MECCA, Saudi Arabia (RNS) — Mariam is sipping on a juice box while sitting on the front steps outside a hotel not far from the Grand Mosque in this holiest of cities for Muslims. Mariam first says she is 10 years old, but then decides she is 8.

Her mother, in a black abaya and a face veil, is sitting a few steps away on the pavement, selling scarves to a group of pilgrims.

It is 6:30 a.m. and dozens of pilgrims stop as they walk back to their hotels after performing fajr, the morning prayer at the Grand Mosque.

Mariam’s mother is one of several vendors selling an assortment of items to pilgrims walking by. This is the first time in over two years that they have been able to do so, after Saudi Arabia recently relaxed most COVID-19-related restrictions.

RELATED: Like many hajj traditions in a pandemic year, Zamzam water gets a reboot

“She will finish soon and then we are going to go back home and sleep,” said Mariam, her eyes glued on her mother the entire time. “It is going to get too hot to be outside anyway.”

In another hour, Mariam’s mother packs up the few scarves she wasn’t able to sell and is ready to go back home.

Umrah pilgrims walk to the Grand Mosque one morning during Ramadan in mid-April 2022, in Mecca, Saudi Arabia. A Grand Mosque expansion project can be seen in the background. Photo by Rabiya Jaffery

“It has been very difficult two years,” she says politely, despite evident hesitation to speak to a stranger. Mariam and her mother, who declined to give her name for safety reasons, are of Somali heritage and are among the 5 million undocumented migrants living in Saudi Arabia.

“It is not that much easier now for us either. We are just making ends meet till we are caught and deported. But alhamdulillah” — praise God — “we got at least one normal Ramadan again. Hopefully, we also get hajj before we are kicked out.”

For two years, as COVID-19 raged around the world, the Saudi government, custodian of the holy sites in Mecca, closed the country to outsiders, barring those who come to make the Umrah pilgrimage during Ramadan and the more than 2.5 million pilgrims who in a normal year make the required visit to Mecca, or hajj.

Besides the spiritual deprivation, the closure severely dented the country’s gross domestic product and pinched traders such as Mariam’s mother who depended on the pilgrims.

But the worst might be over: The Ministry of Hajj and Umrah has announced that the limits on this year’s hajj, which begins in July, have been relaxed to a million pilgrims — more than the 50,000 allowed in 2021 and the 1,000 in 2020, at the height of the pandemic. Occupancy rates at leading hotels in Mecca have already increased to 95% in the first week of Ramadan.

