Should Courts Assess the Sincerity of Religious Beliefs?

Judges have a tendency to be too credulous when it comes to matters of faith.

It was no surprise back in March when the Supreme Court ruled that Texas had to oblige a death-row inmate’s wish for the company of a pastor who would pray with him and touch him as the lethal cocktail dripped into his veins. Such execution-chamber companionship was “part of my faith,” the inmate claimed, and if anything could penetrate the Court’s wall of indifference toward the death penalty, it figured to be religion. The vote was 8–1.

But there was in fact something unexpected about the decision in Ramirez v. Collier: The lone dissenter was Clarence Thomas. Furthermore, Justice Thomas got it right.

Although I don’t often find myself in agreement with Justice Thomas, I have been hoping for a dissenting opinion like his as I’ve watched the Supreme Court’s majority nurture an expanding theocracy that seems to have no stopping point. Justice Thomas is usually an avid part of that majority. This time, however, he ventured where I can’t remember any other justice, liberal or conservative, having the nerve to go: He questioned a religious claimant’s sincerity. His colleagues had granted relief, he complained, “for a demonstrably abusive and insincere claim filed by a prisoner with an established history of seeking unjustified delay.”

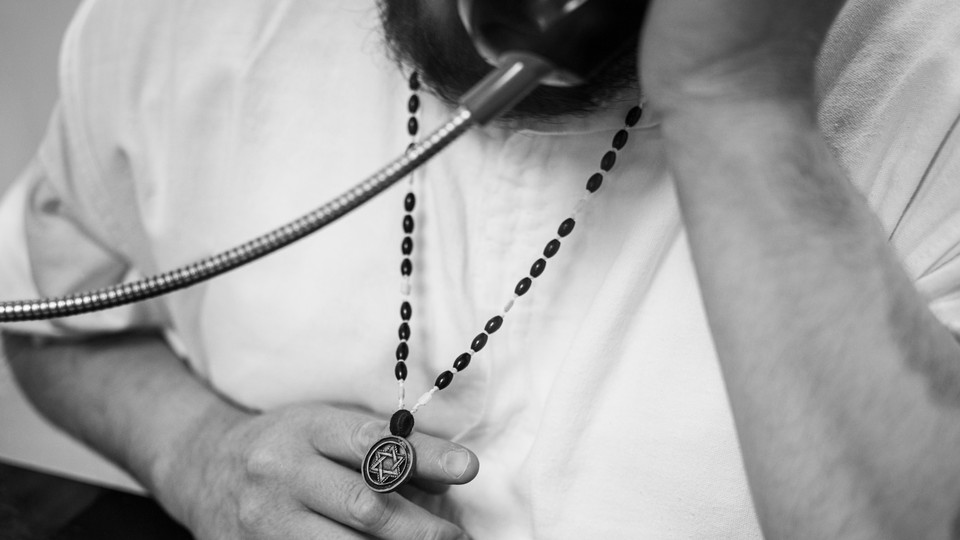

Why did Justice Thomas, of all people, jump off the theocratic bus? Perhaps he was just reacting to the facts of this case: John Ramirez, sentenced to death for murdering a father of nine in a robbery that netted him $1.25, made a series of escalating demands as his execution date approached, first for his pastor’s simple presence, though he at that point disclaimed any desire for touch; then for a laying on of hands; and then, 17 days before his scheduled execution, for audible prayer.

Chief Justice John Roberts, who wrote that Ramirez had displayed “ample” sincerity, offered a history lesson in his majority opinion. He traced the pedigree for pastoral comfort during executions, offered by George Washington to condemned prisoners during the American Revolution, by the federal government to the conspirators in Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, and by the post–World War II Army to Nazis hanged for their crimes.

Justice Thomas was not impressed. “Whether Ramirez’s supposed belief is ‘traditional’ is irrelevant,” he wrote. “The relevant issue is whether Ramirez himself actually believes that it is part of his faith to have his spiritual advisor lay hands on him.” The evidence, Justice Thomas concluded, “cuts strongly in favor of finding that Ramirez is insincere.”

Whether Justice Thomas intended to make a larger point, beyond the confines of this case, about the role of sincerity in evaluating religious claims for special treatment is irrelevant as well. What matters is that he put into play an issue that both liberal and conservative judges have too willingly overlooked for too long.

Why the sincerity of a religious claim should even matter may not be self-evident. Isn’t religious freedom a value in itself, and suppression of religion by the government an offense, whether to millions of believers or a handful, or even to nonbelievers? After all, on the chaotic night in January 2017 when the newly inaugurated Donald Trump imposed his travel ban targeting a set of predominately Muslim countries, the protesters around the country who showed up at airports and town squares and campus quads to oppose a government policy that fell most heavily on members of one religion were standing up for a basic principle of religious freedom that is central to this country’s ideals.

