Rabbi Oren Steinitz didn’t set out to get the nickname Rabbi Vax. It happened about a year ago, amid a measles outbreak, after he expressed his pro-vaccination stance on a local radio show. Asked if he would ban unvaccinated people from entering synagogues, the rabbi replied, that if it were up to him, absolutely.

“Anti-vaxxers” from across the country sent the leader of Kol Ami synagogue in Elmira, New York, a slew of hate mail, claiming that vaccines are made from pigs and fetuses and that he was a “fake rabbi” who didn’t really know Judaism. He also received congratulatory emails from fellow religious leaders, telling him it was courageous to take such a firm pro-vaccination stance.

A few months later, he went to a conference and someone said, “Hey, it’s Rabbi Vax!”

Still baffled by the episode, the Israeli-born rabbi asks, “Since when did it become controversial to support science?”

The story is a lighthearted example that points to the critical influence religious leaders have in public’s attitudes on public health. Houses of worship have played key roles in helping communities get tested for COVID-19, and public health officials are counting on them to encourage their congregations to get vaccinated, as well.

“Pastors and other religious leaders are very powerful influencers in their communities,” says Kathryn Pitkin Derose, a senior policy researcher at Rand who specializes in the role that faith-based organizations play in public health. Derose calls clergy “natural partners” for the medical establishment.

While many in the religious community are supportive of vaccination efforts, some religious leaders are undecided — or outright opposed to — the vaccine. And that, too, could have implications for public health.

‘My spirit is not at rest’

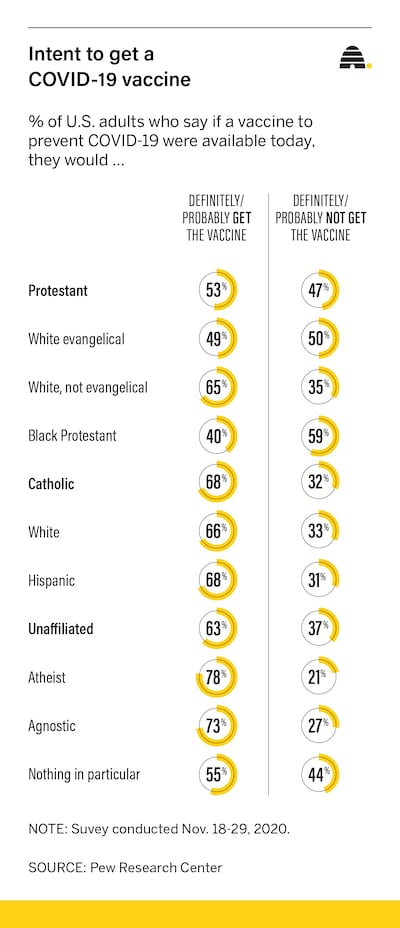

Pew Research Center reported earlier this month that 60% of Americans say they would probably or definitely take the vaccine. But demographic data of the survey provided to the Deseret News shows that two religious groups stand out for indicating they wouldn’t be vaccinated: 50% of white evangelicals told Pew they would definitely or probably not get the vaccine and 59% of Black protestants said the same.

The Rev. Traci Blackmon is senior pastor at Christ the King United Church of Christ — an almost all-Black congregation in Florissant, Missouri. The decision as to whether to urge her congregants to get vaccinated has weighed on her.

“I’m not disparaging it and saying, ‘Don’t do it,’ and I’m not saying to do it,” she says. “I don’t advocate things to other people that I’m not completely certain for myself”

The Rev. Blackmon urges congregants instead to “do their own research and come to their own decision.”

“They’ll have to make this decision without me ...” she says. “I get a lot of pushback about that but a lot of it comes from what your experiences have been and what your context has been.”

The Rev. Blackmon, who is a nurse by training, explains that her discomfort is rooted in her history. Born in Birmingham, Alabama in the early 1960s, She says she is “very familiar with the health disparities for Black communities.”

She was 9 years old when news emerged of the Tuskegee experiment — a 40-year syphilis study that was conducted on Black men who went untreated for the disease so that researchers could understand its progressive impact on the human body.

Tuskegee is about 100 miles from the Rev. Blackmon’s hometown.

“Proximity matters,” she says, “I grew up with a healthy skepticism of the medical establishment.”

The reverend believes in the need to fight the virus — her church distributes personal protective equipment to the community and has served as a COVID testing site. But she is deeply concerned about the speed with which the vaccine has been produced.

