‘The Last Acceptable Prejudice’

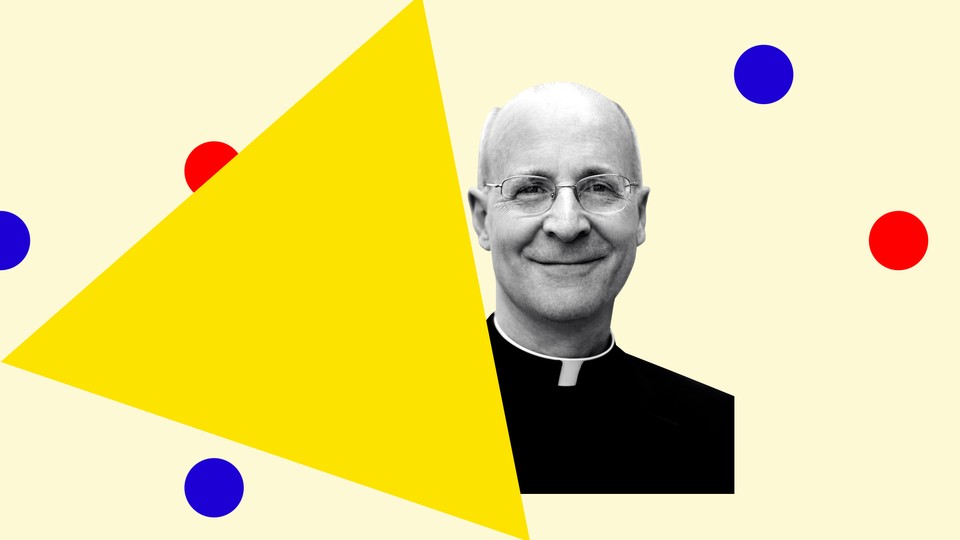

Father James Martin isn’t quick to call out bias against his faith. But sometimes people go too far.

In early July, The New York Times published two articles that had seemingly little to do with one another. One covered the Entomological Society of America’s decision to stop using the terms gypsy moth and gypsy ant. The other was about a new movie by the director Paul Verhoeven featuring an affair between two 17th-century nuns. “Forgive them, Father, for they have sinned,” the article begins. “Repeatedly! Creatively! And wait until you hear what they did with that Virgin Mary statuette.”

“When I read that article in the morning over my yogurt and cranberry juice, I couldn’t believe what I was reading. It was just disgusting,” Father James Martin, a Jesuit priest and writer, told me. He was talking about the movie, not the moths. He found it striking that the Times would deferentially cover a language shift meant to show respect for Roma people but would also print a story that relished a film scene in which a holy Catholic object is defiled. “Anti-Catholicism is the last acceptable prejudice,” he wrote on Twitter, linking to an article he wrote 20 years ago that explores why some Americans still treat Catholics with suspicion or contempt. His argument, then and now, is that it’s acceptable in secular, liberal, elite circles—such as The New York Times—to make fun of Catholicism, particularly the Church’s emphasis on hierarchy, dogma, and canon law and its teachings related to sex.

Martin is well known in the American Catholic world for his relatively progressive approach to issues that have split the Church, including advocating for greater Catholic acceptance of LGBTQ people. As a result, he’s a frequent target of opprobrium from many of the conservative Catholics who tend to protest anti-Catholicism most loudly, which is why I wanted to talk with Martin: He is deploying arguments similar to those of his critics. We are living in an era when newsrooms are revising their style guides to be more sensitive about race, gender, and sexuality; flippant comments perceived as bigotry can cost people their job; and entomological societies are scouring their insect rosters for pejorative names. Yet, some aspects of identity and belief still seem to be fair game for mockery.

Our conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Emma Green: The New York Times wrote up this new movie called Benedetta and its debut at the Cannes Film Festival. The article—written by a reporter, not a critic—is very taken with the movie’s lesbian nun sex. They apparently use a statue of the Virgin Mary to do something that I can’t actually say out loud to you because you’re a priest. When you read this, why did it strike you as anti-Catholic prejudice?

James Martin: Well, first of all, it’s very subjective. One person’s critique is another person’s anti-Catholicism. Second of all, we have to be careful not to label every single critique of the Church as anti-Catholicism. The Church deserves its critics, especially in the light of the sex-abuse crisis and financial scandals and other things.

What bothered me more than the film was the article. The fact that you had a hard time describing what the article said to me should be an indication of its offensiveness. What if it were directed toward another religion—something holy from Islam or Judaism being used as a sex toy—and that was made fun of in The New York Times? To me, it seemed unnecessarily mocking.

