(RNS) — In May, after Florida authorities charged an Alabama man, Shannon Ryan, with second-degree murder in the case of a missing woman, Leila Cavett, the headlines led not with the sudden development in a year-old investigation, but with a random detail about the suspect’s life.

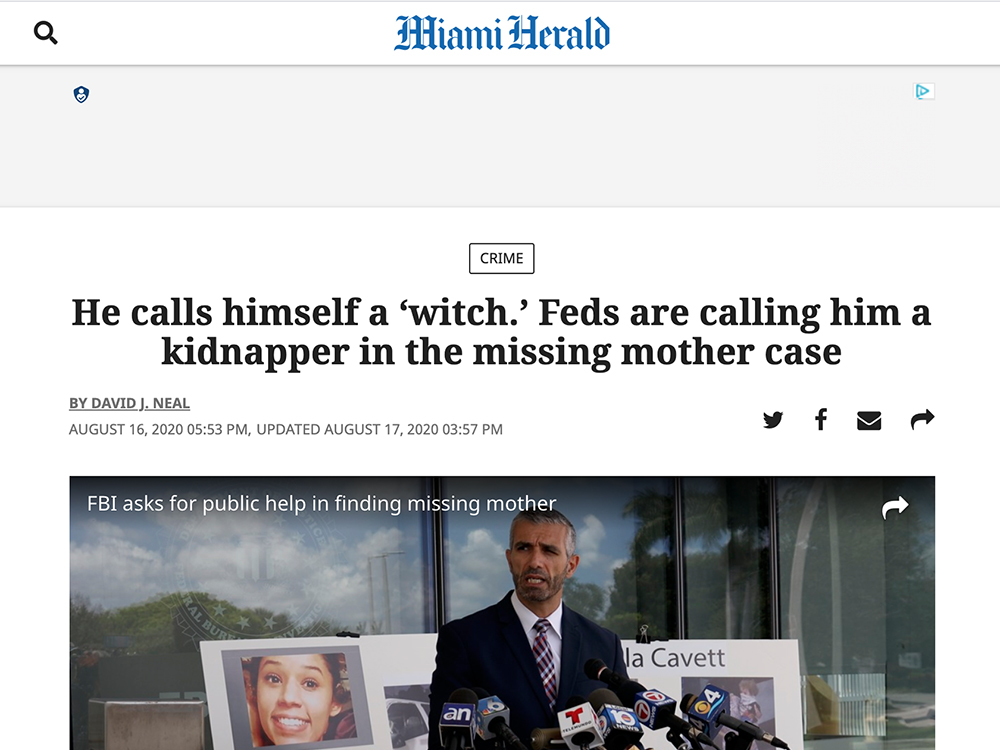

“He calls himself a ‘witch.’ Feds are calling him a kidnapper,” read one banner.

“Alabama ‘witch’ charged with murdering Florida woman” began another.

Ryan had made no attempt to hide his spiritual practice. Since 2017 he has posted to a Facebook page he called Magnetic Kundalini that addresses “Witchcraft, Knowledge of Self, Kemetic Kundalini & Chakra meditation, Kemetic Science, Health, wellness, fitness, mentorship.”

RELATED: Pagan ‘metaphysical’ shops navigate threats from Christian critics

But since his arrest, some witches have pointed out that, despite the headlines, Ryan’s alleged crime does not appear to have any relationship to his beliefs.

A recent Miami Herald headline about Shannon Ryan. Screengrab

This doesn’t happen to people of other faiths, said Seba O’Kiley, who, like Ryan, hails from Alabama and practices witchcraft. “Criminals aren’t labeled as Baptist,” O’Kiley added, unless the crime is in some way related to professed religious beliefs, as was the case in the recent spa shootings in Atlanta.

“This is irresponsible reporting,” said O’Kiley. “It is putting us all in so much danger.”

O’Kiley said that discrimination against witches in her state has kept her from identifying herself publicly, instead remaining “in the broom closet,” she said, adapting a term from the LGBTQ community to indicate hidden identity.

“We’ve lost jobs here. We’ve been threatened here,” said O’Kiley.

O’Kiley’s concerns are not unfounded nor limited to Alabama. A 2015 Florida headline reported “Witch’s son in DeLand gets 65 years for child porn.” In 2017, New Orleans outlets included “Wiccan Priest” in headlines after a child pornographer was convicted.

In January 2021, several articles about a murder-suicide case defined a West Virginia woman as being “obsessed with witchcraft.” In May, a Virginia woman charged with killing her child was, as one headline reads, “into witchcraft.”

In these stories, any implied connection between the crime and religious belief or community, if it existed, is never made explicit.

The Rev. Selena Fox. Photo by Robertpaxton/Creative Commons

The Rev. Selena Fox, executive director of Lady Liberty League, a pagan religious freedom and civil rights organization, said, “To use the word witch in connection with crime reporting is a mistake unless the reporter is truly going to do an in-depth analysis of the person’s background.

“Witch is a loaded term,” Fox said. “It is a complicated term and it’s been used as a weapon as part of hate crimes around the world.” No matter how the term draws attention, reporters and editors should look at “all identity factors,” not just religious practice, she said.

In 2017, the United Nations Human Rights Council for the first time formally addressed the global crisis of witchcraft-related violence, which in some countries has led to stoning, dismemberment and execution.

In the United States, identifying as a witch publicly or simply being labeled one may not come with the same level of risk. However, there are risks, especially in rural areas.

“The primary danger is always employment” O’Kiley said. In 2014, she lost her job, which she maintains was directly related to being outed by a co-worker. In March 2021, a Pennsylvania pagan filed a lawsuit against her employer, Panera, after being fired. She also alleges religious discrimination.

The second-biggest danger, according to O’Kiley, is intimidation. In 2018 in Auburn, Alabama, O’Kiley recalled, a group of young men, led by a Christian preacher, circled attendees at the annual Pagan Pride Day. Similar occurrences have happened across the country at pagan pride events.

Even New York City’s progressive Greenwich Village is not immune. In 2016, loud street preachers disrupted WitchFest USA, an annual outdoor pagan festival.

O’Kiley believes the rural South is one of the most difficult areas to be a witch, despite the fact that magic is not foreign to Southern culture. Much of traditional American witchcraft rose from syncretic practices combining Christianity with indigenous spiritual or folk practices from the Americas, Africa or Europe.

O’Kiley learned her own practice from both of her grandmothers and her nanny. “We are healers,” she explained, who understand the local plants and their medicinal benefits. “We make teas and poultices. We know how to bless things.”

In her memoir “Finding Magic,” journalist Sally Quinn recounted her introduction to and practice of magic growing up in the South, a mixture of what she calls Scottish mysticism and voodoo. “I began to see the power of the mystical, the mysterious, and the magical,” she wrote. “I had a glimpse of the spiritual as a possible substitute for religion – unorthodox as what I was seeing, and feeling may have been.”

However ingrained, magic is disguised, with spells called prayers and witches healers. Sometimes witchcraft bears the name folk magic, if it is called anything at all.

RELATED: The next stage of witch resistance is here

O’Kiley would like to be more public about her practice. “There are ways we can live peacefully with our Christian neighbors,” she said. But the “witch” buzz in her local community after reports of Ryan’s arrest reminded her why she stays mostly hidden.

“It is too bad,” she said. “Witches pay taxes. We are voting citizens. We are girl scouts. We are invested in our communities.” When reporters use ‘witch’ simply as a derogatory label, she said, “they suggest it’s the ‘worst thing a person can be.’”

“Am I the worst thing a person can be?” she asked. “I heal people. I am not a criminal. Heck, I don’t even speed.”