bag divers weights, a great and a small. Thou shalt not have in thine house divers measures, a great and a small.”),16Id. 41. although he, like subsequent commentators, could have cited numerous other biblical texts as authority.17See, for example, Leviticus 19:35-36; Proverbs 11:1, 16:11, 20:10, 23.

The Article III, § 3, cl. 1 provision that convictions for treason be supported by “the testimony of two witnesses” conforms to a familiar biblical mandate, asserted in both the Old and New Testaments, requiring multiple witnesses of malfeasance for conviction and punishment (see Deuteronomy 17:6: “At the mouth of two witnesses, or three witnesses, shall he that is worthy of death, be put to death: but at the mouth of one witness he shall not be put to death”).18See also Deuteronomy 19:15; Numbers 35:30; Matthew 18:16; John 8:17; 2 Corinthians 13:1; 1 Timothy 5:19; Hebrew 10:28. The principle was written into early colonial laws, such as Article 47 of the Massachusetts Body of Liberties (1641), requiring “the testimony of two or three witnesses” in capital cases, and it continued to find expression in later statements of colonial law.19See George Lee Haskins, Law and Authority in Early Massachusetts 152-53 (1960) (discussion of the biblical origins and application of rules governing the number of witnesses needed in Massachusetts colonial law and English common law). The U.S. Supreme Court has noted that “the two witness requirement . . . was a familiar precept of the New Testament, and of Mosaic law.” Cramer v. United States, 325 U.S. 1, 24 and nn. 36 and 37 (1945).

The U.S. Constitution includes provisions that are almost certainly derived from or informed by the Bible and Christian doctrine or practice.

The Fifth Amendment, framed by the first federal Congress, prohibits double jeopardy, or trying a defendant twice for the same offence. In a late fourth-century commentary, Saint Jerome (and legal scholars ever since) said this was a principle found in the book of the prophet Nahum (see Nahum 1:9: “affliction shall not rise up the second time”). From these origins, the doctrine entered into canon law and English customary law and was transferred to American colonial codes and early state declarations of rights before it was eventually enshrined in the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. (Interestingly, in Bartkus v. Illinois [1959], Justice Hugo L. Black traced the biblical lineage of this principle.20See Bartkus v. Illinois, 359 U.S. 121, 152 n. 4 (1959) (Black, J., dissenting); Jay A. Sigler, A History of Double Jeopardy, 7:4 Am. J. Leg. Hist. 284 (1963): 284.)

The interpretation and application of the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on “cruel and unusual punishments” have provoked much controversy and debate. From early in the colonial experience, biblical law, even more than common law, informed American conceptions of cruel and unusual punishment. The Massachusetts Body of Liberties (1641), for example, included a prohibition on “inhumane Barbarous or cruell” punishments, and it limited corporal correction to “forty stripes,” as directed by Mosaic Law (see Deuteronomy 25:3: “Forty stripes he may give him, and not exceed: lest, if he should exceed, and beat him above these with many stripes, then thy brother should seem vile unto thee.”).21Massachusetts Body of Liberties (1641), arts, 46 and 43. Significantly, the limitation on corporal punishment was rooted in biblical law and a departure from common law. These provisions were reaffirmed in the Massachusetts Laws and Liberties (1648), as well as in subsequent laws of the Commonwealth and other colonies. The Mosaic injunction placing specific limitations on acceptable physical punishment also found expression in the regulations and laws of the new nation. Among the punishments for misconduct authorized by Congress in June 1775, a soldier in the Continental Army could receive a “whipping not exceeding thirty-nine lashes.”22Rules and Regulations, 2 J. of Continental Congress, 1774-1789 `119 Worthington C. Ford et al., eds. (30 June 1775). The first Congress under the U.S. Constitution similarly reflected Mosaic law when it authorized the punishment of flogging “not exceeding thirty-nine stripes.”23“An Act for the Punishment of certain Crimes against the United States,” 1st Cong., Sess. II, Ch. 9, 1 U.S. Statutes at Large 115-116 §§ 15, 16 (30 April 1790).