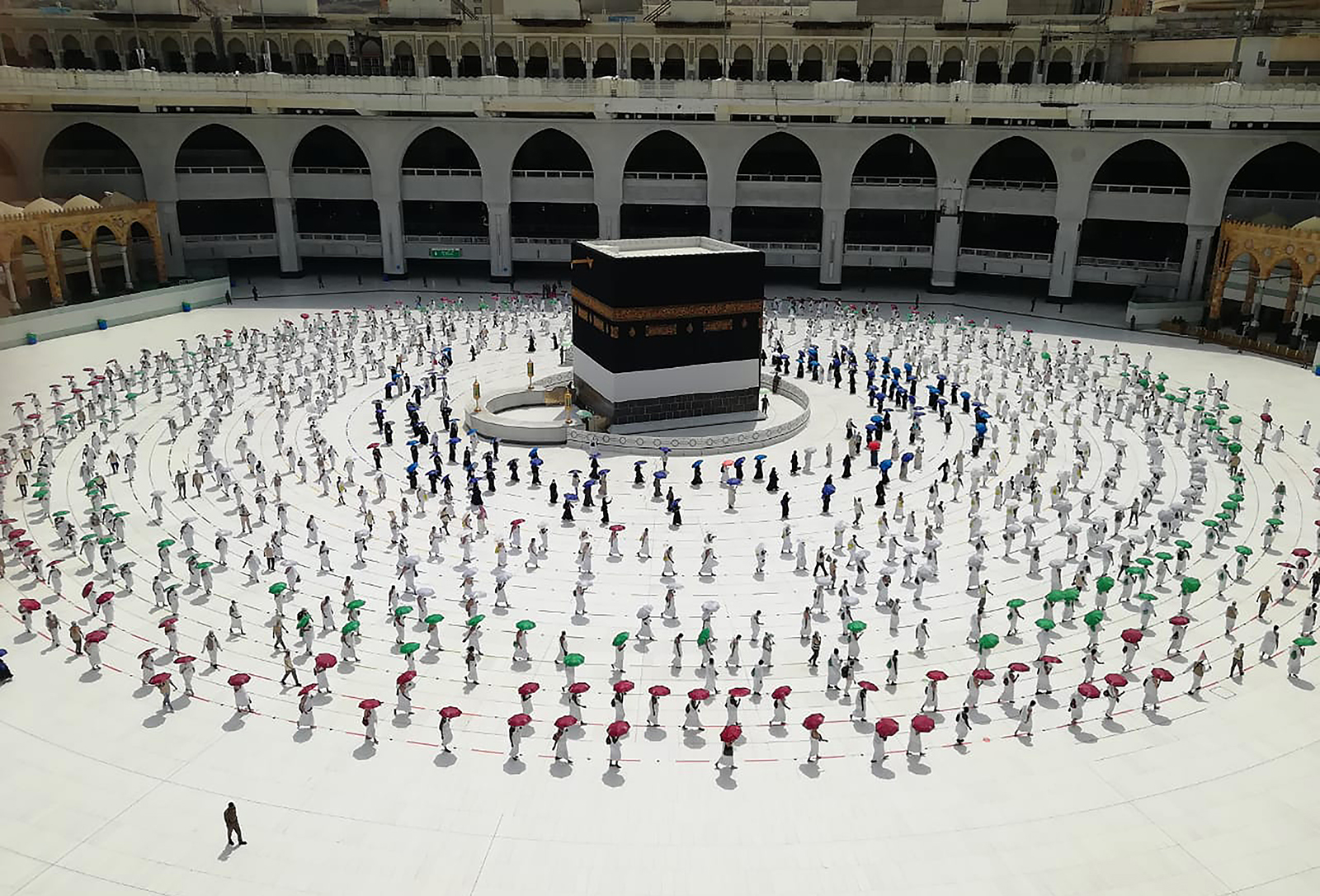

Hundreds of Muslim pilgrims circle the Kaaba, the cubic building at the Grand Mosque, as they observe social distancing to protect against the coronavirus, in the Muslim holy city of Mecca, Saudi Arabia, on July 29, 2020. (AP Photo)

But there are still difficulties for street traders. For many years the government had an unwritten policy of tolerance toward these communities, but deportations dramatically increased a few years ago. In 2017, a campaign called “Nation Without Violators” was launched as part of a new economic agenda.

Mariam’s mother, who has been selling scarves to pilgrims for 15 years, says it has become increasingly risky since then.

“We would sometimes just leave our things and run away if we saw police coming to check,” she said. “It has always been illegal to sell if you don’t have a proper shop. But if you are illegal yourself, then you don’t just get a fine. You go to jail and then are sent back to your own country.”

The risk was worthwhile during Ramadan and hajj seasons especially, when the millions of pilgrims brought a lot of blessings, she said. Then, the pandemic happened and everything changed.

“The past two years, I have been home. I have not been able to make any money at all,” she said. “But neither was anyone else. Not even the big businesses and markets. It is like God cursed them for making it so difficult for us.”

Many businesses across the city never recovered from the months of lockdowns and absence of pilgrims and closed permanently.

A closed-down market sits idle during the month of Ramadan in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, in April 2022. Pandemic travel restrictions have deeply hurt the tourist industry. Photo by Rabiya Jaffery

Khaleel Rehman, one of more than 11 million legal immigrants in the country, has a small shop not far from where Mariam and her mom sat where he sells prayer beads, henna and a wide selection of toys and souvenirs. After shuttering the shop for nearly two years he is selling stock he put away in 2020 when the first lockdown began.

Rehman, born in southern India, has been working in Saudi Arabia for the past 23 years, 20 of them spent running his shop. But before the pilgrims returned he took odd jobs, such as driving for rich locals.

Like others in the city, he hopes the pilgrimage industry will finally fully recover as restrictions ease. “Before, we would make more in hajj two weeks than in three regular months combined. Ramadan is also three times a normal month. I hope this is possible again.”

Abdulrehman Kuraishi, a 21-year-old Saudi, said pilgrimage hospitality runs in his blood. His grandfather owned a date farm and for years pilgrims would take the dates home as gifts. His father is now a distributor of imported food products to grocery chains in Mecca. During Ramadan and hajj, said the son, “we collect the dates and distribute them for free to pilgrims and poorer neighborhoods. I don’t think the spirit of Ramadan overall is fully back but it is much better than 2020.”

He is currently interning in his father’s company as they prepare for the million additional people that will be buying food for the two weeks of hajj.

RELATED: Centro Islámico, a hub for Latino Muslims near and far, breaks ground on expansion during Ramadan

But like his father, Kuraishi hopes to leave the family business to pursue opportunity in the growing demands of technology in Saudi Arabia’s pilgrimage sector.

“I think how to cater to pilgrims evolves with time but people of Mecca will always find prosperity,” he said. “My mother says that Prophet Ibrahim (Abraham) prayed for Mecca to always be blessed. I believe that is true.”

But often for migrants of Mecca, like Mariam’s mother and Rehman, the city’s blessings are a little harder to reap.