The Supreme Court on Monday considered the free speech and religious freedom rights of teachers, coaches and students while hearing a case that could rewrite the rules for prayer in public schools.

During nearly two hours of arguments, the justices debated at what point a private act of faith becomes government endorsement of religion and how far school districts should go to shield young people from potential pressure to engage in religious expression.

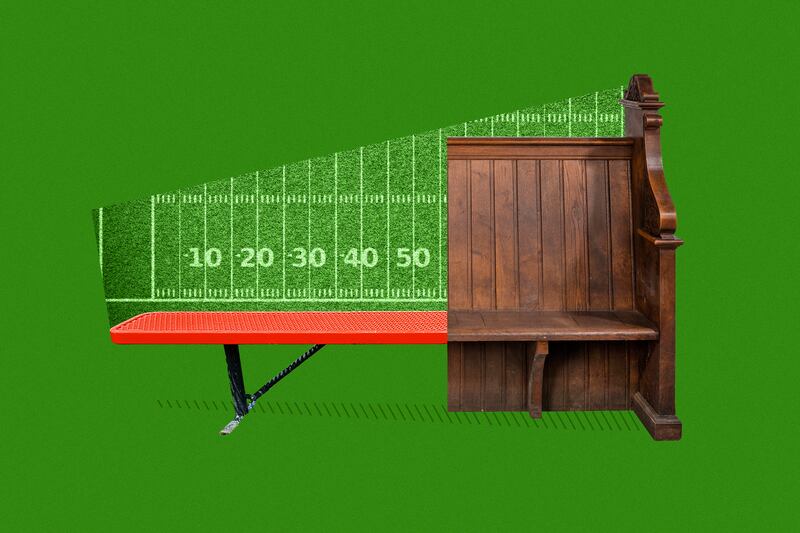

The case, Kennedy v. Bremerton, centers on Joe Kennedy, a football coach who got in trouble for praying at the 50-yard line after games. His former employer, Bremerton School District in Washington state, believes his actions amounted to government, rather than private, speech and unlawfully violated the Constitution’s establishment clause.

Although the justices were asked to consider Kennedy’s specific desire to pray at the 50-yard line, much of Monday’s discussion focused on other, hypothetical scenarios that raise similar legal questions.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor wondered if a classroom teacher could read the Bible or say a prayer just before the bell rings.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh questioned whether a coach could do the sign of the cross before a football game.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett asked about a teacher’s ability to host a youth group meeting in his home.

Justice Clarence Thomas wanted to know if a coach praying on the field and a coach taking a knee during the national anthem should be treated the same.

These hypotheticals — and the attorneys’ responses — illustrated how difficult it can be to articulate a simple and clear legal standard. In the courtroom Monday and in schools across the country each year, stakeholders had and have very different ideas about what the First Amendment allows.

The justices acknowledged this confusion at several points during oral arguments. Some wondered if it was time to do away with past legal standards, such as the “Lemon test,” or offer new guidelines for determining if a school is unlawfully forcing its students to participate in religious acts.

Past rulings on prayer in schools have generally focused on the concept of coercion, with judges aiming to discern whether students are being pressured to participate in a religious activity. Due to coercion concerns, the Supreme Court in recent decades has ruled against prayers offered from the stage at graduation ceremonies and prayers offered over the loud speaker at school football games.

However, the conversation during Monday’s hearing showed that defining coercion is trickier than it seems. The justices and attorneys for both sides agreed that a football coach cannot compel his players to pray with him or show any sort of favoritism to students who share his faith. But they differed on whether praying alone in young people’s presence and allowing them to join if they want to raises the same concerns.

Richard B. Katskee, who argued on behalf of Bremerton School District, said the court should focus on the fact that young players are willing to do almost anything to stay in the good graces of their coach. Under those conditions, even subtle pressure to participate in a postgame prayer is legally significant, he said.

“Students can reasonably understand that you have to go along to get along,” Katskee said.

The attorney for the coach, on the other hand, argued that coercion shouldn’t encompass every activity that students might take it upon themselves to mimic. Under such a standard, a coach wouldn’t be able to wear a jersey for his favorite NFL team or have ashes on his forehead on Ash Wednesday, Paul B. Clement said.

If the focus is on outlawing activities that students could copy to curry favor, “that’s a recipe for no free speech rights at all,” he said.

Clement, Katskee and the justices also debated what counts as government speech. Clement asserted that Kennedy’s prayers were private acts that just happened to take place on the field. Katskee argued that a reasonable observer would believe the coach’s actions were supported by the school and that, therefore, officials were right to intervene.

Looming over this discussion and others was the fact that the two sides don’t agree on the scope of the situation the court should address. Clement wants the eventual ruling to focus on Kennedy’s quiet, quick and individual prayers, while Katskee repeatedly emphasized that the coach had offered vocal group prayers in the past and encouraged other people to join him on the field.

At the district and circuit court level, judges agreed that those additional details mattered, and ruled that the on-field prayers were a public demonstration rather than a private religious act. On Monday, the Supreme Court’s more liberal justices appeared interested in upholding the school district’s lower court wins.

“I don’t know of any ... religion that requires you to go to the 50-yard line to pray,” Sotomayor said.

Many of the more conservative justices, by contrast, seemed to embrace the coach’s version of events.

“I don’t see why the court couldn’t say (past school prayer rulings) logically apply to the locker room and huddle, but they’re not going to extend beyond that,” Kavanaugh said.

The court’s decision in Kennedy v. Bremerton is expected by early July.

alt=Kelsey Dallas

alt=Kelsey Dallas