The Interfaith Groups Preventing Muslim-Christian Violence in Nigeria

Sister Veronica Onyeanisi and other executives at WIC. Photo by Innocent Eteng.

LAGOS — By 2008, Kathleen McGarvey had flown from Ireland into Nigeria's state of Kaduna. The Catholic sister was in the country as part of her doctoral research, which partly aimed to determine to what extent women were involved in interfaith dialogue in Nigeria, especially in northern Nigeria.

For many decades, Nigeria's Muslim north has been prone to religious intolerance and violence. Kaduna, where over 20,000 people have died in different religious conflicts since the 1980s, is one of the country's most volatile states, and it was one of McGarvey's case studies.

Interfaith and reconciliation talks have been ongoing in Kaduna since at least 2010. But the groups leading such talks were all male-dominated, McGarvey confirmed in her research for her book “Muslim and Christian Women in Dialogue: The Case of Northern Nigeria”.

WIC flyers. Photo by Innocent Eteng.

If coexistence among people of different faiths must be achieved and sustained, women need to be critical players alongside men in peacebuilding, she thought. After all, they are also affected by faith-based hate and are sometimes involved in escalating it.

However, for that to happen, someone had to start getting religious women to think in that direction and to start acting, too, so she began consulting.

"She reached out to me and said, 'Why don't I start an NGO?'" recalls John Joseph Hayab, country director of Global Peace Foundation and chairman of the Kaduna chapter of the Christian Association of Nigeria (CAN).

