.

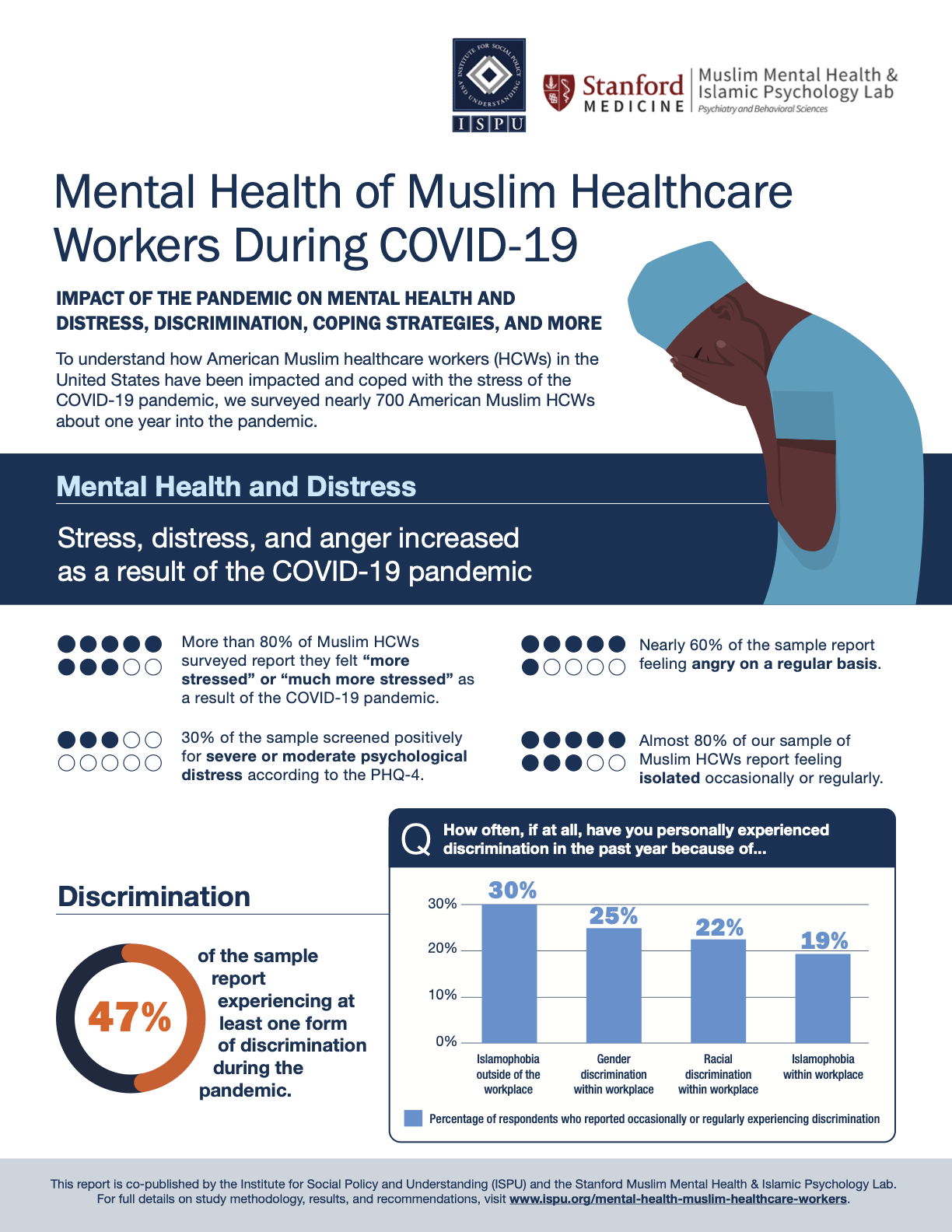

Mental Health of Muslim Healthcare Workers During COVID-19

APRIL 20, 2022 | BY DR. RANIA AWAAD, KAMAL SULEIMAN, DALIA MOGAHED, DR. LANA ABDOLE, ALIZAH ALI, AND NOUR HAMMAMI

SUMMARY

To understand how American Muslim healthcare workers (HCWs) in the United States have been impacted by this stress, and how they have coped with it, this study surveyed nearly 700 American Muslim HCWs about one year into the pandemic. Results include the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and religious and racial discrimination on mental health, as well as an investigation into “healthy” and “unhealthy” coping strategies.

This report is co-published by the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding (ISPU) and the Stanford Muslim Mental Health & Islamic Psychology Lab.

.

Executive Summary

Since the spring of 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted nearly every sphere of life across the world. Healthcare systems, in particular, have been overwhelmed with massive surges of hospitalizations, and the burden of care for the nearly unprecedented volume of patients has fallen on the shoulders of healthcare workers (HCWs). To understand how American Muslim HCWs working in the United States have been impacted by this stress, and how they have been coping with it, this study surveyed nearly 700 American Muslim HCWs about one year into the pandemic. This report reveals that, while the detrimental impact of COVID-related stress and the compounded stress of discrimination was significant, American Muslim HCWs utilized several effective coping strategies, both religious and non-religious in nature.

Impact of COVID on Mental Health and Distress

More than 80% of our study’s sample reported that they felt “more stressed” or “much more stressed” as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, about 30% screened positively for moderate or severe psychological distress according to the PHQ-4 (a short screening scale for anxiety and depression) and nearly 60% of the sample reported feeling angry on a regular basis. Concerningly, almost 80% of our sample reported feeling isolated occasionally or regularly. Given the vital role of factors such as family, community, and work environment to the population of interest to this study, this is particularly worrisome.

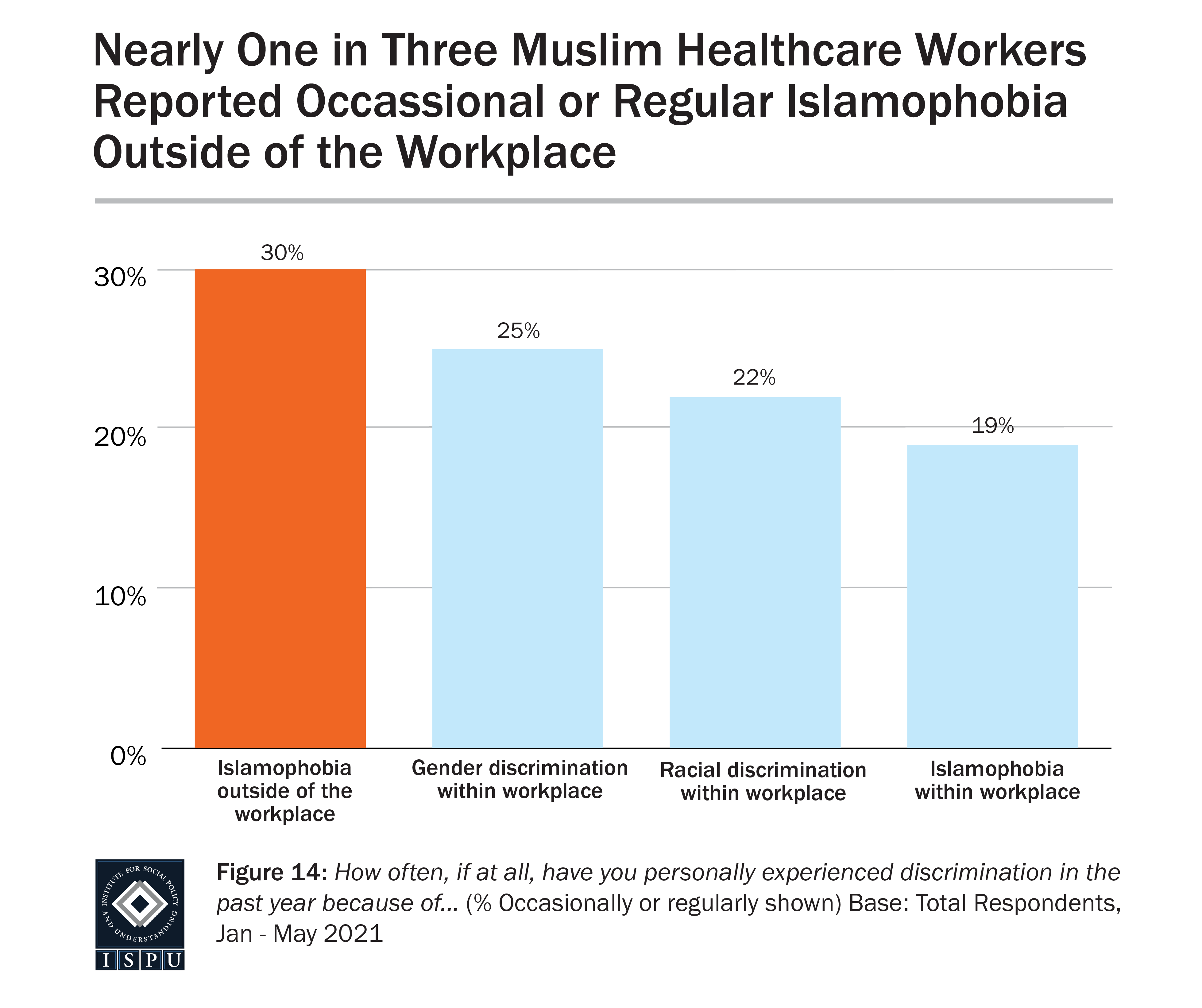

Frequency of Discrimination

Forty-seven percent of the overall sample reported experiencing at least one form of discrimination during the pandemic. Thirty percent of the sample reported experiencing Islamophobia occasionally or regularly outside of the workplace, and 19% reported experiencing Islamophobia within the workplace. In regard to racial discrimination within the workplace, 22% of those surveyed reported occasional or regular incidents. And, 25% reported experiencing gender discrimination within the workplace.

Discrimination Associated with Higher Risk of Psychological Distress, Including Depression and Anxiety

Our multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that those HCWs who reported experiencing occasional or regular Islamophobia outside of the workplace in addition to racial discrimination within the workplace, compared to those who experienced no discrimination, had five times higher risk of mild psychological distress, and 6.6 times higher risk of moderate or severe psychological distress. HCWs experiencing occasional or regular discrimination of mixed forms (racial, gender, or religious), compared to those who experienced no discrimination, had five times higher risk of mild distress, and nine times higher risk of moderate or severe distress. This information is particularly concerning given that, in the absence of strong protective factors, these outcomes could be even further exacerbated. This sample, as discussed later in this report, utilized a number of widely protective coping strategies at a high rate, leading to the question of how HCWs who do not partake in those protective strategies may be even further impacted by experiences of discrimination.

Islamophobia in the Workplace Associated with Increased Healthy Coping Strategies, Particularly Those of a Religious Nature

We also found that those who reported experiencing Islamophobia within the workplace utilized a higher number of healthy coping strategies, particularly religious healthy coping strategies. Additionally, they were found to adopt fewer unhealthy coping strategies (more details on coping strategies will follow). It may be surprising that those who experienced Islamophobia were also more likely to use healthy coping strategies, given the detrimental effect of discrimination on the overall mental health of our participants. However, in light of existing research which shows that those who perceive Islamophobia tend to also view their religion as a more important part of their life, there may be a way to make sense of this finding.

Racial Discrimination in the Workplace Associated with Less Healthy Coping and More Unhealthy Coping

In contrast to the above finding, those healthcare workers who reported racial discrimination in the workplace were less likely to utilize healthy coping strategies and more likely to utilize unhealthy religious coping strategies. This finding raises several important questions, discussed further in the body of the report. Presently, our analysis cannot make conclusions about the cause of these paradoxical findings, but it illustrates that experiences of racial discrimination among our sample are linked with different patterns of coping compared to religious discrimination in the workplace. Continued research into the nuances of identity, discrimination, and stress response is definitely warranted to understand what may be at the root of this difference.

