ROME – After lawmakers in Queensland, Australia, voted overwhelmingly in favor of a measure allowing for Voluntary Assisted Dying (VAD), one of the country’s top bishops condemned the move as a “defeat for life.”

In a Sept. 16 tweet after the legislation was passed, Australian Archbishop Mark Coleridge of Brisbane said, “The die is cast, and across the Rubicon we go.”

“Some kind of victory for the government but a real defeat for Queensland, a victory for death but a defeat for life…now we await the dark spectacle of unexpected consequences,” Coleridge said. Brisbane is the capital of Queensland.

Coleridge insisted that despite the new laws, Catholic healthcare providers, “whose voice has been merely tolerated in this process,” will continue to accompany “all kinds of people to death and beyond compassionately and peacefully…as we have for a very long time.”

Parliamentarians in Queensland, Australia’s second largest state, passed the new VAD laws during a Sept. 15 vote, which ended 60-29 in favor, making Queensland the fifth Australian jurisdiction to allow voluntary euthanasia laws.

Various faith-based groups led a fierce campaign in the lead up to Wednesday’s vote, proposing various amendments aimed at placing strict barriers for gaining access to the so-called “right to die.”

In the end, after 55 amendments were proposed, debated, and rejected, the legislation passed in its original form.

Back in May, Archbishop Patrick O’Regan of Adelaide cautioned about what impact the bill could have “on vulnerable people and on our Catholic health care providers.”

He also accused the legislation as violating human dignity, saying, “No-one wants to see people suffer unnecessarily at any time, especially at the end of life, but the compassionate way to achieve this is through high quality, well-resourced palliative care.”

“Assisted suicide undermines the fundamental principle of the equal worth of all human individuals by legally enshrining the idea that some human lives are not worth living,” he said, adding, “By making such ideas law, it gives the impression that this attitude is the proper attitude of and for our society. Such a message puts vulnerable people at risk of coercion and elder abuse.”