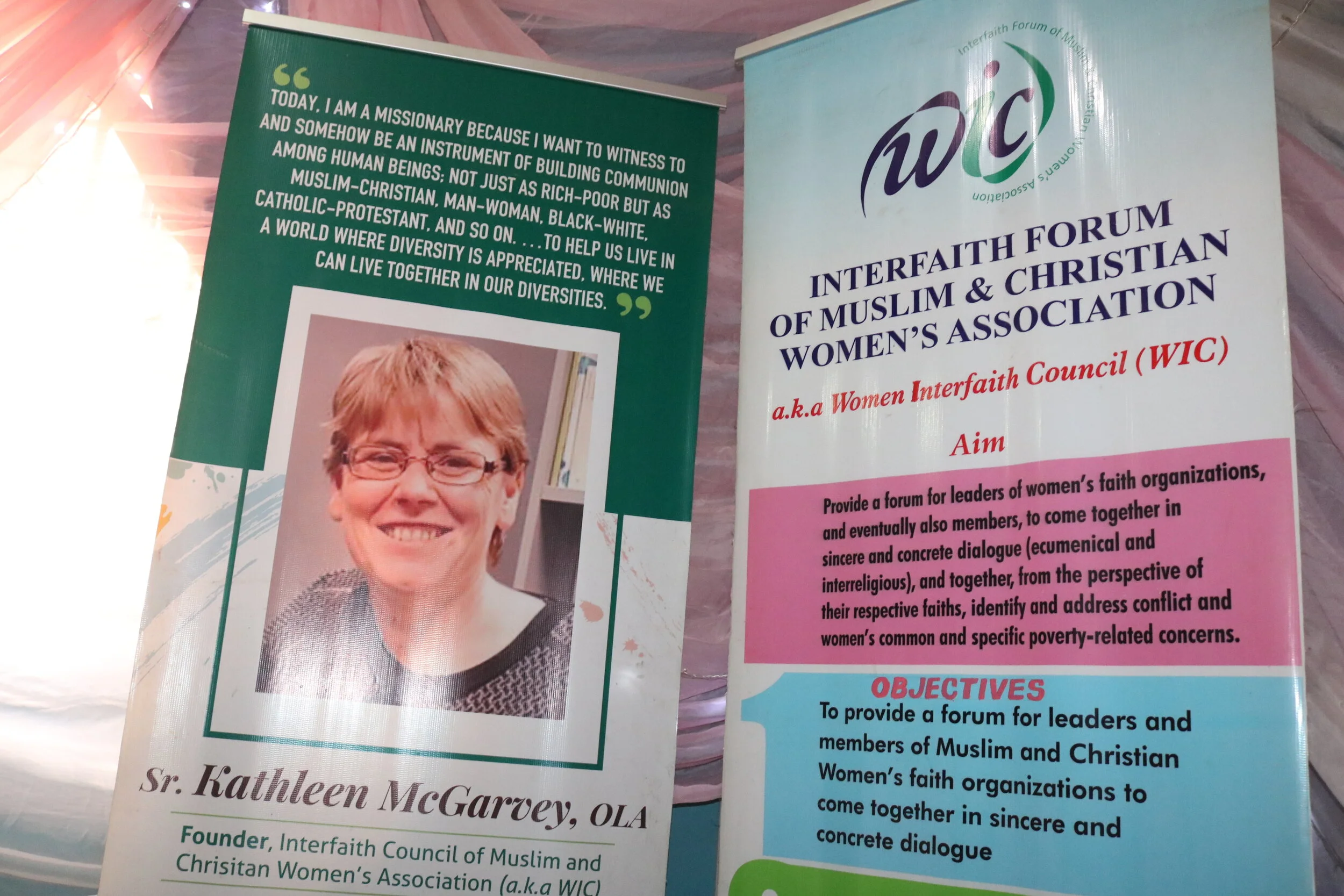

McGarvey's consultation later resulted in her founding the Women Interfaith Council (WIC) in 2010.

The nonprofit, also called Interfaith Forum of Muslim and Christian Women Association, serves as a platform for female religious leaders to come together for interfaith dialogue and extend the discussion to women in rural communities.

Today, with a leadership of women from different Islamic and Christian organizations in Nigeria, the group regularly visits secondary schools to preach tolerance to school kids and establish peace clubs to continue the conversation. They also organize peace talks for women in conflict-prone rural settlements.

In May 2018, for example, an ethnoreligious conflict between Muslims and Christians killed 13 people in Kasuwa Magani, a village in Kajuru Local Government Area of Kaduna, leaving followers of both faiths sharply divided. Three months later, WIC arrived and initiated a healing process.

"We were told that a Muslim could not buy from a Christian and a Christian could not buy from a Muslim [after the conflict],” said Juliet Aniango, WIC's secretary. “[So] we organized programs in the community and asked them [Christians and Muslims] to sit together and to make sure that at the end of the program, 'You know the house of the person you are sitting close to, and if there was a naming ceremony, a wedding or any functions [organized by a member of the other faith], you attend.’”

The effort, which also included organizing free vocational training for the women, worked. Within months, reconciliation spread across Kasuwa Magani, with WIC-led women actively involved in the process.

"Women have a lot to contribute in peacebuilding," said Sister Veronica Onyeanisi, WIC's executive director, citing the Kasuwa Magani success. "Most of the time, women are neglected. Society sees women as only the victim, but we found out that we cannot achieve peace without the women."

It is nearly seven years since McGarvey returned to Ireland in 2013. However, the WIC she left behind has grown to attract donations from many organizations, including the United States Institute of Peace, the King Abdullah bin Abdulaziz International Centre for Interreligious and Intercultural Dialogue (KAICIID), Sisters of Our Lady of Apostle (OLA), the Catholic Caritas Foundation of Nigeria, and the Open Society Initiative for West Africa.

The mediation center founded by a pastor and imam

In 1995, a warring pastor and imam in Kaduna decided to stop leading their people to kill each other and work for peace and forgiveness instead. The two had direct involvement in the Kafanchan crisis of 1987 that killed hundreds of people and the Zango Kataf conflict of 1992 that left more than 2,000 people dead.

Their minds changed after each suffered personal loss. Pastor James Movel Wuye lost his right hand. Imam Muhammad Ashafa lost two close cousins.

So Wuye, an Assemblies of God pastor, and Ashafa, an imam and spiritual head of the Ashafa Central Mosque in Kaduna, created the non-profit Interfaith Mediation Center (IMC) to help religiously divided groups and communities in Kaduna and Nigeria reconcile and commit to coexistence.

At precisely 10 o'clock, on the morning of Feb. 16, 2021, about 15 colleagues - a mix of Muslims and Christians, male and female - sat on armless chairs, forming a circle inside a conference room at the top floor of IMC’s two-story building located at 12 Constitution Road in Kaduna.

"Any news from Kogi?" asked Wuye, referring to one of Nigeria's north-central states.

"Kogi is peaceful," said a young man who had raised his hand to respond.

"How about Benue?" Wuye asked.

"There is tension in Benue over the migration of herdsmen [who sometimes violently attack communities with arms] to the state,” another voice said.

Wuye, right, and two colleague during a “Good Morning IMC” meeting Feb. 16, 2021. Photo by Innocent Eteng.

Throughout the meeting, Wuye inquired about the security situation of several other northern Nigerian states, probing for more details each time a response was negative. One man sitting next to him at a table wrote down every detail in a book.