Most Common Coping Strategies

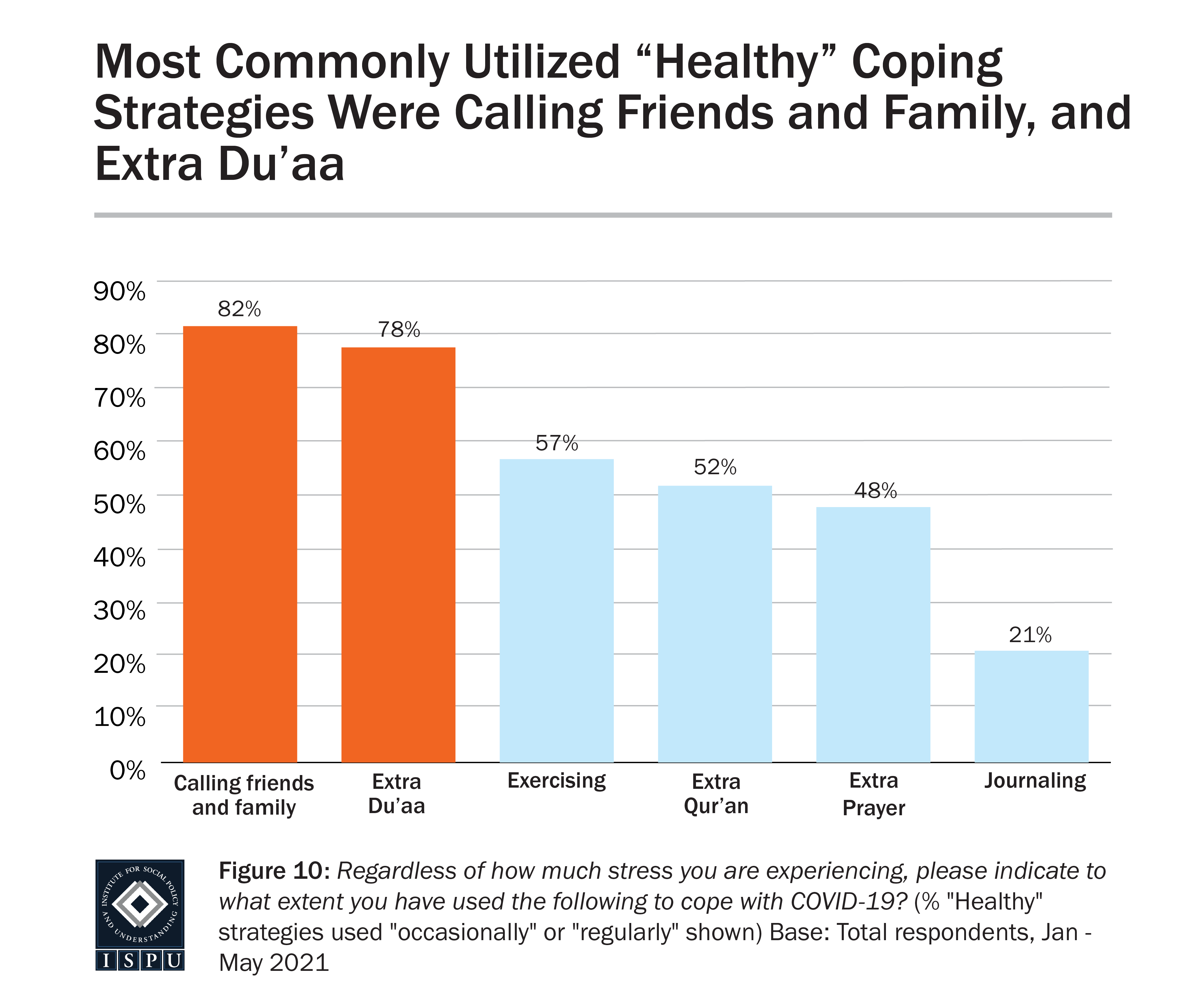

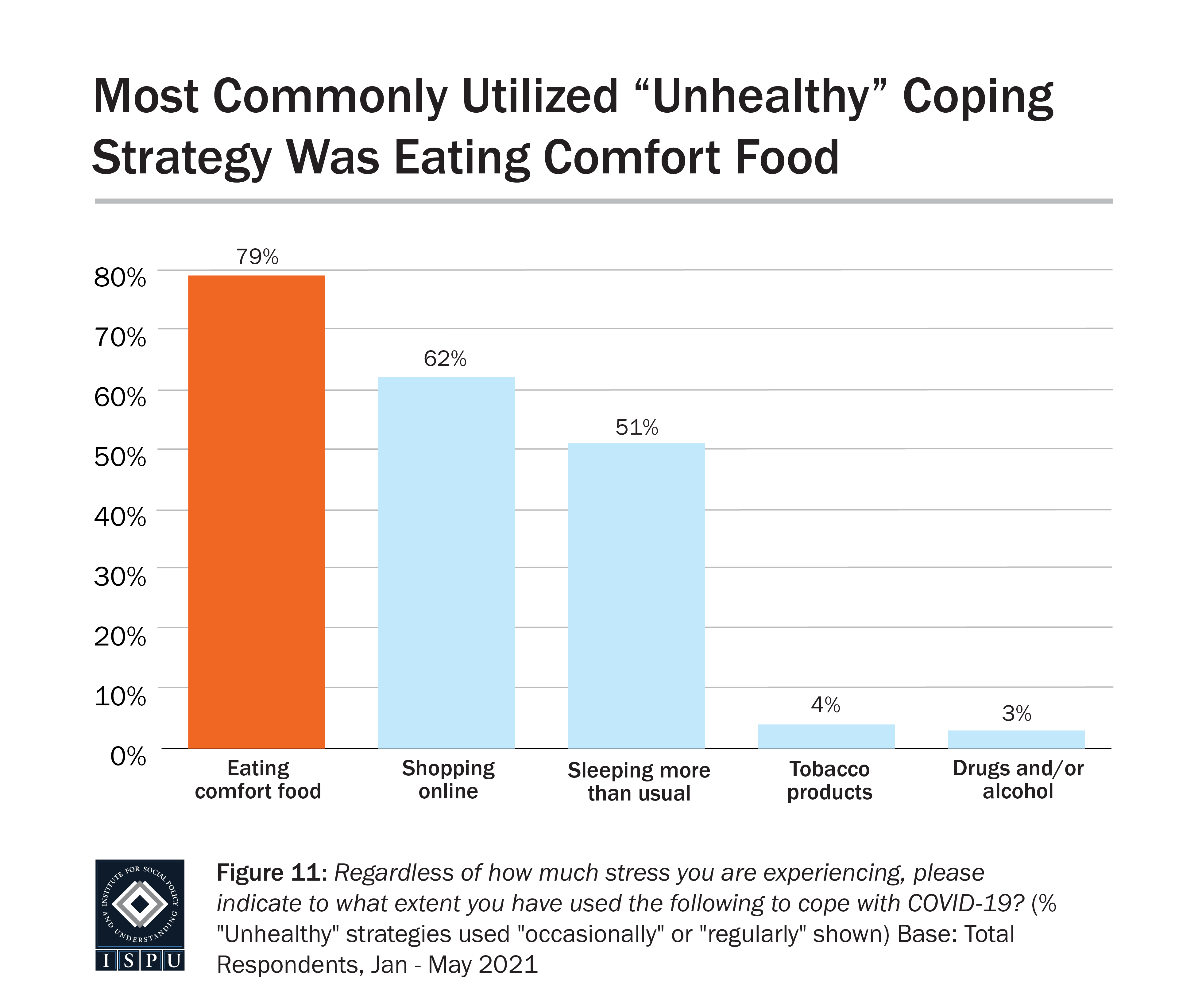

A coping strategy can be defined as a behavior a person partakes in or a belief a person relies on when dealing with stress, whether consciously or unconsciously, as an attempt to relieve their negative emotions. Our survey investigated numerous behavioral and cognitive coping strategies (see “Coping Strategies” for a comprehensive list). The most commonly used coping strategy reported in our sample was calling friends and family, with 82% of the sample reporting doing so occasionally or regularly. This demonstrates that this sample of American Muslim HCWs often leaned on their social support networks to help cope with pandemic-related stress. In our sample, the other most commonly utilized non-religious coping strategies were eating comfort food (79%), shopping online (62%), exercising (57%), and sleeping more than usual (51%). Religious coping strategies were used much more commonly than non-religious strategies as a whole, but extra du’aa (prayer of supplication or invocation) was particularly common (78%).

Some Coping Strategies Linked with Increased Risk of Distress

There are some coping strategies thought to be maladaptive, which have been linked to high psychological distress and lower overall mental health; this is in contrast with positive, or adaptive, coping strategies that can successfully relieve negative emotion and promote well-being (Mong & Noguchi, 2021). Some of these maladaptive, or unhealthy, coping strategies were observed in our sample, such as eating comfort food (79%), shopping online (62%), or sleeping more than usual (51%). Using multiple logistic regression analyses, all of these strategies had significant associations with poorer mental health, each being linked to more than two times increased risk of moderate to severe psychological distress as measured by the PHQ-4.

Feeling Angry with Allah was Strongly Linked to Feeling a General Sense of Anger on a Regular Basis and Risk for Depression

Muslim healthcare workers who reported thoughts of feeling angry with Allah were more than eight times more likely to also report feeling a general sense of anger on a regular basis. This reveals an opportunity for future research to investigate a potential link between anger inspired by environmental factors such as the pandemic and anger directed toward metaphysical/spiritual beliefs; however, our study alone cannot infer a link between these factors. Nevertheless, given the importance of religious beliefs and practices reported by our study’s sample, and the role of religious coping strategies highlighted in both our analyses and those of previous literature, the implications are significant for how American Muslim HCWs will be able to lean on their most effective methods of coping with stress.

Remembering Blessings and Thanking Allah was Widely Protective

In our study, those who reported trying to remember their blessings and thank Allah were at a significantly reduced risk for psychological distress, after controlling for other coping strategies, race, gender, and age. This was the most protective religious coping strategy revealed within our sample. American Muslim HCWs from our study reported utilizing gratefulness at a high rate (93%), indicating that this was a commonly held value. The protective impact of this strategy, on top of expansive existing literature about the positive impact of gratefulness, points to another major strength among American Muslim HCWs. Alongside our finding about calling friends and family (used by over 80% of participants), our study reveals a strong tendency for American Muslim HCWs to utilize healthy coping strategies that are well-supported by existing evidence. These strategies can be capitalized on and encouraged among American Muslim HCWs to further protect against the stresses of their role, particularly amidst a pandemic.

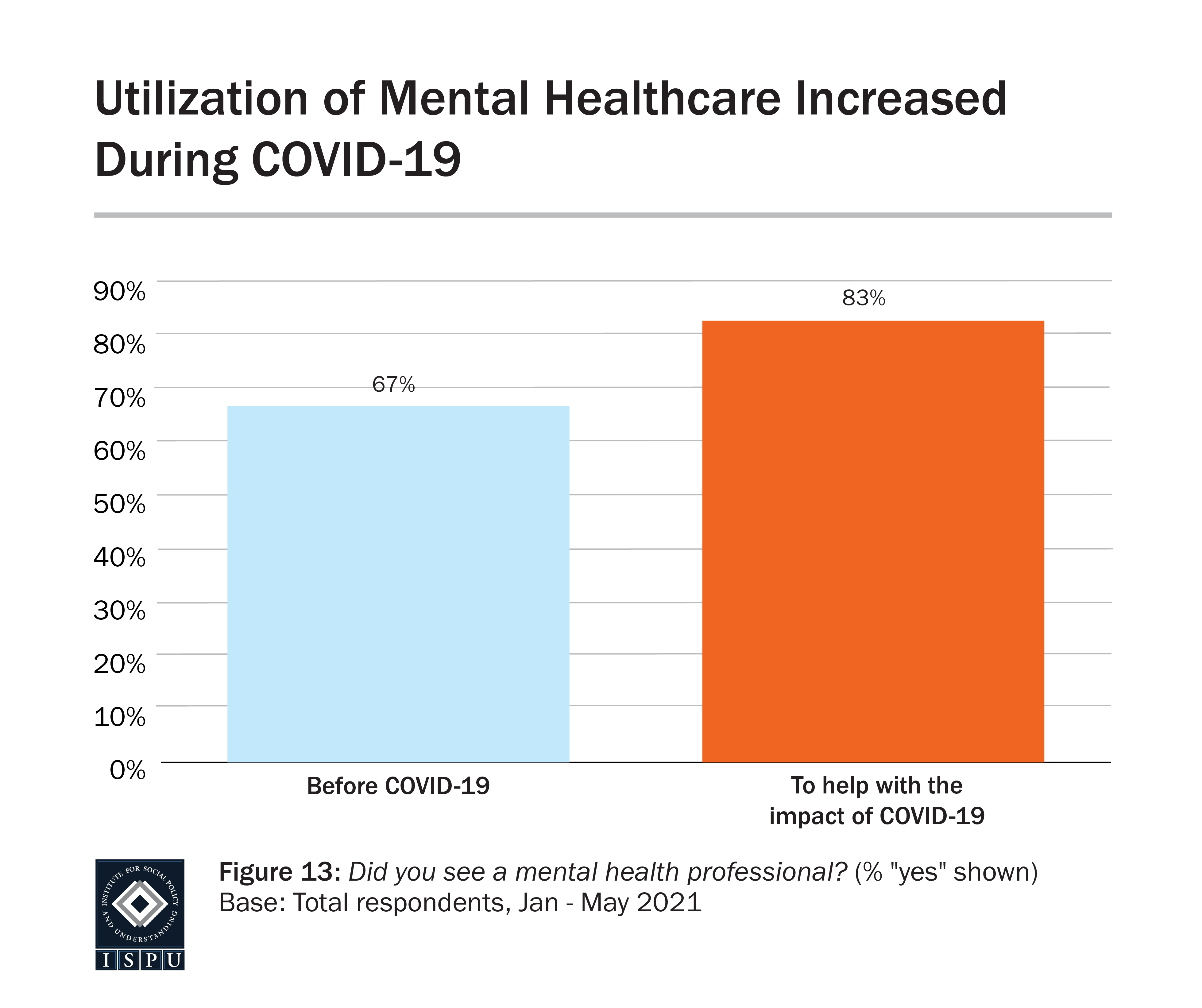

Seeing a Mental Health Professional During the Pandemic was Widely Protective

Eighty-three percent of our sample reported seeing a mental health professional “to help with the impact of COVID-19.” This is a very high proportion, particularly given previous evidence that western Muslims overall have underutilized mental healthcare (Zia et al., 2013). Additionally, our regression analysis found that seeing a mental health professional during the pandemic was determined to be protective against feeling angry, screening positively for depression, anxiety, and mild and moderate psychological distress. It is hoped that our sample was able to demonstrate the efficacy of utilizing professional help to cope with the impact of COVID-19; this may provide evidence for other populations within the Muslim community that seeking mental healthcare is beneficial.

