My late father, Congressman Tom Lantos, the only Holocaust survivor ever elected to the U.S. Congress, famously said, “The veneer of civilization is paper thin; we are its guardians, and we can never rest.” I have always taken this message as a personal call to duty — a pointed reminder that the responsibility for defending the values of a civilized world is both personal and permanent.

In some ways, this injunction from my father is a companion to the oft repeated plea “Never again.” These words, which refer to the Holocaust, have always held a deep and powerful meaning for me. For as long as I can remember, I have known about the horrors of that dark time in history and have felt an immense responsibility to ensure that such atrocities never again come to pass.

Today, however, I find myself increasingly concerned on two fronts: both about the shocking ignorance surrounding the Holocaust and about the rising tide of antisemitism around the world. This frightening trend should worry all people of goodwill, for when we permit historical illiteracy about the Holocaust to take hold, truly we are inviting history to repeat itself.

Antisemitism rises amid shocking lack of Holocaust knowledge

Only a few short months ago, the nation watched aghast as television networks broadcast images of neo-Nazis and white supremacists rampaging through the U.S. Capitol — one of them proudly wearing a shirt with the slogan “Camp Auschwitz.” This disturbing imagery was not an anomaly, but rather a symptom of a deeper disease.

According to the Anti-Defamation League, 2019 had the highest level of antisemitic incidents since it started tracking in 1979, and a newly released report shows that antisemitic incidents remained at historically high levels in 2020. At the Lantos Foundation, we focused the 2020 season of our podcast The Keeper on this most ancient and enduring hatred. One might wonder how such a rise in antisemitism can happen while survivors of the Holocaust, including my own mother, are still among us, living witnesses to that horror. But here, again, there is cause for alarm.

Results from a 50-state survey on Holocaust knowledge of American millennials and Generation Z, released last year, showed a shocking lack of understanding about this unparalleled tragedy in history. A full 63% of respondents ages 18-39 did not know that six million Jews were murdered during the Holocaust and 48% could not name a single one of the more than 40,000 extermination camps and ghettos in Europe.

An astounding 19% of respondents in New York believe Jews caused the Holocaust (11% nationwide), and 49% said they have witnessed Holocaust denial or distortion on social media. The spread of online antisemitism has undoubtedly fueled the disturbing rise in antisemitism, and it will make it even harder to rectify the problem of diminishing understanding about the horrifying genocide of the Jewish people during the Second World War.

As concerning as the situation is in the United States, it is perhaps even more troubling in Europe. The most recent example of this was the outrageous decision by the highest court of appeal in France to allow the murderer of Jewish woman Sarah Halimi to escape all justice and accountability for her brutal death. The Jews of France have good reason to wonder whether their government can be trusted to protect them.

Shared responsibility to advocate for persecuted religious minorities

Against this troubling backdrop, the Lantos Foundation for Human Rights & Justice — an organization dedicated to carrying on the proud human rights legacy of my late father – will hold our sixth annual Solidarity Sabbath. We launched this initiative in 2015 to shine a spotlight on the rising antisemitism in Europe and North America, and to bring together leaders from two dozen countries to express their support for and solidarity with the fight against antisemitism. Since then, the Solidarity Sabbath has become an opportunity to highlight the plight of other persecuted religious minorities and to encourage people from around the world to stand in solidarity with them.

People of all faiths, backgrounds, and political ideologies must come together in solidarity as guardians and keepers of the precious right of freedom of belief and conscience.

This year we wanted to use our Solidarity Sabbath to bring people from all faith traditions together to remind them about what it truly means to stand in solidarity with persecuted religious communities. We have partnered with the Combat Anti-Semitism Movement to offer a free virtual screening of a powerful new documentary, “Passage to Sweden,” which tells the story of how Scandinavian countries and individuals went to great lengths to protect, shelter and support their Jewish neighbors during World War II.

From the Danes saving their entire Jewish population, to Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg rescuing tens of thousands of Hungarian Jews, to the Swedes opening their country to Jewish refugees, the film opens the door for a much-needed conversation about why we must stand in solidarity with persecuted religious minorities, regardless of differences in our faith traditions.

