(RNS) — As the case for sainthood for New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, based on his Emmy-winning performance during the pandemic, unravels, it’s anything but surprising that his administration is now, finally, doing something it should have been hard at work at many months ago: reaching out to houses of worship.

Doing so earlier was a no-brainer, especially given the easily anticipated problems for the vaccine rollout posed by the effects of systematic racism and ageism.

African Americans in particular have had a long and justified history of being skeptical of the medical system, and especially of new medical therapies. From forced experiments on slaves, to ignoring informed consent in Tuskegee syphilis trials, to the failure to account for Black patients in drug testing, to abandonment at the end of life today, anti-Black health measures have created a huge gap to be bridged when it comes to building trust in COVID-19 vaccines.

RELATED: Faith and the COVID-19 vaccine: ‘Using the Black church to get the word out’

Indeed, though Black Americans make up 13% of the U.S. population at large, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has found that only 5% of those who have received the vaccines thus far are Black. This, despite the fact that African Americans live disproportionately in communities significantly more at risk for COVID-19 infection and bear a disproportionate burden for comorbidities that make them more at risk for having a very bad outcome if infected.

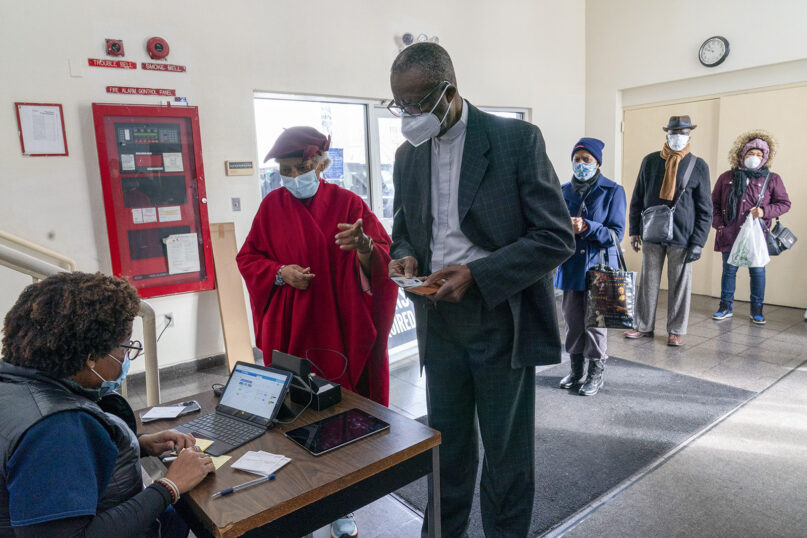

Access to the vaccine is another consideration, along with trust. The Black Church has already proved invaluable in some places from the earliest stages of planning. While Cuomo and others are now starting to figure this out, there is simply no excuse for Black churches in particular not being a central part of the effort.

This has created a scenario in which African American pastors are asking for more churches to be vaccine distribution sites but are instead taking backseats to community colleges, football stadiums and even abandoned buildings.

Another systemic problem for vaccine distribution is ageism, particularly as facility with technology has become a prerequisite to participation. Some 80% of COVID-19 deaths have been seniors, but in a recent report from Axios we learned that a whopping 42% of people over the age of 65 lack access to broadband internet.

Even more struggle as a matter of expertise to find and use online portals, most certainly losing out to younger, internet-savvier people. Indeed, a combination of unintuitive user interfaces and regularly crashing websites (which have frustrated even those who are quite good with technology) have caused many seniors to simply give up trying to register for a vaccine.

Study after study finds that both Black Americans and seniors are more likely to be deeply connected to their houses of worship compared to whites and younger people. Their churches, synagogues and mosques should be providing these populations with both access points for the vaccine as well as trust-building to bring in understandably skeptical groups.

States and the federal government must reach out to church leaders in a systematic way and ask for their help. And they must do so immediately.

Houses of worship don’t need to wait for this to happen in order to act. During the early months of the pandemic, my own pastor asked volunteers to sign up for phone bank slots — calling members of the parish to check on them to see if they needed help.

Any church can take steps like that, checking in with their membership list, finding out who needs help and reassurance and designating tech-savvy youth groups and other justice-centered committees to make sure vulnerable populations get protected.

RELATED: Churches in LA’s working-class neighborhoods urge: ‘bring the vaccine to the people’

The stakes are obvious. In Peñitas, Texas, an elderly couple passed away, one week apart, in the final week of January after being turned away for vaccination. During their 65 years of marriage, Gregorio and Petra had five children, 16 grandchildren, and 28 great-grandchildren.

Though the story is not totally clear about what happened, it looks like, just a couple of weeks before they died, they believed that there were vaccines available for them from their doctor’s office. But when they arrived for their shots they were told that none were available.

This kind of devastating story is repeating itself over and over and over again in families all across the country. As more vaccines become available, leaders in government, public health and houses of worship must do all we can to activate religious institutions in defense of these vulnerable populations. There is literally no time to waste.