SUMMARY

To understand how American Muslim healthcare workers in the United States have been impacted by this stress, and how they have coped with it, this study surveyed nearly 700 American Muslim HCWs about one year into the pandemic. Results include the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, religious, and racial discrimination on mental health, as well as an investigation into healthy and unhealthy coping strategies.

This report is co-published by the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding (ISPU) and the Stanford Muslim Mental Health & Islamic Psychology Lab.

DOWNLOADS

Executive Summary

Since the spring of 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted nearly every sphere of life across the world. Healthcare systems, in particular, have been overwhelmed with massive surges of hospitalizations, and the burden of care for the nearly unprecedented volume of patients has fallen on the shoulders of healthcare workers (HCWs). To understand how American Muslim HCWs working in the United States have been impacted by this stress, and how they have been coping with it, this study surveyed nearly 700 American Muslim HCWs about one year into the pandemic. This report reveals that, while the detrimental impact of COVID-related stress and the compounded stress of discrimination was significant, American Muslim HCWs utilized several effective coping strategies, both religious and non-religious in nature.

Impact of COVID on Mental Health and Distress

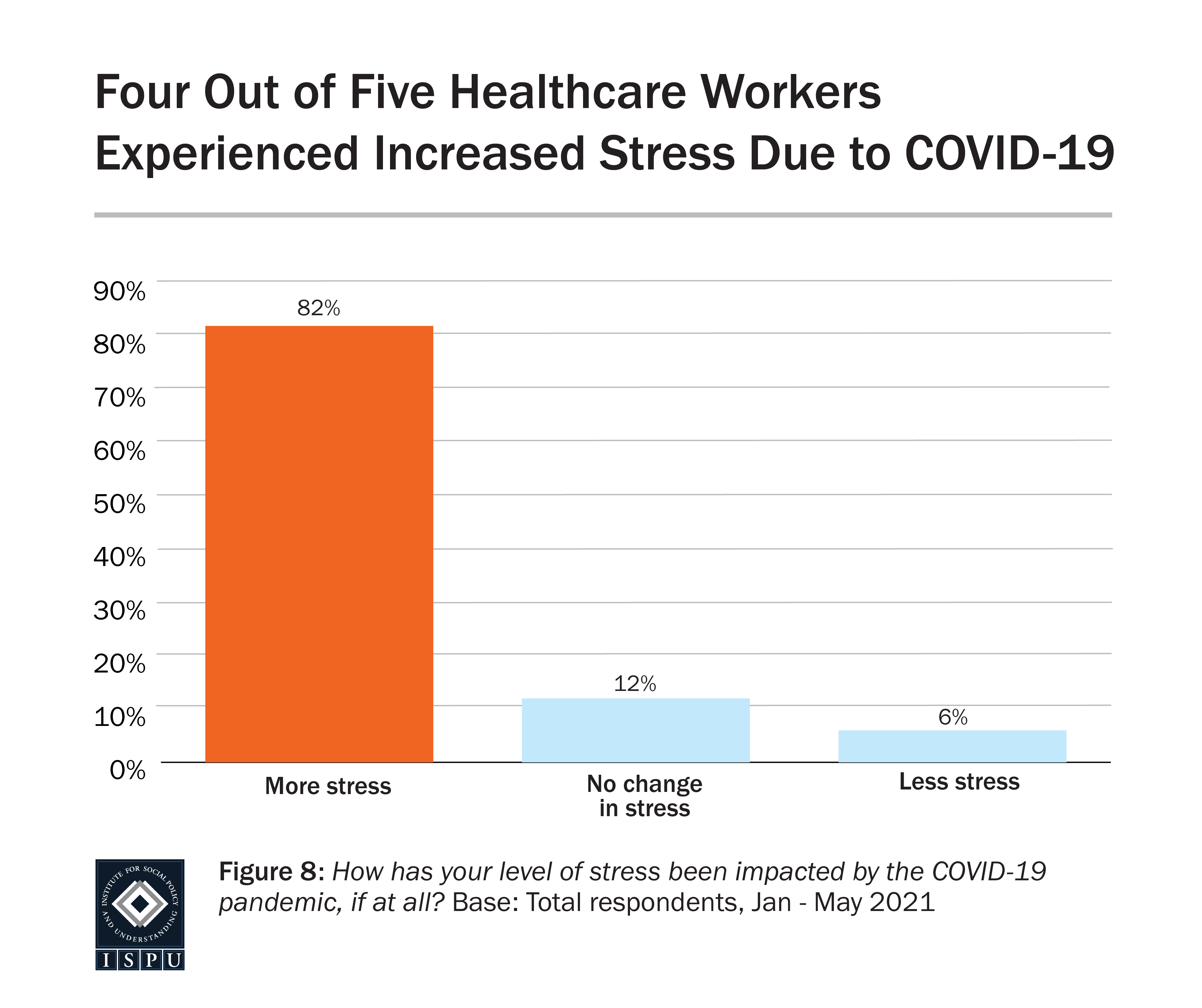

More than 80% of our study’s sample reported that they felt “more stressed” or “much more stressed” as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, about 30% screened positively for moderate or severe psychological distress according to the PHQ-4, and nearly 60% of the sample reported feeling angry on a regular basis. Concerningly, almost 80% of our sample reported feeling isolated occasionally or regularly. Given the vital role of factors such as family, community, and work environment to the population of interest to this study, this is particularly worrisome.

Frequency of Discrimination

Forty-seven percent of the overall sample reported experiencing at least one form of discrimination during the pandemic. Thirty percent of the sample reported experiencing Islamophobia occasionally or regularly outside of the workplace, and 19% reported experiencing Islamophobia within the workplace. In regard to racial discrimination within the workplace, 22% of those surveyed reported occasional or regular incidents. And, 25% reported experiencing gender discrimination within the workplace.

Discrimination Associated with Higher Risk of Psychological Distress, Including Depression and Anxiety

Our multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that those HCWs who reported experiencing occasional or regular Islamophobia outside of the workplace in addition to racial discrimination within the workplace, compared to those who experienced no discrimination, had five times higher risk of mild psychological distress, and 6.6 times higher risk of moderate or severe psychological distress. HCWs experiencing occasional or regular discrimination of mixed forms (racial, gender, or religious), compared to those who experienced no discrimination, had five times higher risk of mild distress, and nine times higher risk of moderate or severe distress. This information is particularly concerning given that, in the absence of strong protective factors, these outcomes could be even further exacerbated. This sample, as discussed later in this report, utilized a number of widely protective coping strategies at a high rate, leading to the question of how HCWs who do not partake in those protective strategies may be even further impacted by experiences of discrimination.

Islamophobia in the Workplace Associated with Increased Healthy Coping Strategies, Particularly Those of a Religious Nature

We also found that those who reported experiencing Islamophobia within the workplace utilized a higher number of healthy coping strategies, particularly religious healthy coping strategies. Additionally, they were found to adopt fewer unhealthy coping strategies (more details on coping strategies will follow). It may be surprising that those who experienced Islamophobia were also more likely to use healthy coping strategies, given the detrimental effect of discrimination on the overall mental health of our participants. However, in light of existing research which shows that those who perceive Islamophobia tend to also view their religion as a more important part of their life, there may be a way to make sense of this finding.

Racial Discrimination in the Workplace Associated with Less Healthy Coping and More Unhealthy Coping

In contrast to the above finding, those healthcare workers who reported racial discrimination in the workplace were less likely to utilize healthy coping strategies and more likely to utilize unhealthy religious coping strategies. This finding raises several important questions, discussed further in the body of the report. Presently, our analysis cannot make conclusions about the cause of these paradoxical findings, but it illustrates that experiences of racial discrimination among our sample are linked with different patterns of coping compared to religious discrimination in the workplace. Continued research into the nuances of identity, discrimination, and stress response is definitely warranted to understand what may be at the root of this difference.

Most Common Coping Strategies

A coping strategy can be defined as a behavior a person partakes in or a belief a person relies on when dealing with stress, whether consciously or unconsciously, as an attempt to relieve their negative emotions. Our survey investigated numerous behavioral and cognitive coping strategies (see “Coping Strategies” for a comprehensive list). The most commonly used coping strategy reported in our sample was calling friends and family, with 82% of the sample reporting doing so occasionally or regularly. This demonstrates that this sample of American Muslim HCWs often leaned on their social support networks to help cope with pandemic-related stress. In our sample, the other most commonly utilized non-religious coping strategies were eating comfort food (79%), shopping online (62%), exercising (57%), and sleeping more than usual (51%). Religious coping strategies were used much more commonly than non-religious strategies as a whole, but extra du’aa (prayer of supplication or invocation) was particularly common (78%).

Some Coping Strategies Linked with Increased Risk of Distress

There are some coping strategies thought to be maladaptive, which have been linked to high psychological distress and lower overall mental health; this is in contrast with positive, or adaptive, coping strategies that can successfully relieve negative emotion and promote well-being (Mong & Noguchi, 2021). Some of these maladaptive, or unhealthy, coping strategies were observed in our sample, such as eating comfort food (79%), shopping online (62%), or sleeping more than usual (51%). Using multiple logistic regression analyses, all of these strategies had significant associations with poorer mental health, each being linked to more than two times increased risk of moderate to severe psychological distress as measured by the PHQ-4.

Feeling Angry with Allah was Strongly Linked to Feeling a General Sense of Anger on a Regular Basis and Risk for Depression

Muslim healthcare workers who reported thoughts of feeling angry with Allah were more than eight times more likely to also report feeling a general sense of anger on a regular basis. This reveals an opportunity for future research to investigate a potential link between anger inspired by environmental factors such as the pandemic and anger directed toward metaphysical/spiritual beliefs; however, our study alone cannot infer a link between these factors. Nevertheless, given the importance of religious beliefs and practices reported by our study’s sample, and the role of religious coping strategies highlighted in both our analyses and those of previous literature, the implications are significant for how American Muslim HCWs will be able to lean on their most effective methods of coping with stress.

Remembering Blessings and Thanking Allah was Widely Protective

In our study, those who reported trying to remember their blessings and thank Allah were at a significantly reduced risk for psychological distress, after controlling for other coping strategies, race, gender, and age. This was the most protective religious coping strategy revealed within our sample. American Muslim HCWs from our study reported utilizing gratefulness at a high rate (93%), indicating that this was a commonly held value. The protective impact of this strategy, on top of expansive existing literature about the positive impact of gratefulness, points to another major strength among American Muslim HCWs. Alongside our finding about calling friends and family (used by over 80% of participants), our study reveals a strong tendency for American Muslim HCWs to utilize healthy coping strategies that are well-supported by existing evidence. These strategies can be capitalized on and encouraged among American Muslim HCWs to further protect against the stresses of their role, particularly amidst a pandemic.

Seeing a Mental Health Professional During the Pandemic was Widely Protective

Eighty-three percent of our sample reported seeing a mental health professional “to help with the impact of COVID-19.” This is a very high proportion, particularly given previous evidence that western Muslims overall have underutilized mental healthcare (Zia et al., 2013). Additionally, our regression analysis found that seeing a mental health professional during the pandemic was determined to be protective against feeling angry, screening positively for depression, anxiety, and mild and moderate psychological distress. It is hoped that our sample was able to demonstrate the efficacy of utilizing professional help to cope with the impact of COVID-19; this may provide evidence for other populations within the Muslim community that seeking mental healthcare is beneficial.

.