The Talmud teaches that “whoever saves one life saves the world entire,” and the compassion and courage of people like Raoul Wallenberg surely underscore the significance and truth of this phrase. In a world that often feels irreparably divided by class, race, ideology and even by faith, we need more than ever to emulate his example of standing in solidarity with the most vulnerable among us.

We repeat the words “never again” to remind us of the Holocaust and to commit ourselves to never allowing such a genocide to occur. Yet, we have not been able to stop genocide in the years since the Holocaust, and we know it is happening even today. The repression and persecution of the Uyghurs, a Turkic-speaking Muslim minority that live in the northwest region of Xinjiang, China, undeniably constitutes genocide, defined by the United Nations as “acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group.”

While we can take heart from the increasing number of individuals and global leaders around the world who are speaking out on behalf of the Uyghurs and taking action to hold the Chinese government accountable for this abuse, we can also see the economic forces that are protecting and insulating the Chinese from the kind of consequences that would put an end to their genocide of the Uyghurs.

In other parts of the world, we see persecution of religious minorities on a less vast but still deeply worrying scale, from the Ahmadi community in Pakistan to the Rohingya in Myanmar, the Yazidis in Iraq, the Baháʼís in Iran, the Tibetans and Falun Gong in China, Christians in Nigeria, and the list goes on and on. Sadly, there is no shortage of persecuted religious groups who stand in need of our solidarity — in far flung corners of the world and, as we see with the rise of antisemitism, even in our own free, democratic nation.

The Jewish theologian and civil rights activist Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel wrote, “There is no limit to the concern one must feel for the suffering of human beings. ... in a free society, some are guilty, but all are responsible.” Rabbi Heschel’s words about our universal responsibility echo the biblical reminder to be our “brother’s keeper.”

People of all faiths, backgrounds, and political ideologies must come together in solidarity as guardians and keepers of the precious right of freedom of belief and conscience. It is one of the fundamental cornerstones needed to build free and just societies.

In our day and age, we will rarely need to take the kind of risks that heroes like Raoul Wallenberg did during the Holocaust, but we cannot hope to beat the scourges of antisemitism, bigotry or religious persecution without the collective power of brave citizens who refuse to be silent in the face of evil. We hope those who join us for this year’s Solidarity Sabbath event will learn from the powerful examples of the past and commit to standing in solidarity for the cause of religious freedom in the future.

Katrina Lantos Swett is president of the Lantos Foundation for Human Rights & Justice. She is a human rights professor at Tufts University and the former chair of the U.S. Commission for International Religious Freedom.

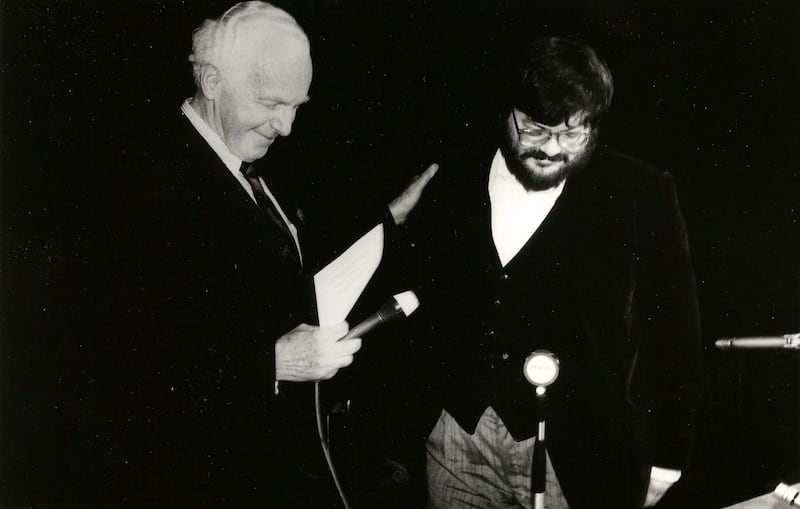

alt=Katrina Lantos Swett

alt=Katrina Lantos Swett