Green: Why do you think it feels more acceptable to some people for The New York Times to write like this about Catholics than about, say, Orthodox Jews?

Martin: I think anti-Catholic tropes get a pass in our culture for a number of reasons, in a way that anti-Semitism, anti-Islam, or even homophobia do not. The tone of the article was: Isn’t this funny? Isn’t this silly? Isn’t Catholicism ridiculous?

Green: Do you think this is because people assume that the Catholic Church is powerful, and many Catholics in America are white and are part of the Christian cultural majority? Is it that making fun of powerful people or institutions doesn’t seem out of bounds?

Martin: We’ve always lived in a largely Protestant culture that has been suspicious of Catholicism—papal infallibility, the Virgin birth, celibate priesthood. And there’s a long history in the United States of anti-Catholic tropes. There are many reasons, including distrust of authority, and a misunderstanding of celibacy and chastity.

Green: I’ll show my cards, which is that I don’t care that much about one movie or the way it’s written about in The New York Times. But this sparked my interest because it’s arguably an example of the ambient cultural signals that build a sense, especially among some conservative Catholics, that they are culturally on the outs. You’re not typically in that camp, grinding the ax around how oppressed Catholics are. In this instance, do you have any sympathy for that point of view?

Martin: Cries of anti-Catholicism are too frequent. Anti-Catholicism is nowhere near as prevalent as racism, homophobia, or anti-Semitism. Not every critique of the Church is an offense against religious liberty. And The New York Times is not anti-Catholic. But from time to time, it’s important to remind people that anti-Catholicism is not a myth.

Green: I wonder if there are instances where this has become politically complicated for you. For example, when now–Supreme Court Justice Amy Coney Barrett was in her hearing for the Circuit Court of Appeals, Democratic senators questioned her about how her Catholic faith would affect her rulings on issues like abortion. Senator Dianne Feinstein famously told her, “The dogma lives loudly within you.”

A lot of people thought that was open anti-Catholic bigotry—a U.S. senator expressing fear that an accomplished legal scholar couldn’t be a fair judge because of her faith. Did you think they had a point?

Martin: Well, first of all, I thought that that phrase was inherently funny. The dogma lives loudly within you. It was just strange—almost nonsensical. But I think it was appropriate for Senator Feinstein to ask, “To what extent will your religious beliefs influence your legal decisions?” That’s not unreasonable.

Green: Do you think so? I mean, the Constitution says that no religious test should be required as a qualification for public office. It’s a founding principle of our country that Americans don’t consider religion when we vet people as public servants.

Martin: I think the difference is that Justice Barrett is well known as a devout Catholic. I didn’t think that was an offensive question. The way it was put was a little ham-handed.

Green: There are other examples of this. Now–Vice President Kamala Harris, for example, questioned judicial nominees about their participation in the Knights of Columbus, a Catholic men’s organization, supposedly because it would indicate something about their fairness on issues like abortion and their fitness to serve. I don’t have to tell you, members of the Knights of Columbus are mostly Catholic dads holding fish fries in the suburbs.

Martin: I think that betrays more of a misunderstanding of the Knights of Columbus on Harris’s part. But here’s the point: If religion wants to be part of the public square, then it’s reasonable for the public square to ask questions about religion.

Green: What I’m driving at is that for someone like you, in particular, I think it might be easier to read a New York Times article and see it as disrespectful. But it might be harder for you to say, for example, that the city of Philadelphia was showing anti-Catholic bias when it penalized a Catholic adoption agency for refusing to certify LGBTQ couples as prospective parents. Yet, these political examples—if they truly are anti-Catholic bias—are way more consequential to people’s lives than a Verhoeven film or a New York Times article.

Martin: Even small things, like a New York Times review, contribute to an atmosphere where Catholicism is seen as silly, and I think that makes it more difficult for people to have conversations about faith overall. I actually think the two things you’re talking about are intimately connected. Debate about difficult topics related to religion has to be accompanied by respect. You might want to talk about birth control, abortion, or religious liberty, but do it respectfully. If you are swimming in this culture of disrespect—of mocking and belittling—that makes it harder for people to even know how to approach these topics.

Green: Do you still think anti-Catholicism is the last acceptable prejudice?

Martin: Yes, I do. The kinds of things you read about Catholics would never be tolerated for other religions. The faith is treated as a joke. People see chastity and celibacy as a negation of sexuality, so they see it as a threat. But I often point out to people: You know people who are celibate and chaste. You know people who are single. You know aunts and uncles. You know widows. No one thinks they’re insane or disgusting or pedophiles or dangerous. But when a person chooses it freely, suddenly they become a freak.