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly disrupted the economic, social, and healthcare systems of the world since March 2020. Healthcare systems have faced massive surges of hospitalizations, and the burden of care for the nearly unprecedented volume of patients has fallen on the shoulders of healthcare workers (HCWs). As a consequence of these severe stresses, both the general population and HCWs have been reported to be facing increased anxiety, depression, and distress both in the United States and abroad (Giusti et al., 2020; Xiong et al., 2020). Concerningly, marginalized groups in the United States during the pandemic are reported to be facing compounded distress due to discrimination, both in the general population and among HCWs (Chen et al., 2020; Kantemneni, 2020). This is worrisome given pre-pandemic findings that HCWs of racial, ethnic, and religious minority backgrounds are already prone to experiencing poor mental health due to increased stress and insufficient support in the workplace (Silver, 2019). The interplay of new pandemic-related stressors, discrimination, and existing disparities in the workplace warrants continued research into how HCWs from various backgrounds are reacting to and coping with these unprecedented circumstances.

Little is currently known about American Muslim HCWs in particular, including their current demographic distribution in the healthcare field. One recent study reported that about 4.5% of U.S. physicians were medical graduates from Muslim-majority countries. The proportion of Muslim HCWs in the U.S. healthcare field overall is almost definitely higher, given that this estimate does not include non-physician HCWs, U.S.-born Muslim HCWs, nor Muslim HCWs from non-Muslim-majority countries (Boulet et al., 2020). The sparse existing research on this population has revealed that they face particular stressors in the workplace due to their religious identity. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, social isolation from coworkers post-9/11, additional scrutiny in hiring and residency matching, refusal of care from patients, and implicit biases have led to increased job turnover and a diminished sense of belonging among Muslim providers in the U.S. (Abu-Ras, 2013; Laird, 2013; Padela, 2016). These salient risk factors justify serious concern for the mental health of American Muslim HCWs during the heightened stress and pressure of the COVID-19 pandemic.

To address this gap in knowledge, this study sought to survey American Muslim HCWs’ mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. It also sought to identify how American Muslim HCWs were reacting to, and dealing with, the psychological impact of the pandemic by investigating which forms of coping were being utilized as well as how the utilization of those coping mechanisms was related to mental health outcomes. This study also investigated the impact of four types of discrimination and analyzed how those reported experiences were related to other forms of distress and coping mechanism utilization.

ISPU and the Stanford Muslim Mental Health & Islamic Psychology Lab would like to acknowledge the following partners:

Outreach Consultants

-

- Muslim Wellness Foundation

- Muslim Life Planning Institute

- Masjid Muhammad: The Nation’s Mosque

- The Mosque Cares

Outreach Partners

American Muslim Health Professionals; Association of Muslim Chaplains; British Islamic Medical Association; CAIR-GA; CAIR-SFBA; ICNA Relief; Imamia Medics International; Inner-city Muslim Action Network; Islam in Spanish; Islamic Medical Association of North America (IMANA); Najah Bazzy; Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS)

.

Methods

Ethics approval for human research was granted by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board for this study, which consisted of an online survey disseminated from January 2021 until May 2021 among American Muslims currently working in the healthcare field in the United States. During this time the American healthcare system was experiencing significant strain as a result of a large spike in COVID-19 infections and hospitalizations.

The survey was developed by researchers at the Stanford Muslim Mental Health and Islamic Psychology Lab, and informed consent was obtained prior to each subject’s participation. Survey questions were pulled from existing psychometric scales like the PHQ-4 to measure depression and anxiety and also included new self-report items to measure several demographic factors, stress, experiences of isolation, four types of discrimination, and the use of religious and non-religious behavioral and cognitive coping strategies (Kroenke, 2009). Confidentiality was maintained during data collection and analysis. All participants remain anonymous. The final sample of 692 American Muslim HCWs was collected using convenience sampling across social media platforms (Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook), as well as through numerous professional networks and channels geared toward Muslims in the healthcare field. Outreach for this project was made possible through outreach consultants including the Muslim Wellness Foundation, Muslim Life Planning Institute, Masjid Muhammad, The Nation’s Mosque, and The Mosque Cares, as well as outreach partners including, American Muslim Health Professionals, Association of Muslim Chaplains, British Islamic Medical Association, CAIR-GA, CAIR-SFBA, ICNA Relief, Imamia Medics International, Inner-city Muslim Action Network, Islam in Spanish, Islamic Medical Association of North America (IMANA), Najah Bazzy, and Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS).

Our statistical analyses included summaries of various demographic factors as well as several multivariate logistic regression models developed using Stata 15.0 (StataCorp., 2015). We used relative risk ratios to define the relationship between numerous dependent and independent variables and controlled for race, gender, and age. The explanatory and outcome variables for these models were developed as follows.

Responses to the PHQ-4 were totaled into a score for each respondent, with which thresholds for “mild,” “moderate,” or “severe” psychological distress were applied. Sub-constructs for anxiety and depression are also included in the PHQ-4 scale, with which thresholds for screening positively for depression or anxiety were applied (see Appendix 1 for the full PHQ-4 scale). Given the particular goals of this study, as well as the unprecedented circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic, full pre-validated psychometric scales or behavioral models were not used to measure discrimination or coping method utilization in this survey. Instead, consultations with experts in the fields of medicine and social science (acknowledged as the “Advisory Team” for this report) were referenced to construct novel self-report items that explored behavioral, cognitive, religious, and non-religious coping strategies we believed were particularly relevant to this population and circumstance.

Experiences of discrimination were measured using single self-report items assessing the frequency of various types of discrimination both within and outside of the workplace “in the past year.” Coping method utilization was measured using a series of self-report items assessing the frequency of partaking in various behavioral and cognitive coping strategies (see “Coping Strategies” for a comprehensive list) to “help cope with the COVID-19 pandemic.” To include coping method utilization as an outcome variable in our multivariate logistic regression analyses, the research team categorized the coping strategies as “healthy” or “unhealthy” and assigned a score to each participant based on the frequency with which they reported utilizing each type of strategy. Reporting the use of a strategy “occasionally” or “regularly” was taken as a “yes,” while reporting “never” or “rarely” was taken as a “no” in our analyses. This distinction between “healthy” and “unhealthy” is intended to distinguish between strategies that are commonly linked with addictions or poorer mental health outcomes when used in excess such as “drugs and/or alcohol” and “eating comfort food” (Chiappini et al., 2020; Leger et al., 2014; Pool et al., 2015). It is important to clarify that these coping strategies are not inherently negative or positive; rather, they depend on a number of contextual factors. For example, online shopping can be seen as neutral if addiction or avoidance are not involved, and excessive exercise can be seen as negative or dangerous in some eating disorder contexts (Somer & Ruvio, 2013; Meyer et al., 2011). The analyses discussed in this report, therefore, must be understood as an exploration of coping strategies and mental health outcomes, not definitive conclusions about their impact or effectiveness.

Co-publishing organizations:

Institute for Social Policy and Understanding (ISPU)

ISPU provides objective research and education about American Muslims to support well-informed dialogue and decision-making. Our research aims to educate the general public and enable community change agents, the media, and policymakers to make evidence-based decisions.

Stanford Muslim Mental Health & Islamic Psychology Lab

The Stanford Muslim Mental Health & Islamic Psychology Lab serves as an academic home for the study of mental health in the context of the Islamic faith and Muslim populations. The Lab aims to provide intellectual resources to clinicians, researchers, trainees, educators, community, and religious leaders working with or studying Muslims.

.