The one-hour exercise, called "Good Morning IMC," takes place at the center every weekday. The state-to-state security reports are based on situation reports collected from the center's coordinators and "community peace observers" in different states.

Throughout the briefing, the center tracks security issues that could lead to ethnic or religious violence in Kaduna and other northern Nigerian states. Where IMC perceives a given security situation could heighten ethnic or religious tension, it quickly mobilizes its representatives in the state concerned to bring the two fighting groups to a dialogue.

And suppose state representatives are unable to handle it, the central leadership in Kaduna jumps in with its partner, the Conflict Mitigation and Management Regional Council or CMMRC, a network of former servicemen, religious leaders, traditional and community leaders and others working voluntarily to keep peace in Kaduna.

With a network of volunteers across several states and with support from organizations like the United States Institute of Peace, Christian Aid, Islamic Relief UK, British High Commission, and UNDP, IMC has helped several warring religious groups and communities in Kaduna and other states to forgive each other and coexist.

That includes working with the Kaduna State government to achieve the Kaduna Peace Declaration of 2000, which saw religious leaders agree to stop inciting violence and use dialogue to resolve future disagreements in Kaduna. The 2005 Yelwa-Shendam Peace Affirmation that saw Goemai and Yelwa - two ethnic communities in central Nigeria's Plateau State - reconcile after being involved in a religious crisis that killed more than 1,000 Muslims and Christians in 2004 alone was also primarily the making of IMC.

Often credited as the first and most vibrant interfaith house in Kaduna, IMC's most outstanding achievement is perhaps not its direct involvement in settling disputes but the center's provision of mentorship to dozens of people.

Some of those mentored or supported by IMC have gone on to work with other existing interfaith organizations, including Hayab, now CAN chairman in Kaduna and country director of Global Peace Foundation, and Yusuf Usman, former air force officer and now CMMRC chair who describes IMC as "our masters."

Peace-building efforts are multiplying

Some others have founded their own organizations, including WIC's McGarvey and Pastor Yohanna Buru of Peace Revival and Reconciliation Foundation of Nigeria, a Christian-led nonprofit that reaches out to Muslims with humanitarian services and peace talks.

Other local groups not directly linked to IMC have also emerged and are now contributing to the peacebuilding effort in this state with a near 50-50 Muslim-Christian population. Those include the Matthew Kukah Center with a mandate to promote conversations among followers and leaders of different faiths, and Carefronting, which adds interfaith dialogue as part of its many approaches towards preventing violent extremism in Kaduna.

The springing up of these local groups has made Kaduna the hub of interfaith organizations for peace and coexistence, those involved say.

And the impact has been positive in many ways because Kaduna has become less prone to religious intolerance and violence than between the early 1980s and early 2000s.

"In this place (Kaduna) before, a little issue would spark up killings. Now, even (with) serious issues, people are still asking questions, 'Is it true?' because there is a change in mindset. Now they know there are people they can ask; there is a procedure for doing things," said Hayab. "Before, people thought that if you do not hit hard, you would not solve the problem, not knowing that the more you keep hitting, the fight would never stop. [Now] there are tangible results, people [have] change[d], [there is] behavior change, [so] tangible that you can know."

Nevertheless, the proliferation of these groups has also created some conflicts of interest. For example, unlike IMC that focuses on trust-building through engagements and WIC that targets women, some other groups have no defined area of focus, leading to operational overlap.

"Overlapping of initiatives sometimes is not good; we are just addressing certain things in repeat," said Wuye. "But if there are clusters of initiatives and they are addressing certain thematic areas, it serves the purpose."

Also, pockets of violence are still being recorded, especially in southern Kaduna, where Fulani settlers clash almost regularly with the natives over land rights. Usman, the CMMRC chair, blames this on some religious leaders who still secretly incite their followers and on some politicians whose policies and dispositions favor one group against the other.

"Some of these people are our major problem. They are shadows somewhere. You do not see them. They are figures in communities," said Usman.

Despite this, the groups say they would keep working for peace with hopes that someday and someday, they would win over those fighting against peace.

"We want to see that (more) Muslim and Christian women relate very well, and when they relate very well, they will take it down to their families, trusting each other," said Onyeanisi. "And for the children, the young ones, to grow and know that a Christian and a Muslim are of the same family (of God)."

Innocent Eteng is a solutions-focused journalist based in Abuja, Nigeria. His reporting has been published by several media outlets, including The Christian Science Monitor, Yes! Magazine, TRT World, Women's Media Center, and Bhekisisa.