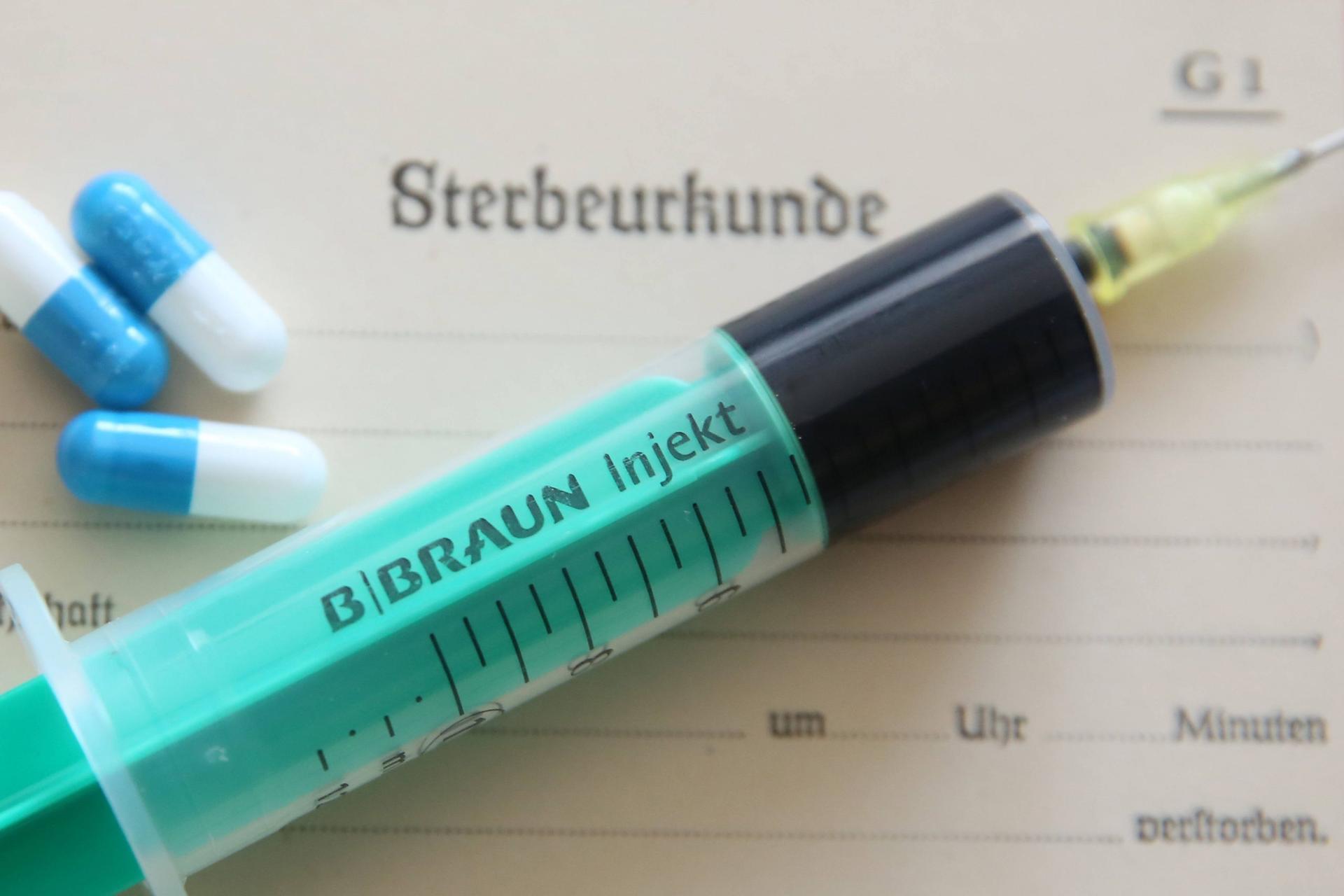

Under the new law, access to Voluntary Assisted Dying will be restricted to people with advanced and progressive conditions which cause unbearable suffering and who are expected to die within a year.

These people must be alert and able to make decisions. If they wish to avail themselves of their VAD rights, they must be separately and independently assessed by two different doctors, and they will also be required to make three distinct requests over a period of at least nine days.

Doctors and other healthcare professionals will apparently maintain their right to conscientiously object, however, some faith-based opponents of the law have argued that these provisions do not go far enough.

As debate on the bill was ongoing, Coleridge, in a series of tweets, warned that the new laws could “jeopardize” the longstanding collaboration between Catholic healthcare providers and the Queensland government.

Parliamentary debate, he said, was “heavy on politics, anecdote, platitude and sentimentality,” but there was not much to suggest “that all members understand the deeper issues or are competent to make the decision before them.”

Referencing rumors that a set of guidelines had been put forward to address the concerns of religious health and elderly care providers, Coleridge voiced skepticism, saying, “What I’ve seen aren’t guidelines but very brief and vague hints at what proper guidelines might contain.”

In an article published in The Australian, Jesuit Father Frank Brennan, rector of Newman College at the University of Melbourne, voiced concern over three factors he said were especially worrying, the first of which is that under similar legislation passed in the Australian state of Victoria, it is unlawful for a registered health practitioner to broach the subject of VAD with a patient they are treating, while this is legal in Queensland.

“The last thing ageing, sick people need is evangelizing health practitioners prompting them to consider VAD. The Victorian law precludes that; the Queensland bill encourages it,” he said.

Brennan also warned that while in Victoria a doctor is able to opt out of all aspects of euthanasia simply by telling their patients that they have a conscientious objection to it, the Queensland law urges healthcare providers with moral concerns about VAD to direct their patient to another doctor who is willing to assist.

Finally, Brennan argues that while hospitals and nursing homes in Victoria can maintain principled objections to VAD, giving notice to all patients and residence that VAD procedures will not be provided due to religious reasons, the Queensland law “provides access for consulting VAD practitioners to facilities that do not provide VAD.”

In a Sept. 16 statement, Catholic Health Australia Chair John Watkins said that Catholic health and elderly care providers are “deeply disappointed” by the passing of the law, “which so clearly conflicts with their ethic of care.”

“We have made it clear all along to the Government that we will not allow voluntary assisted dying in our hospitals or aged care facilities, yet the Parliament has passed a law that forces us to do so,” he said, arguing that the new law “places us in an invidious and extraordinary position.”

Watkins said that being forced to host VAD in their facilities “means having our most deeply held beliefs around the dignity of human life trampled upon.”

“Many of our members have served their communities with compassion and professionalism for more than a century and will continue to do so even in the face of such a law,” he said, adding that in the coming months, they will be working with the government “on a system that reconciles our beliefs with its laws.”

Follow Elise Ann Allen on Twitter: @eliseannallen