Description of the Sample

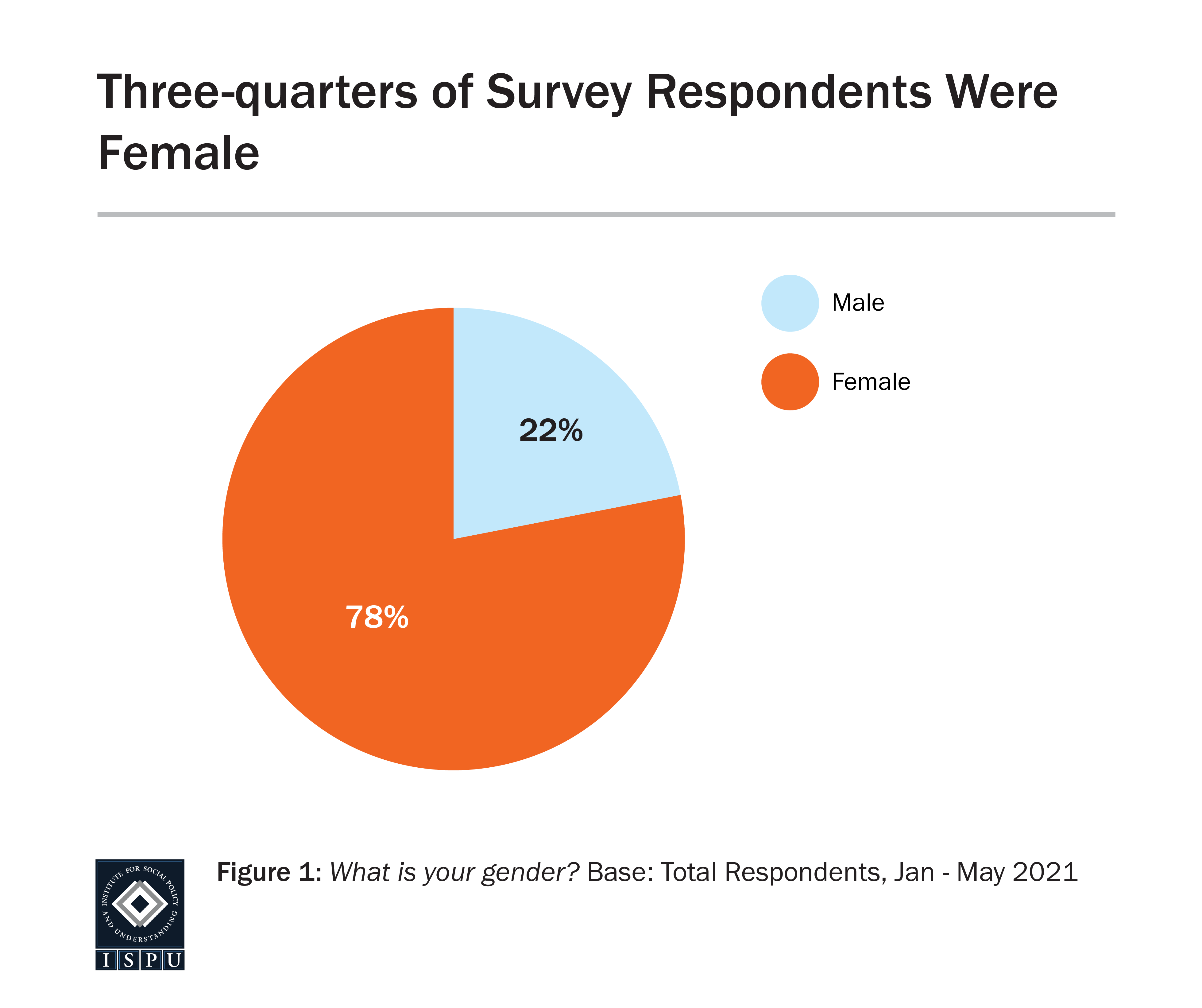

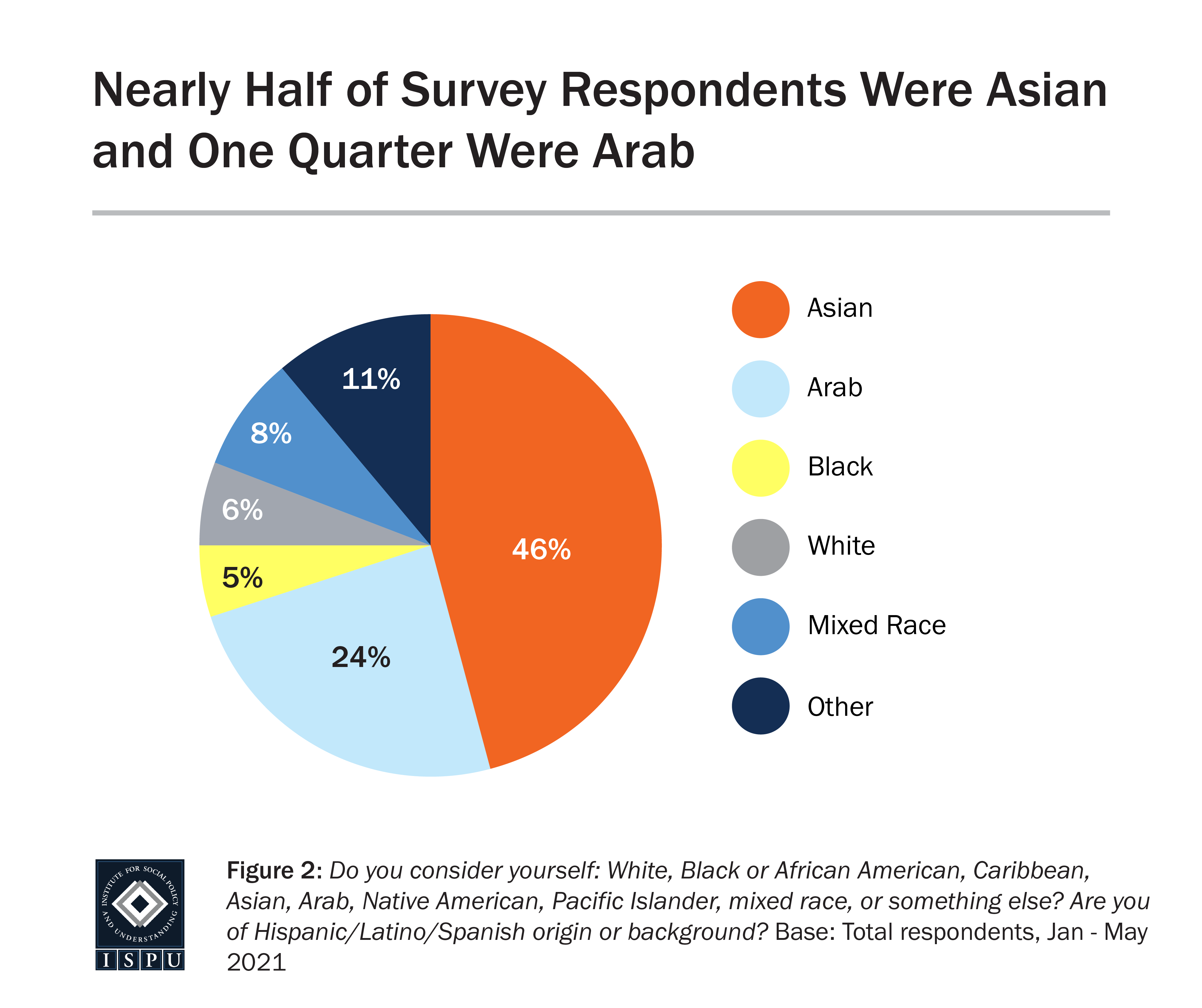

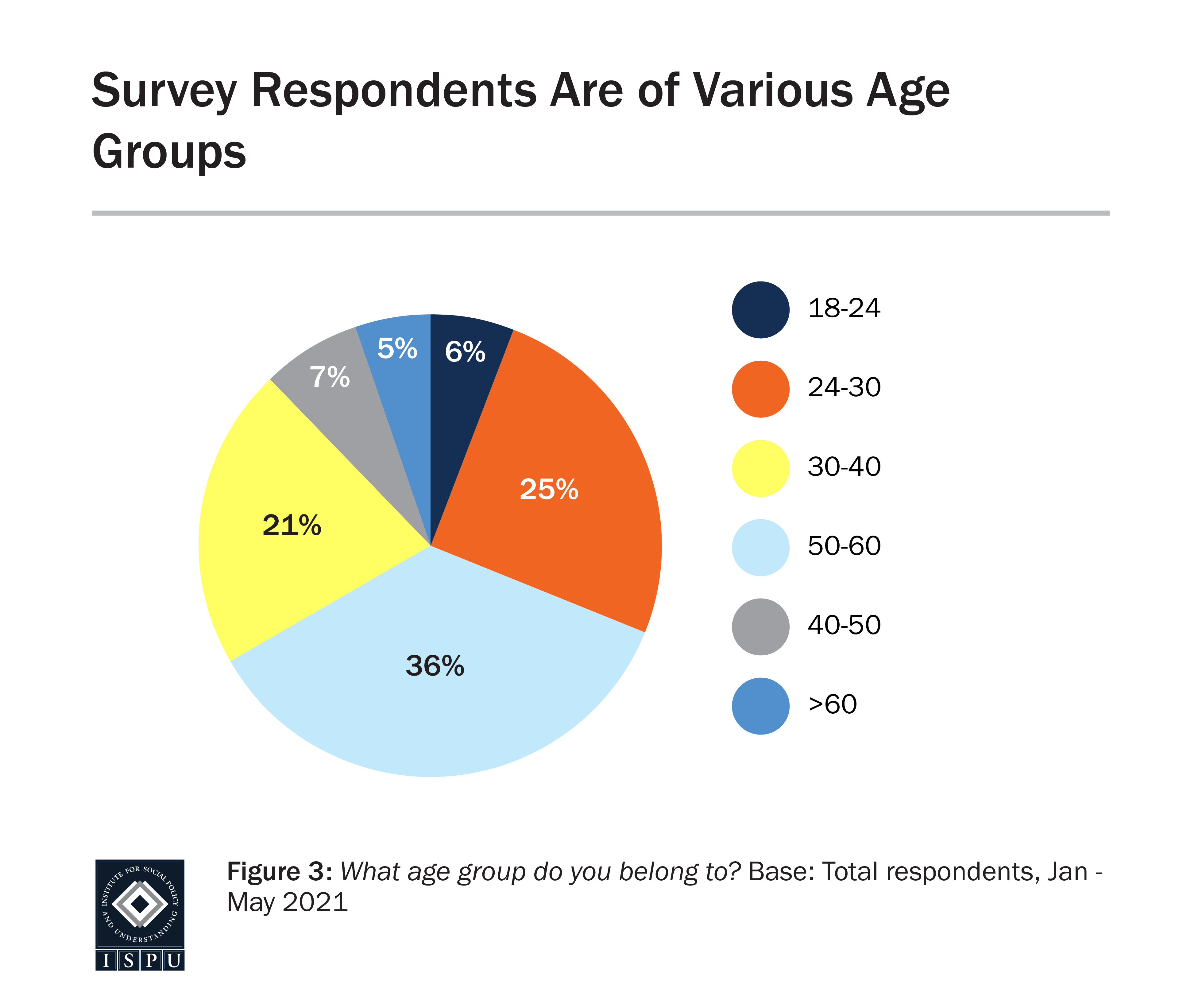

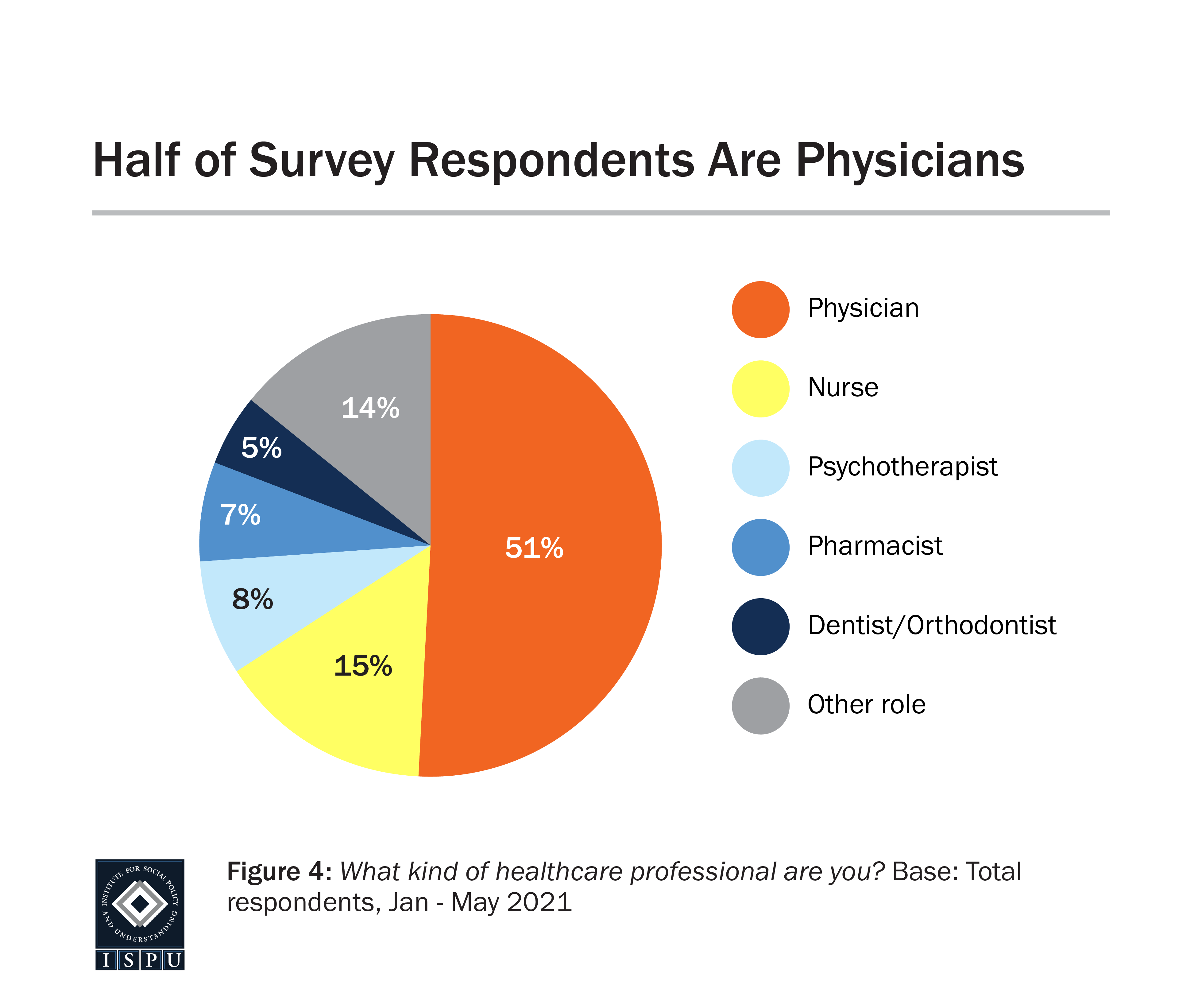

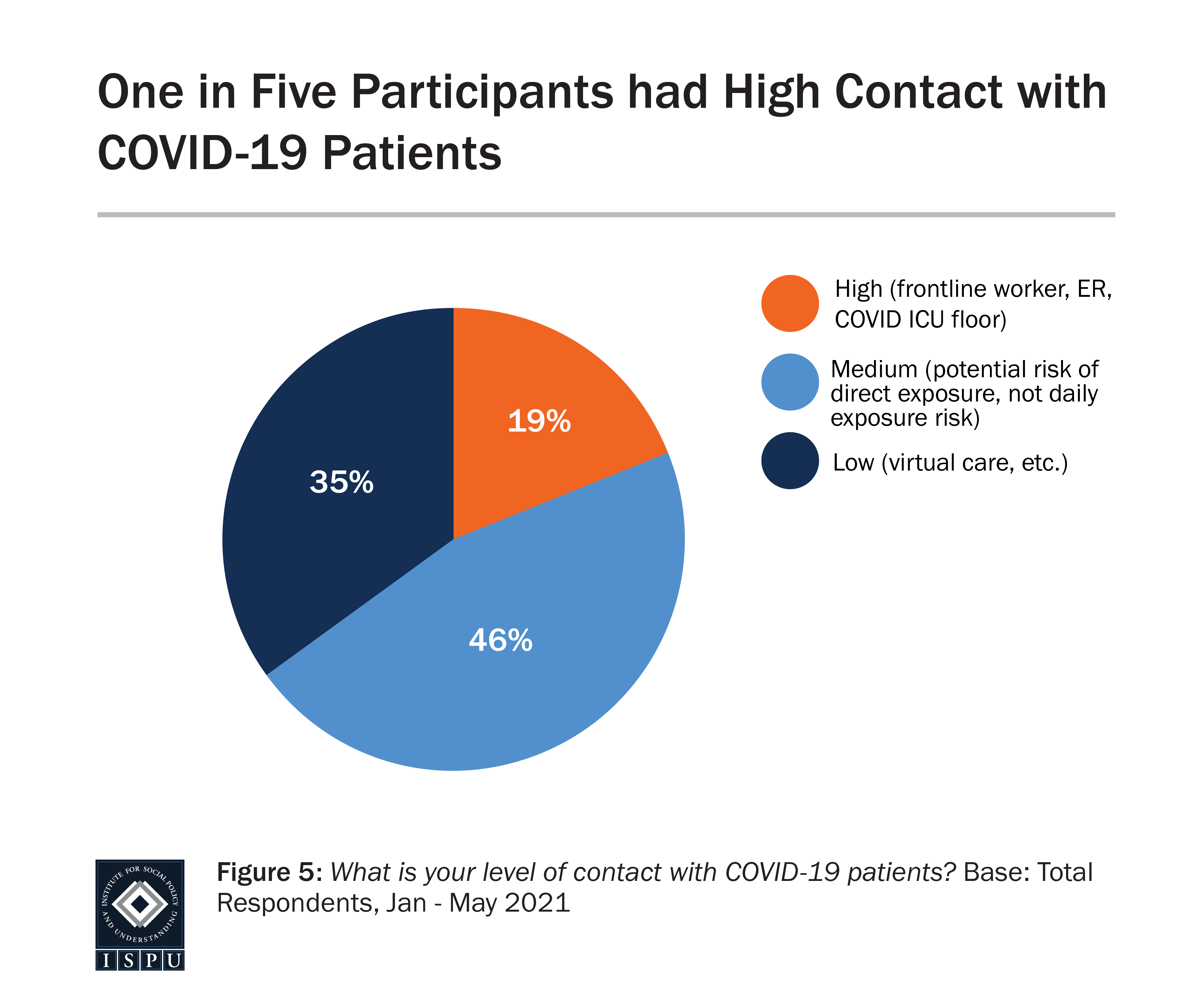

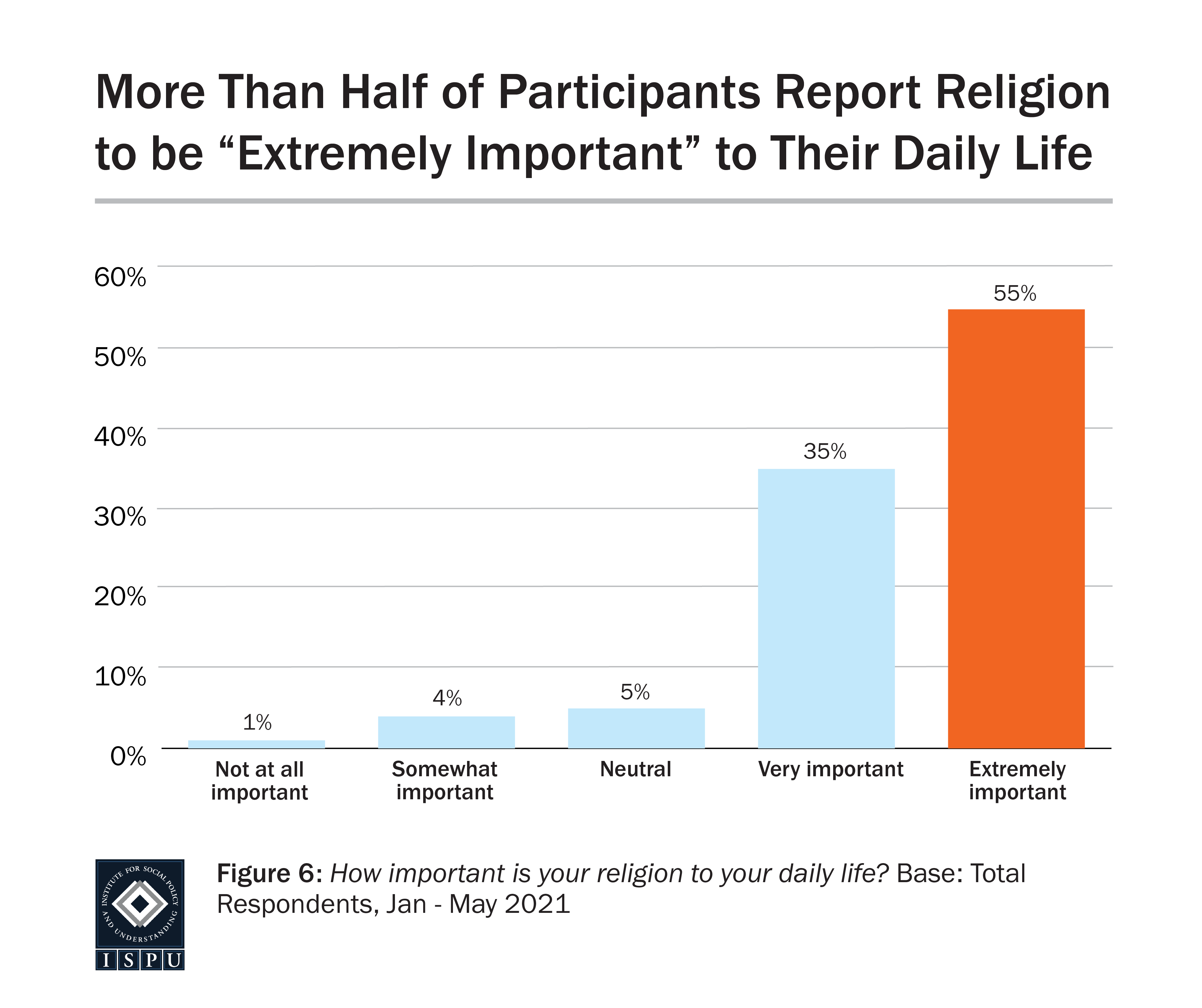

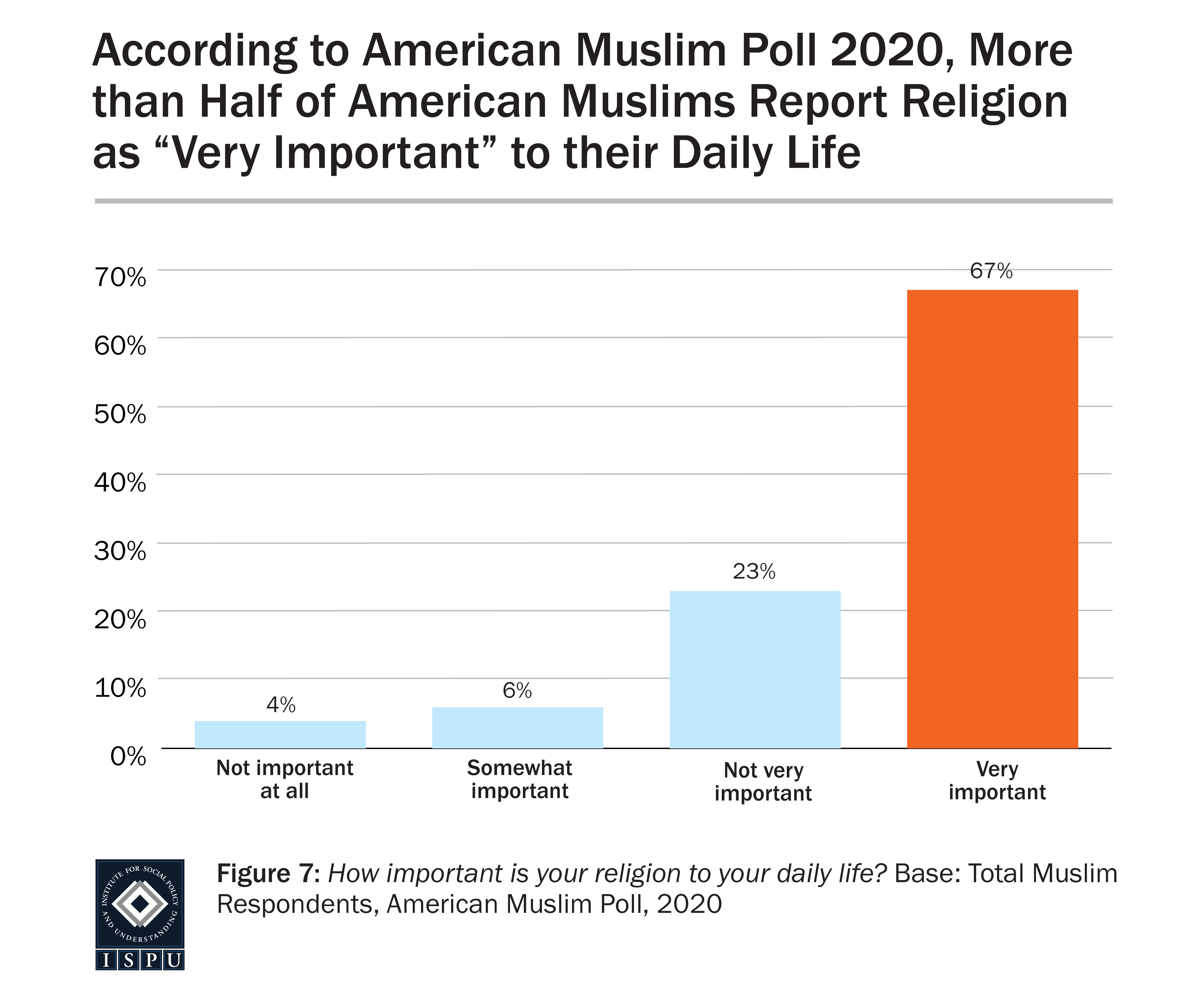

Overall, the sample of 692 was mostly female (78%) and largely Asian (46%) and Arab (24%). Thirty-six percent of the sample were between the ages of 30–40, and 28% were between the ages of 40–60. More than half (51%) of the sample practiced as physicians (attending or resident), about 15% practiced as nurses (RNs or NPs), and the sample also included psychotherapists (8%), pharmacists (7%), dentists/orthodontists (5%), and numerous other healthcare professional roles (chaplains, technicians, administration, and more). The sample reported a level of religiosity that is consistent with existing data on the wider American Muslim population collected in ISPU’s American Muslim Poll 2020. Fifty-five percent of our sample self-reported that religion is “extremely important” to their daily lives. During the recruitment process, significant challenges were faced in achieving a racially representative sample of American Muslim HCWs. Despite efforts to ameliorate this, our sample likely underrepresents the Black and African American Muslim population in the healthcare field. Despite marketing and partnerships with Black and African American platforms and influencers, this remains a noteworthy limitation to our study. As a result, extensive analyses across racial groups were very limited.

Impact of COVID on Mental Health and Distress

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in spring of 2020, the healthcare system worldwide was overwhelmed, causing frontline HCWs and all other healthcare workers to report increased levels of distress and anxiety (Lai et al., 2020). Healthcare workers not only faced stressors related to their work environment, they also faced increasing social isolation and disconnection, which can result in significantly worse mental health outcomes (Gomez-Duran, 2020). Work-related stressors for HCWs on the frontlines included lack of personal protective equipment (PPE), lack of organizational transparency, and loss of income (Physician Foundation Survey, 2020). In the United States, in 2021, there has been increased burnout throughout the physician population, with 61% of physicians reporting they often felt feelings of burnout compared to only 40% in 2018 (Physician Foundation Survey, 2021). Alarmingly, more than half of physicians know another physician who considered or attempted suicide (Physician Foundation Survey, 2021).

