There are some concepts in political science that have just become impossible to ignore. Whether it’s leading a classroom discussion, talking to a member of the media, or just chatting with friends about the current state of the world, I can’t help but bring it all back to political polarization.

Put simply, it’s the idea that American society has become more politically tribalized, with Democrats huddled in the far left corner of the political spectrum and Republicans doing the same on the right side of the scale with a huge chasm between the two. And, the two parties loathe each other — not just disagreeing, but believing that if the other party wins an election, it will lead to the end of the Republic.

Compromise becomes impossible in a world in which you see the other side not only as wrong, but also as the enemy. The inherent problem is that our democratic processes grind to a halt without a level of bi-partisan support.

There’s been a ton of great research done on measuring the level of polarization in the United States Congress by using DW-NOMINATE scores. The results indicate that both parties have moved away from the center, but that is more pronounced among the GOP than among the Democrats. This visual (it comes from this paper) is one I use in class to show just how bad it’s gotten.

But, I wanted to take a different approach here. I wanted to see just how much polarization is perceived by the average American, how that has changed over time, and how religion plays a role in that perception.

Here’s how I did it.

Since 2012, the Cooperative Congressional Election Study has asked respondents a battery of questions that require them to place the Democratic Party, the Republican Party, and themselves on an ideology scale running from 1 (very liberal) to 7 (very conservative), with the moderate option described as “middle of the road.” For my purposes someone has a polarized view of the world if they describe either the Democrats as “very liberal” or the Republicans as “very conservative.” In essence, they are saying: “that political party can’t get any more extreme.”

Let’s take a longitudinal look to begin with, then dig in on what’s been happening in 2019 (the latest year for which data are available).

I divided the sample up into four categories: those who say that the Democrats are very liberal, those who say that the Republicans are very conservative, those who say that both things are true, and those who say that neither is true. Then, I tracked those changes across sixteen religious traditions and six survey cycles. Hi res/zoomable here.

There’s a lot to discuss here.

For most of the larger traditions the share that sees neither party as polarized has declined significantly from 2012. For instance, 43% of mainline Protestants didn’t see either party as extreme in 2012, now it’s just 25%. For Mormons, it’s dropped from 42% to 30%; for Jews it’s a 14 point drop (42% to 28%). The group that moved the most on this measure are atheists. In 2012, 43% didn’t see either party as polarized, but in 2019 that had dropped to just 18%. That’s almost all attributable to more atheists seeing the Republicans as being “very conservative.”

That’s the other big part of this story — very few people see both parties as being to the edges of the ideology spectrum and most people perceive extremism to be tied to one political party but not the other. For most traditions, the share that sees bipartisan polarization is below 10%. The reality is that the more conservative traditions see the Democrats as becoming more extreme and the reverse is happening for more liberal religious groups.

White evangelicals epitomize this finding. In 2012, 46% of them saw the Democratic Party as very liberal. By 2020, that had jumped to 60%. At the same time, the share who saw the Republicans as very conservative stayed steady at around 10%. The pattern for atheists is even more exaggerated with 68% of atheists seeing the GOP as very conservative in 2019, but less than 10% seeing the Democrats as being very liberal. For both white evangelicals and atheists, 80% of them see the political world as polarized.

For non-white respondents, though, polarization is lower. A non-white evangelical was half as likely to see the either party as extreme in 2019, and 42% of non-white Catholics see the political world as polarized in some way.

But, are views of polarization equally distributed for both conservatives and liberals?