For one final example, commentators throughout American history have suggested that Christianity was incorporated into American legal culture in general and constitutional tradition in particular by way of English common law. As distinguished from statutory or civil law, the common law is the body of laws derived from principles, rules of action, customs, and prior decisions of judicial tribunals. The principal doctrine of common law is stare decisis, which requires judges to adhere to legal principles set forth in prior cases (precedents). A fundamental and enduring question in Anglo-American jurisprudence is whether Christianity is the basis of the common law. According to the most authoritative common law jurists in both England and America — including Sir Matthew Hale, Sir William Blackstone, Lord Mansfield, James Kent, Joseph Story, and Simon Greenleaf — Christianity is and always has been the foundation of the common law, and nothing in the common law is valid that is not consistent with divine revelation.24See generally Stuart Banner, When Christianity was Part of the Common Law, 16 Law and Hist. Rev. 27-62 (1998); Courtney Kenny, The Evolution of the Law of Blasphemy, 1:2 Cambridge L. J. 127-142 (1922); James R. Stoner, Jr., Christianity, the Common Law, and the Constitution, in Vital Remnants: America’s Founding and the Western Tradition 175-209 (Gary L. Gregg II, ed. (1999); and Christianity, the Common Law, and the American Order, in The Sacred Rights of Conscience: Selected Readings on Religious Liberty and Church-State Relations in the American Founding 537-87 (Daniel L. Dreisbach and Mark David Hall, eds.(2009). A popular, but not unchallenged, notion in the early republic was that, insofar as Christianity was the basis of common law and the U.S. Constitution accredited the common law, the American people incorporated Christianity into their organic law upon ratification of the Constitution. This claim has sweeping implications for the proposition that Christianity and its sacred text have informed American law, including constitutional law.

The influence of Christianity and the Bible on the American constitutional tradition arguably extends far beyond the handful of examples presented here. Scholars have identified additional constitutional provisions that reflect biblical influences. These include measures addressing due process of law, oaths and affirmations, emoluments, presidential pardon power, and corruption of blood. Among these and other provisions there are examples that, in the context of western legal culture, were almost certainly derived from a biblical tradition; in other examples, the Bible played a supporting role, buttressing or supplementing the rationales for a constitutional measure and reassuring a pious public that a provision bears a divine imprimatur.

If we miss or dismiss the Bible’s contributions to the American constitutional tradition, we distort our understanding of the nation’s bold constitutional experiment in republican self-government and liberty under law.

Tracing intellectual influences is not always easy or certain. In fact, it is often complicated and downright messy, and one is well advised to bring a strong dose of humility to the enterprise. Simply counting the number of biblical quotations and references to God and Christianity in the surviving records of the Constitutional Convention is not the only way to establish biblical influence on the Constitution, or the lack thereof. Evidence indicating influence is sometimes found in unusual and unexpected places. In the search for intellectual influences on the American founding, one must look wide and dig deep. And that includes plumbing the depths of civil law, canon law, and common law, as well as colonial laws and customs, for evidence of biblical influences that may have subsequently found expression in American law.

Conclusion

Some years ago, in a cover story on “The Bible in America,” Newsweek magazine reported that the Bible “has exerted an unrivaled influence on American culture, politics and social life. Now historians are discovering that the Bible, perhaps even more than the Constitution, is our founding document.”25Kenneth L. Woodward and David Gates, How the Bible Made America, Newsweek, Dec. 27 1982, at 44. Martin E. Marty, an eminent scholar of American religious history, similarly remarked, America “has more than the Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution enshrined in a vault in its archival heart. The Bible also is there.”26Martin Marty, America’s Iconic Book, in “Humanizing America’s Iconic Book: Society of Biblical Literature Centennial Addresses 1980”, 3 (Gene M. Tucker and Douglas A. Knight eds. (1982). In an increasingly secular age, the Bible’s place in the nation’s founding is much contested. Whether or not one accepts these statements regarding the Bible’s role in the creation of the new nation, the evidence suggests that the story of the American constitutional experiment cannot be told accurately or adequately without referencing the Bible. If we miss or dismiss the Bible’s contributions to the American constitutional tradition, we distort our understanding of the nation’s bold constitutional experiment in republican self-government and liberty under law.

The constitutional framers drew on multiple sources and traditions in crafting a new national charter in Independence Hall in the summer of 1787. Our understanding of that document is deepened by exploring the contributions of and interplay among the diverse perspectives that found expression in the framers’ constitutional experiments. Constitutional scholars read and study the Constitution; and to enrich their constitutional literacy, they are well advised to read and study, among others, Locke, Montesquieu, Blackstone, and, yes, the Bible. ♦

Daniel L. Dreisbach is a professor at American University in Washington, D.C. and an associated faculty at Emory University’s Center for the Study of Law and Religion. His research interests include the intersection of religion, law, and politics in American public life; and his published work includes Reading the Bible with the Founding Fathers (Oxford University Press, 2017) and Thomas Jefferson and the Wall of Separation between Church and State (New York University Press, 2002). You can follow him on Twitter @d3bach.

Recommended Citation

Dreisbach, Daniel L. “Does Biblical Literacy Enrich Constitutional Literacy? The Bible’s Forgotten Influence on the American Constitutional Tradition.” Canopy Forum, September 23, 2020. https://canopyforum.org/2020/09/23/does-biblical-literacy-enrich-constitutional-literacy-the-bibles-forgotten-influence-on-the-american-constitutional-tradition/