Significant stressors outside of the work environment that HCWs faced included the concern of infecting others outside of the hospital, taking care of elderly relatives who were at the highest risk of mortality from COVID-19, and taking care of children at home (Norful et al, 2021). This is especially significant for American Muslim HCWs who find their belonging and citizenship in the United States through their family, community, and work environment (Laird et al., 2013). However, the impact of these stressors on American Muslim HCWs’ mental health and ability to lean on such supports as their family, community, and work environment has not been thoroughly investigated. Research has shown that among Muslim HCWs outside of the U.S. (in Yemen and Saudi Arabia), these stressors caused increased fear, distress, and risk of developing anxiety and depression, irrespective of gender, sociodemographic status, or sector of work (Hafizi et al., 2014). Our study sought to gain similar insight into how HCWs in the United States were being impacted by pandemic-related stressors, given their exposure to compounded stress from discrimination and marginalization (Padela et al., 2016).

All research findings above point to a particular set of risk factors that Muslim HCWs potentially face. Our study hypothesized that a sample of American Muslim HCWs would report significant distress as a direct result of pandemic-related stress.

As anticipated, more than 80% of our study’s sample reported that they felt “more stressed” or “much more stressed” as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Stress in this particular case was measured using a single self-report question: “How has your level of stress been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, if at all?” and the definition of stress was left open to subjective self-report by the participants. The following figure summarizes the responses and shows that four in five participants reported that their stress increased.

Additionally, about 30% of our sample screened positively for severe or moderate psychological distress according to the PHQ-4, and nearly 60% of the sample reported feeling angry on a regular basis. Our survey also explored isolation through a single self-report item: “Please indicate the degree to which the pandemic has made you feel isolated.” Frequency was self-defined in this case, with options including “never,” “rarely,” “occasionally,” or “regularly.” Concerningly, almost 80% of our sample reported feeling isolated “occasionally” or “regularly.” Given the important role of factors such as family, community, and work environment to the population of interest to this study, this is particularly worrisome (Laird et al., 2013).