Where sincerity is relevant, where it bites, is when someone seeks a religion-based exception from a rule that applies to society at large and that exception causes harm to someone else. It is this prospect of third-party harm—a price to be paid, a burden to be borne—that makes the question of sincerity necessary. If others are to pay a price for someone’s religious freedom, it’s surely reasonable to expect that the claim is based on felt necessity, not convenience or simple preference.

Sometimes the price is diffuse, falling on taxpayers as a whole and figuring to matter little to any of them. When a federal appeals court ruled last year that the Michigan prison system had to serve two Jewish inmates a slice of cheesecake on the holiday of Shavuot, it accorded sincerity to their claim that eating cheesecake was a matter of religious significance and held that the impact on the system’s $39 million food budget was too trivial to constitute a countervailing “compelling interest” for the state.

But sometimes an accommodation has real victims. The Supreme Court’s 2014 decision in the Hobby Lobby case enabled corporate owners with religious objections to certain contraceptives (which they incorrectly believed caused abortions) to escape compliance with the Affordable Care Act’s mandate to cover birth control in their employee health plans. As a result, thousands of women have been deprived of the free access to contraception that federal law entitles them to—as many as 126,400 women, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg observed in a 2020 dissenting opinion in a subsequent chapter of this long-running dispute. (The harm that Justice Thomas discerned in the Ramirez case was the distress caused to the murder victim’s family by further delay in carrying out a lawful sentence; Ramirez was not challenging his death sentence but rather the circumstances under which it would be carried out. The majority opinion in his case made new law. In another execution-chamber case from Texas only three years ago, a Buddhist inmate claimed discrimination because Texas permitted the presence of only Christian and Muslim clergy. The Court ruled then that the state had to choose between permitting clergy of all faiths or barring clergy completely. By contrast, the Court in the Ramirez case treated the presence of clergy as an inmate’s affirmative right.)

The Christian family that owns the Hobby Lobby chain claimed that complying with the law would make them complicit in sin. Neither the Obama administration nor the justices on either side of the 5–4 decision challenged the owners’ sincerity. Rather, the two sides battled over whether the Religious Freedom Restoration Act entitled them to relief. That 1993 law provides that the government “shall not substantially burden a person’s exercise of religion” unless it can justify the burden as serving a “compelling interest” by the “least restrictive means.” Justice Samuel Alito’s majority opinion held that the Obama administration had less burdensome ways to enable women’s access to birth control. (This proved, perhaps foreseeably, not to be the case.) Justice Ginsburg argued in dissent that the requirement should not be seen as a substantial burden on Hobby Lobby at all, because the link between providing the coverage and any individual woman’s decision to use a particular contraceptive was too remote to count.

What no one challenged was the family’s belief that the emergency contraceptives to which they objected interrupted the development of a fertilized egg and thus caused what in their view was an abortion. In fact, there could be no fertilized egg, because these medications actually work by preventing ovulation in the first place. It was unfortunate but not surprising that the owners’ contrary belief went unchallenged. A long tradition deters judges from questioning the basis for someone’s religious belief, largely for good reason. Judges are hardly competent to assess the doctrinal validity of someone’s belief, and would undoubtedly violate the First Amendment’s establishment clause by getting into the business of approving some beliefs as valid while rejecting others. It would have been refreshing had the judges of the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit declared, accurately, that although eating a dairy meal on Shavuot is customary, nothing in Jewish law requires consuming cheesecake in particular for the holiday, but it was understandable that they refrained. Perhaps they were tempted; the opinion reads like a shrug and a resigned sigh of “whatever” rendered in legal rhetoric.

In producing its risible result, the Sixth Circuit went wrong not in failing to interrogate Jewish law but in accepting, against substantial evidence to the contrary, the sincerity of the two inmates who went to federal court with their cheesecake claim. The inmates invoked the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act, a federal law enacted in 2000 as an enhancement to the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. The statutory language, referring to “any exercise of religion, whether or not compelled by, or central to, a system of religious belief,” makes it clear that just about anything can count as religion. It is judges’ inability to question religion itself—the basis for someone’s belief—that makes the sincerity question so important. As Nathan S. Chapman of the University of Georgia School of Law wrote in an article that Justice Thomas cited in his Ramirez dissent, “The government may not distribute benefits and burdens on the basis of religious truth, but it can be difficult to distinguish between whether a religious claim is ‘true’ and whether the claimant ‘truly’ believes it.” Understandably, as a result courts tend to merge the sincerity question into the hands-off question of religious belief itself, and punt on both.