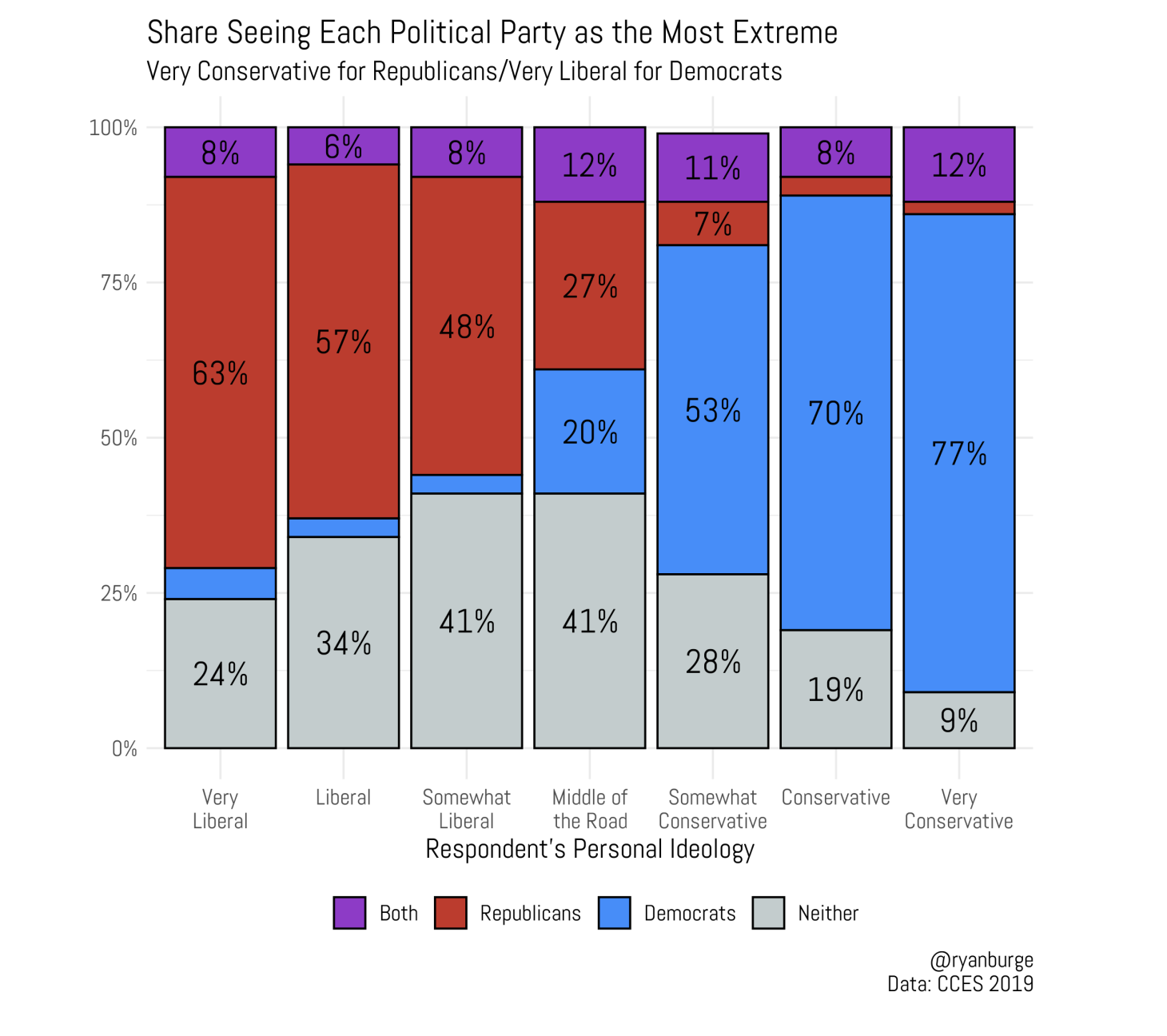

Said another way: are those on the right just as likely to see those on the left as extreme as the reverse? To answer that I did the same analysis with 2019 data and divided the sample based on how they described their personal ideology.

Clearly, as one describes themself at the edge of the ideological spectrum, that changes their views of the two parties. The individuals who have the least polarized view of the world are those that see themselves as “middle of the road” or “somewhat liberal.”

But, it’s also clear that perceptions of polarization are asymmetric. Comparing a very liberal respondent to a very conservative respondent makes that clear.

CONTINUE READING: “Does Church Attendance Help to Reduce Perceptions of Polarization? Not Among White Conservatives” by Ryan Burge.

FIRST IMAGE: Political polarization graphic posted at ThriveGlobal.com