Coping Strategies

There has been little research conducted on American Muslim HCWs regarding their responses to stress, particularly the types of stress that were present during COVID-19. In particular, what coping strategies are commonly utilized within that population, and how impactful or effective were they on mental health outcomes. A coping strategy can be defined as a behavior a person partakes in or a belief a person relies on when dealing with stress, whether consciously or unconsciously, as an attempt to relieve their negative emotions. One study of the general Muslim population in the United Arab Emirates explored various religious and non-religious coping strategies utilized during the pandemic and found that religious coping alleviated depressive symptoms (Thomas & Barbato, 2020). A study from Indonesia explored how Muslim nurses in the Intensive Care Unit (prior to the pandemic) coped with proximity to death and dying and found that engaging with spirituality was one of four primary methods for avoiding burnout (Betriana & Kongsuwan, 2019). Another study of Muslims abroad looked specifically at HCWs in Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Nigeria, and investigated anxiety and stress related to the COVID-19 pandemic as well as their utilization of various coping mechanisms. It found that nurses, physicians, and other healthcare workers were able to alleviate stress through prayers, exercise, and other self-defined “relaxation activities” involved in religious practice (Rose et al., 2021). Unfortunately, comparable literature regarding the stress responses of Muslims living in countries where they are a minority (in the U.S. or otherwise) appears to be very limited, despite the potentially significant impact of discrimination on those populations.

Our survey sought to gain similar insight into American Muslim HCWs working in the U.S. and investigated a number of religious and non-religious behavioral and cognitive coping strategies by asking our respondents how often they found themselves utilizing them. Given the particular goals of this study as well as the unprecedented circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic, full pre-validated psychometric scales or behavioral models were not used to measure coping method utilization in this survey. Instead, consultations with experts in the fields of medicine and social science (acknowledged as the “Advisory Team” for this report) were referenced to construct novel self-report items that explored behavioral, cognitive, religious, and non-religious coping strategies we believed were particularly relevant to this population and circumstance. The following figures represent all the coping strategies that were investigated in our study, encompassing both behavioral and cognitive mechanisms. Distinctions such as “religious,” “non-religious,” “healthy,” and “unhealthy” were not labeled for the participants but were identified and incorporated during the subsequent data analysis stage.

Behavioral Coping

The figures below illustrate how often our sample was utilizing various behavioral coping strategies, both religious and non-religious in nature. The research team categorized the coping strategies as “healthy” or “unhealthy” with the intention of distinguishing between strategies that are commonly linked with addictions when used in excess or poorer mental health outcomes such as “drugs and/or alcohol” and “eating comfort food” (Chiappini et al., 2020; Leger et al., 2014; Pool et al., 2015). It is important to clarify that these coping strategies are not inherently negative or positive; rather, they depend on a number of contextual factors. For example, online shopping can be seen as neutral if addiction or avoidance are not involved, and excessive exercise can be seen as negative or dangerous in some eating disorder contexts (Somer & Ruvio, 2013; Meyer et al., 2011). The analyses discussed in this report, therefore, must be understood as an exploration of coping strategies, not definitive conclusions about their impact or effectiveness.

The most commonly used strategy reported in our sample was calling friends and family, with 82% of respondents reporting doing so either occasionally or regularly. This demonstrates that our sample of American Muslim HCWs often leaned on their social support networks to help cope with pandemic-related stress. This is a hopeful finding given previous research, which suggests that having a strong social support network has a protective effect against physician burnout and stress, preventing physicians from experiencing compassion fatigue (Song et al., 2021).

In our sample, the other most commonly utilized non-religious coping strategies were eating comfort food (79%), shopping online (62%), exercising (57%), and sleeping more than usual (51%). Religious coping strategies were used much more commonly than non-religious strategies as a whole, but extra du’aa (prayer of supplication or invocation) was particularly common (78%).

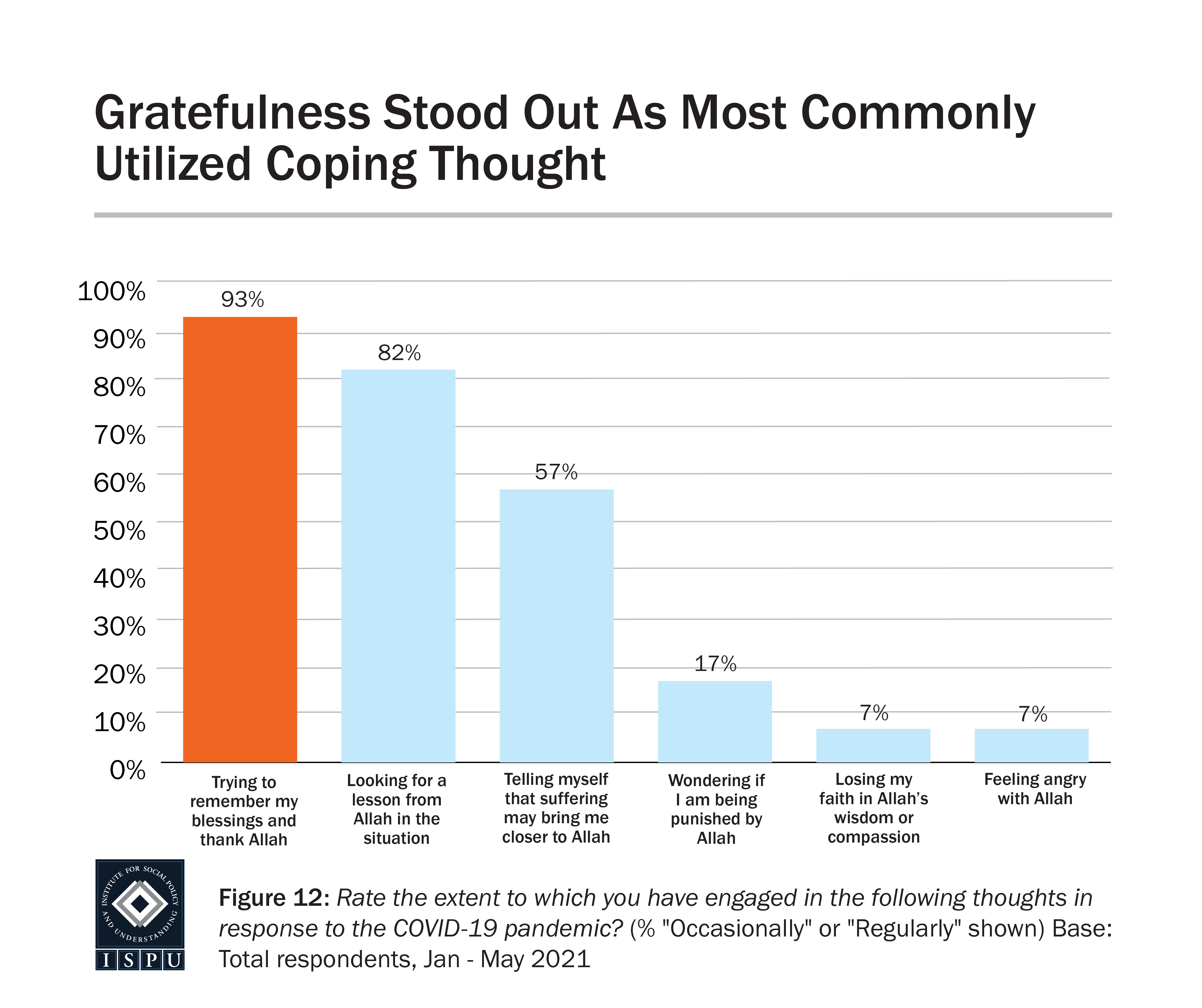

Cognitive Coping

In addition to discussing behavioral coping strategies, this study aimed to explore how American Muslim HCWs were perceiving and interpreting the stress of the pandemic through an Islamic religious lens. This was achieved by asking participants how often they found themselves engaging with thoughts related to both “healthy” and “unhealthy” religious perceptions “in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.” Healthy thoughts (e.g. “Trying to remember my blessings and thank Allah,” “Looking for a lesson from Allah in the situation,” or “Telling myself that suffering may bring me closer to Allah”) were consistently used more often than unhealthy ones (e.g. “Wondering if I am being Punished by Allah,” “Losing my faith in Allah’s wisdom or compassion,” or “Feeling angry with Allah”) with an average percentage of 77% and 10% respectively indicating that they engaged in those thoughts “occasionally” or “regularly” in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Some Coping Strategies Linked with Increased Risk of Distress

Some coping strategies are thought to be maladaptive, which have been linked to high psychological distress and lower overall mental health (e.g. self-blame, denial, disengagement, venting, and substance abuse); this is in contrast with positive, or adaptive, coping strategies that can successfully relieve negative emotion and promote well-being (Mong & Noguchi, 2021). Some potentially maladaptive coping strategies were observed in our sample that were significantly associated with poorer mental health outcomes, such as eating comfort food (79%), shopping online (62%), or sleeping more than usual (51%). According to our multiple logistic regression analyses, all of these strategies were linked to more than two times increased risk of moderate to severe psychological distress as measured by the PHQ-4. With regard to substance use, only 4% of our sample reported using tobacco products and 3% of our sample reported using drugs and/or alcohol as a coping strategy; however, this is not necessarily an accurate assessment given that self-reporting substance use is heavily underreported in the general population, let alone a faith community where their use is religiously prohibited (Rockett et al., 2006).

This survey’s investigation of how American Muslim HCWs were perceiving and interpreting the stresses of the pandemic through an Islamic religious lens revealed a number of noteworthy findings. Firstly, HCWs who reported wondering if they were being punished by Allah occasionally or regularly were at significantly higher risk of moderate to severe psychological distress according to the PHQ-4. Additionally, according to the PHQ-4 anxiety and depression sub-constructs, HCWs who engaged with this thought occasionally or regularly were at significantly increased risk for screening positively for both anxiety and depression. Those who reported thoughts of feeling angry with Allah occasionally or regularly were also more likely to screen positively for depression compared with HCWs who did not feel this way, after controlling for other coping strategies, race, gender, and age. These findings are supported by existing research looking at chronic illness in cancer patients, which showed that negative religious coping strategies were associated with poorer overall well-being (Hebert et al., 2009).

It is important to state that these associations do not imply a causal relationship between religious cognitions and mental health. That is, it cannot be concluded that “Feeling angry with Allah” directly resulted in increased distress; rather, those who reported “Feeling angry with Allah” were more likely to have poorer mental health outcomes in our sample. The sources or direct causes of that distress are inherently multifactorial and would require further in-depth research to particularly identify. However, the discovery of these associations warrants further investigation into the impact of religious cognitions on coping with stress and maintaining mental well-being.

Interestingly, some coping strategies that were deemed as “healthy” were also associated with increased risk of distress, particularly journaling (up to 1.96 times the risk) and extra du’aa/supplication (more than two times the risk) according to our multivariate regression analyses. This does not necessarily mean that utilizing journaling or extra du’aa caused decreased mental health or increased distress. Rather, these paradoxical associations may indicate that those American Muslim HCWs who were experiencing moderate to severe psychological distress were the most likely to use those strategies. However, to better understand these associations, further research should be conducted to understand the exact circumstances, intensities, and frequencies with which American Muslim HCWs partake in these coping strategies.

See Appendix 2 for a detailed tabulated summary of these findings.

Feeling Angry with Allah was Strongly Linked to Feeling a General Sense of Anger on a Regular Basis and Risk for Depression

Interestingly, our multivariate regression analysis also revealed that Muslim healthcare workers who reported thoughts of feeling angry with Allah were more than eight times more likely to also report feeling a general sense of anger on a regular basis. See Appendix 3 for a detailed tabulated summary of this finding. This reveals an opportunity for future research to investigate a potential link between anger inspired by environmental factors such as the pandemic and anger directed toward metaphysical/spiritual beliefs; our study alone cannot infer a link between these factors. However, given the importance of religious beliefs and practice reported by our study’s sample, and the role of religious coping strategies highlighted in both our analyses and those of previous literature, this link has significant potential implications. Further research must be conducted on how anger caused by environmental factors influences metaphysical/spiritual beliefs and perceptions, and vice versa, to understand how that can impact a religious individual’s ability to utilize their faith as a positive coping tool during times of distress.

Remembering Blessings and Thanking Allah was Widely Protective

In our study, those who reported trying to remember their blessings and thank Allah were at a significantly reduced risk for psychological distress, after controlling for other coping strategies, race, gender, and age. This was the most protective religious coping strategy revealed by our study.

This finding can be connected to one of the most well-studied cognitive coping strategies in the field of psychology: gratefulness. The emerging field of positive psychology provides deep insight into the impact of such interventions as: writing down three good things that happened every day and making a habit of expressing thanks to people in one’s life. These interventions result in marked increases in subjective well-being (Selgiman et al., 2005). It is theorized that shifting one’s attention to positive experiences and focusing on the positive impact of events can train the brain to be more optimistic and hopeful, both of which are protective against disorders like depression and anxiety (Adair et al., 2020).

Additionally, gratefulness is a crucial concept in the religion of Islam. The concept of “Al-Shukr” is emphasized throughout the Holy Qur’an and the sayings of the Prophet Muhammad (ﷺ). In both traditional and contemporary understandings, it plays a vital role in spiritual and psychological development for Muslims. For more detailed exploration of this topic, see Yaqeen Institute for Islamic Research’s publication titled “Islamic Spirituality and Mental Well-Being (Abdul-Rahman, Z.; 2017).