That merger was evident in the recent Supreme Court argument in Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, the “praying coach” case in which a high-school football coach claims the right to kneel and pray audibly on the 50-yard line at the conclusion of the game. The coach, Joseph Kennedy, lost his job for insisting that he needed to perform his personal ritual in public despite the school’s offer of several other locations for private prayer. During the argument, Justice Sonia Sotomayor observed to the coach’s lawyer, Paul Clement: “I don’t know of any other religion that requires you to get at the 50-yard line, the place where post-game victory speeches are given. What religion requires you to do it at that spot?”

Clement replied, “So the coach’s religion, and he felt—and nobody’s questioned the sincerity of his religious beliefs—” Justice Sotomayor interrupted: “That he had to thank God. But why there?”

“He felt compelled to make his prayer there,” the lawyer replied. “What’s driving the religious exercise is that’s where the event that the religious adherent is thankful for took place.”

For the remainder of the argument, there were plenty of questions about the constitutional implications of the standoff between the coach and his employer, but none about the sincerity of his claim that his behavior was religiously compelled.

Chapman argues in his article that “sincerity is a question of fact,” one that judges should evaluate “just as they would any other mental state,” with attention to “evidence of ulterior motive, personal inconsistency, and idiosyncrasy.” Published in 2017, his article predates what is perhaps the most head-spinning invocation of religious liberty: the current flood of religion-based challenges to COVID-19-vaccine requirements.

Earlier this year, a federal district judge in Texas, Reed O’Connor, ruled in favor of 26 Navy SEALs with a variety of religious objections to the Navy’s requirement that they be vaccinated. Judge O’Connor, an appointee of President George W. Bush who has devoted his career to blocking the policy initiatives of Democratic presidents, specified the SEALs’ vaccine objections: “(1) opposition to abortion and the use of aborted fetal cell lines in development of the vaccine; (2) belief that modifying one’s body is an affront to the Creator; (3) direct, divine instruction not to receive the vaccine; and (4) opposition to injecting trace amounts of animal cells into one’s body.” To the judge, no further inquiry was necessary. In a classic merger of the questions of sincerity and faith, he wrote: “Plaintiffs’ beliefs about the vaccine are undisputedly sincere, and it is not the role of this court to determine their truthfulness or accuracy.”

Though O’Connor’s own faith in human nature may be heartwarming, there is an obvious way to test the sincerity of religious vaccine resisters who claim abhorrence of the vaccine’s origins. Do they use any of the common medications that also derive from research using fetal cells, including Tylenol, Pepto Bismol, ordinary aspirin, Sudafed, Preparation H, and dozens of others? A hospital system in Arkansas that requires health workers to be vaccinated listed 30 such drugs and required those requesting a religious exemption because of the fetal-cell issue to sign a form pledging not to use “any of the medications listed as examples or any other medication (prescription, vaccine, or over the counter medication) that has used fetal cell lines in their development or testing.”

The Supreme Court put O’Connor’s ruling on hold over the vigorous dissent of Justices Alito and Neil Gorsuch, who asserted that the SEALs had a valid constitutional claim under the free-exercise clause. The Court’s order came on March 25, the day after the 8–1 decision in the Ramirez case. Justice Alito sounded almost as if he’d had second thoughts about not having joined Justice Thomas’s dissent. “Ramirez was less than punctilious and consistent in requesting a religious accommodation, but the Court’s decision forgave all that,” Alito wrote in his dissent from the Navy SEALs order. “The contrast between our decision in Ramirez yesterday and the Court’s treatment of respondents today is striking.” Because the Court’s order itself was unsigned and unexplained, there is no way of knowing whether the seven other justices regarded the SEALs’ claims as too preposterous to credit or, more likely, that the Court deferred to the government’s assertion of military necessity.

Meanwhile, the SEALs presumably remain unvaccinated, choosing instead to be undeployable under Navy regulations. The Jewish inmates in Michigan will presumably have their cheesecake on Shavuot, which begins this year at nightfall on June 4. Ramirez’s story, however, has something of an O. Henry ending. The judge who presided over his original trial set a new execution date of October 5, 2022. But on April 14, the district attorney of Nueces County, where the judge sits, filed a motion to withdraw the death warrant on the ground that “the death penalty is unethical and should not be imposed on Mr. Ramirez or any other person.”

The district attorney, Mark Gonzalez, a Democrat serving in an elected post, had issued three previous death warrants for Ramirez. In a Facebook Live broadcast, he explained that he had long struggled with the death penalty and had finally changed his mind about it. “I did this because I thought this would be the right thing to do,” he said.

He sounded sincere.