Her voice resigned, she adds, “It’s complicated for me. My spirit’s not yet at rest.”

In Baton Rouge, Louisiana, the Rev. Tony Spell will be directing his congregation not to take the vaccine. The leader of Pentecostal Life Tabernacle Church explains his opposition as “a religious conviction … we should not defile the temple of the living God — He dwells inside the physical body of the spirit of the believer.”

The Rev. Spell, who has been arrested dozens of times for violating Louisiana’s restrictions on gatherings during the pandemic, sees the vaccine as another divisive tool of the devil — an idea he touched on in a recent sermon.

“I tell you what the devil is doing in our nation today — it’s not about Democrat or Republican, it’s not about Black, white. It’s not about virus or no virus, mask or no mask,” he said from the pulpit on Dec. 13. “It’s about division, it’s about disunity ... it’s about us fighting with one another — all the while the world is dying on their way to hell.”

Catholic decision

The religious groups most amenable to the vaccine according to Pew were atheists, agnostics, Catholics, and white non-evangelical Protestants, in that order.

In a Dec. 11 statement, U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops called taking the vaccine “an act of charity toward the other members of our community.”

“In this way, being vaccinated safely against COVID-19 should be considered an act of love of our neighbor and part of our moral responsibility for the common good,” they wrote.

They also called getting vaccinated “an act of self-love.”

The bishops, however, advised against using the AstraZeneca vaccine, calling it “morally compromised” because it was developed using a cell line derived from “kidney cells taken from the body of a child aborted in the Netherlands in 1972.”

They urge Catholics to get the Moderna or Pfizer versions of the vaccine, but if those are unavailable, it would be “permissible to accept the AstraZeneca vaccine.”

“Given the urgency of this crisis, the lack of available alternative vaccines, and the fact that the connection between an abortion that occurred decades ago and receiving a vaccine produced today is remote, inoculation with the new COVID-19 vaccines in these circumstances can be morally justified.”

‘Faith in the experts’

While Jews and Muslims were not included in Pew’s data breakdown, Imam Abdullah Jaber, executive director of the Georgia branch of the Council of American-Islamic Relations, says that while the Muslim community is very diverse, most value science very highly and he anticipates they will get vaccinated in large numbers.

Rabbi Steinitz and Rabbi Joshua Lesser — who leads a congregation in Atlanta — both remarked that they expect Jewish Americans, in general, to take the vaccine in high numbers because of Judaism’s emphasis on the sanctity of life above all else. And, in recent days, a TikTok video of Rabbi Shumel Herzfeld participating in a vaccine trial this summer — and blessing God the moment after he received a “shot that can help save peoples’ lives” — has gone viral, garnering over 387,000 views and 65,000 likes.

“It’s about having faith in the experts who have been gifted by God to determine what’s best for us,” says Bishop Thomas Bickerton, who oversees 421 United Methodist churches in Eastern New York and Western Connecticut.

“Our social principles … speak to the dignity and worth of all people,” says Bishop Bickerton. An expression of this, he adds, is the belief that “everyone deserves access to health care and everyone deserves equal treatment.”

The United Methodist Church is gearing up to aid in the distribution of the vaccine and pastors telling congregants to “be aggressive about getting the vaccine and promoting that among others.”

Those types of efforts can play a part in public health, according to Derose. She and other experts are already talking to religious leaders in the Los Angeles area about “what would they be most interested in doing around … vaccines because we see a real potential there,” she says. “It’s particularly critical for the (Black) community and Latino community” — two groups that have a variety of concerns about the vaccine for different reasons.

“I want to emphasize that faith communities shouldn’t be expected to fill all the gaps that our public health system or health care system isn’t filling,” she says. “That’s not their purpose. Their purpose is to fulfill (congregants’) spiritual well-being and holistic well-being.”

Bishop Bickerton says he has already sent letters to the governors of New York and Connecticut offering United Methodist churches as vaccination sites.

But, for most Americans, it will take a while to get a dose. Meantime, Rabbi Steinitz (aka Rabbi Vax), is already talking about the vaccine with his congregation as a means of inoculation against another contagion: despair.

“Even though we don’t have a deadline for when things will be better, the main thing is to maintain some sort of hope that this is temporary … that there is a promised land somewhere on the horizon.

“We know we’re heading towards some sort of return to normal life,” he says. “This will only come when the vaccine is widely available and widely used. It’s not going to happen if people do not take it.”

alt=Mya Jaradat

alt=Mya Jaradat