HCWs from our study reported utilizing gratefulness at a high rate (93%), indicating that this was a commonly held value. The protective impact of this strategy, on top of expansive existing literature, points to another major strength among American Muslim HCWs. Alongside our finding showing the prevalence of calling friends and family (used by more than 80% of participants), our study reveals a strong tendency for our participants to utilize healthy coping strategies that are well-supported by existing evidence derived from the general public (Seligman et al., 2005). These strategies can be capitalized on and encouraged among American Muslim HCWs to further protect against the stresses of their role, particularly amidst a pandemic.

Seeing a Mental Health Professional During the Pandemic was Widely Protective

Some existing literature has found that Muslims in North America utilize professional mental health services at a lower rate compared to other groups, with possible reasons including internalized self-stigma and public stigma (Zia et al., 2021). However, a large majority of our sample reported seeing a mental health professional both before (67%) and during (83%) the pandemic (specifically to help with the impact of COVID-19). Interestingly, other data collected by ISPU, namely the 2021 “Community in the Time of Corona” report, supports this finding, with Muslims who report experiencing negative emotions so much that it interferes with their daily lives were as likely as the general public who had the same level of distress to seek out a mental health professional. This suggests that further research into mental healthcare utilization among American Muslim HCWs and the wider American Muslim community is warranted and that new trends may be emerging.

The increase in mental healthcare utilization from before the pandemic to during the pandemic is potentially emblematic of the severity of COVID-19’s impact on the mental health of our sample. Other potential explanatory factors include the increased ease of access provided by telehealth options during the pandemic, but further research is needed to delve further into this trend.

Importantly, seeing a mental health professional during the pandemic was found to reduce risk for feeling angry, screening positively for depression, anxiety, and mild and moderate psychological distress according to our multivariate logistic regression analysis. See Appendix 4 for a detailed tabulated summary of this finding. This finding is significant, particularly given previous evidence that Muslims underutilize mental healthcare. It is hopeful that our sample was able to demonstrate the importance of utilizing professional help to cope with the impact of COVID-19; this may provide evidence for other populations within the Muslim community that seeking mental healthcare is beneficial. Additionally, it remains important to continue spreading awareness about the necessity of seeking professional mental healthcare because despite a possible trend of increased utilization among American Muslim HCWs, there remains a disparity between the proportion of that population that utilize services and the proportion of the overall American Muslim population who are in need of services. To further protect the psychological well-being of both the general U.S. Muslim population and the HCW population in particular, more awareness programming and field research must be conducted to help understand and treat the manifold challenges being faced.

Discrimination

Discrimination is a source of compounded distress for marginalized groups such as Muslims in the United States. Not only does it increase distress, but it has also been shown that American Muslim HCWs who perceived discrimination in the workplace reported lower job satisfaction and higher turnover (Nunez-Smith et al., 2009). In the healthcare field specifically, previous research has shown that American Muslim HCWs who reported religion to be an important aspect of their life had greater odds of perceiving religious discrimination at their current workplace and compromised the majority of those who had left their jobs due to perceived religious discrimination (Padela et al., 2016). In the same study, nearly half of the respondents perceived greater scrutiny at work due to being Muslim. Fifty percent struggled to find time to pray at work. Another survey conducted by the British Islamic Medical Association surveyed more than 100 British Muslims healthcare workers, of which 81% reported Islamophobia or racism and 57% felt that Islamophobia was holding them back from progressing in their careers (Day, 2020). The present study investigated the degree to which various forms of discrimination were perceived to be impacting American Muslim HCWs and analyzed how that impacted their psychological distress and coping strategies.

Frequency of Discrimination

In this study, Muslim healthcare worker participants were asked to report how often they experienced discrimination based on their religion outside of the workplace and within the workplace. Additionally, they were asked to report how often they experienced racial and gender discrimination within the workplace over the last year. Forty-seven percent of the overall sample reported experiencing at least one form of discrimination. Thirty percent of the sample reported experiencing religious discrimination occasionally or regularly outside of the workplace, and 19% reported experiencing Islamophobia within the workplace. In regard to racial discrimination within the workplace, 22% of those surveyed reported occasional or regular incidents. Lastly, 25% reported experiencing gender discrimination within the workplace. These findings are corroborated by the study conducted by Padela and colleagues, where it was found that the prevalence of perceived religious discrimination was lower than racial/ethnic discrimination in other studies. Interestingly, however, Padela and colleagues found that those for whom religion was an important aspect of their life had greater odds of perceiving religious discrimination at their workplace. Our study was unable to add support for this finding, given the nearly negligible proportion of our sample that reported low importance of religion (although this is consistent with existing ISPU data). However, further research into the link between perceived importance of religion and perceived experiences of religious discrimination is warranted.

Discrimination Associated with Higher Risk of Psychological Distress, Including Depression and Anxiety

While a majority of participants did not report experiencing occasional or regular discrimination, this study aimed to investigate the mental health outcomes of those who did report regular or occasional discrimination. Particularly, how was discrimination related to mental health outcomes for our sample? Additionally, which types of discrimination, or intersections therein, were most correlated with distress? Through multivariate logistic regression models, several noteworthy results were extracted from the data.

It was revealed that those HCWs who reported experiencing occasional or regular religious discrimination outside of the workplace in addition to racial discrimination within the workplace, compared to those who experienced no discrimination, had five times higher risk of mild psychological distress, and 6.6 times higher risk of moderate or severe psychological distress, controlling for race, gender, and age. HCWs experiencing occasional or regular discrimination of mixed forms (racial, gender, or religious), compared to those who experienced no discrimination, had five times higher risk of mild distress, and nine times higher risk of moderate or severe distress. See Appendix 5 for a detailed tabulated summary of these findings.

It has been shown in the general U.S. workforce that harassment and discrimination is a prevalent issue associated with poor mental health outcomes (Rospenda et al., 2008). A study examining suicide ideation among physicians and trainees found that workplace harassment, including degrading comments and offensive language or acts, to be among the primary factors associated with suicide ideation (Eneroth et al., 2014). Specifically looking at Islamophobia, a systematic literature review was run by Samari and colleagues using keywords related to discrimination, Muslim identifiers (including Muslim-majority nationalities), and health outcomes. It found significant associations between Islamophobia and poor mental health, suboptimal health behaviors, and unfavorable health care-seeking behaviors (Samari et al., 2018). Our findings, unsurprisingly, provide further evidence that discrimination in the workplace is strongly associated with negative mental health outcomes and that this holds true for our population of American Muslim HCWs.

This information is particularly concerning given that, in the absence of strong protective factors, these outcomes could be even further exacerbated. This sample, as discussed previously, utilized numerous widely protective coping strategies at a high rate, leading to the question of how HCWs who do not partake in those protective strategies may be even further impacted by experiences of discrimination. Additionally, it is not well known how likely Muslims are to actually report instances of discrimination, particularly Islamophobia. Further research is needed to understand what experiences may have gone unreported in our data.

Religious Discrimination in the Workplace Associated with Increased Healthy Coping Strategies, Particularly Those of a Religious Nature

Beyond the psychological impact of discrimination on American Muslim HCWs, another goal of this study was to analyze how they were coping with the impact of discrimination on top of the stress of COVID-19. It was found that those who reported experiencing religious discrimination within the workplace were significantly more likely to utilize “healthy” coping strategies, particularly religious healthy coping strategies. Additionally, they were less likely to utilize “unhealthy” coping strategies. See Appendix 6 for a detailed tabulated summary of these findings.

Previous literature can help make sense of this finding. It may be expected that those who face religious discrimination, and therefore greater psychological distress, would have a more difficult time engaging in healthy coping strategies. However, previous literature has suggested that those who perceive Islamophobia tend to also view religion as a more important part of their life (Padela et al., 2016). Therefore, it is possible that those in our sample who reported religious discrimination also felt a strong connection to their faith as part of their life and identity, which may be related to their higher utilization of healthy religious coping strategies. However, further research into the link between self-reported importance of religion and perceptions of religious discrimination must be conducted to gain insight into the impact of religious discrimination on effective coping.

Racial Discrimination in the Workplace Associated with Less Healthy Coping and More Unhealthy Coping

In contrast to the above finding, those healthcare workers who reported racial discrimination in the workplace were found to be less likely to utilize healthy coping strategies and more likely to utilize unhealthy religious coping strategies. This finding raises a number of important questions. See Appendix 6 for a detailed tabulated summary of these findings. Firstly, why is it that experiences of racial discrimination and religious discrimination are associated with such different patterns of coping? Secondly, what are the factors that impact an individual’s perception of discrimination as either targeting their race, religion, or both? Thirdly, what aspects of those experiences lead to the utilization of different healthy and unhealthy coping strategies? Lastly, what can be done to promote the utilization of healthier coping strategies when an individual is experiencing racial discrimination? More in-depth research into the multifaceted phenomena of discrimination among Muslims and Muslim HCWs, including qualitative research examining the nuances of identity, perception, and stress response, is vital to exploring these questions. Presently, our study reveals that racial and religious discrimination are associated with divergent patterns of coping, but little else can be concluded.

Recommendations

This report presents a body of evidence to suggest that American Muslim HCWs may be at increased risk for a number of negative mental health outcomes resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as discrimination. However, we also present evidence to suggest that there are numerous tools and strategies being utilized in the population that may be promoted to ameliorate those adverse outcomes. Existing research has found significant protective effects of system-wide mental health interventions in the general HCW population, including such programs as peer-to-peer support and designated professional mental health care (Albott, 2020). Given the particular risks faced by American Muslim HCWs, our study provides insight into how such programs can be tailored to the particular needs of this marginalized population.

Healthcare Systems:

-

- Firstly, healthcare systems that employ American Muslim HCWs should provide easily accessible mental health support to their healthcare professionals. Primarily, systems must provide easy access to professional mental healthcare, given our study’s findings that utilizing professional mental health services was associated with better mental health outcomes and healthier coping strategy utilization.

- Secondly, our study highlighted several widely protective coping strategies being utilized in our sample, many of which are compatible with existing empirical literature and Islamic cultural practices. Healthcare systems should support these strategies in particular by allowing space and time for the practice of healthy religious coping strategies like extra prayer and reading Qur’an, as well as non-religious coping strategies like calling friends and family. Each of these strategies was found to decrease the risk of adverse mental health outcomes, possibly by providing connections to individual strength and interpersonal support in our sample.

- Lastly, to combat the compounded effects of discrimination on the mental health and coping abilities of American Muslim HCWs, healthcare systems should incorporate Islamophobia awareness and prevention into existing diversity and inclusion programming. This training must additionally encourage leadership to intervene in cases of active prejudice and marginalization amongst their workforce and provide all necessary support and guidance to upkeep the mental health of those who have been targeted. To this end, data collection and documentation about the prominence of Islamophobia and other forms of discrimination in healthcare settings must be facilitated to provide the necessary evidence for interventions. This information should be made transparent and available to assist the work of all who wish to support the mental health needs of American Muslim HCWs, both during this COVID-19 pandemic and beyond.

Individuals:

-

- Firstly, our study’s investigation of negative religious thoughts highlighted that some methods for cognitively processing adversity are maladaptive. Such thoughts as, “Wondering if I am being punished by Allah,” and “Losing my faith in the wisdom or compassion of Allah,” and “Being angry with Allah” were all associated with negative mental health outcomes. Awareness of these maladaptive cognitions is important for American Muslim HCWs as they continue to face challenges in their workplaces and beyond. Reliance on aforementioned healthy outlets such as friends and family, as well as other religious strategies, may be a promising avenue for mitigating these negative thoughts.

- Secondly, gratefulness, particularly remembering blessings and thanking Allah, stood out as not only one of the most widely utilized cognitive coping strategies in our study but also as one of the most protective against adverse mental health outcomes. Individual American Muslim HCWs should note the importance of this concept in both the religion of Islam and the pursuit of mental well-being (Abdul-Rahman Z., 2017). Highlighting this thought during self-care activities, which may include other coping mechanisms outlined in our study, such as calling friends and family and extra du’aa, may be a powerful tool for supporting mental resilience in the face of stress.

- Lastly, our study emphasized the protective power of seeing a mental health professional. Utilizing professional mental health services was associated with better mental health outcomes and healthier coping strategy utilization, and existing research has found it to be an effective support for the general HCW population amidst the pandemic. Individuals who have not sought professional mental healthcare to help cope with the COVID-19 pandemic should consider doing so, in addition to incorporating mental health services into their future strategies for self-care as new stressors continue to emerge.

Research Team and Advisors

Research Team

Communications Team

Katherine Coplen

Director of Communications, Institute for Social Policy and Understanding

Rebecka Green

Communications and Creative Media Specialist, Institute for Social Policy and Understanding