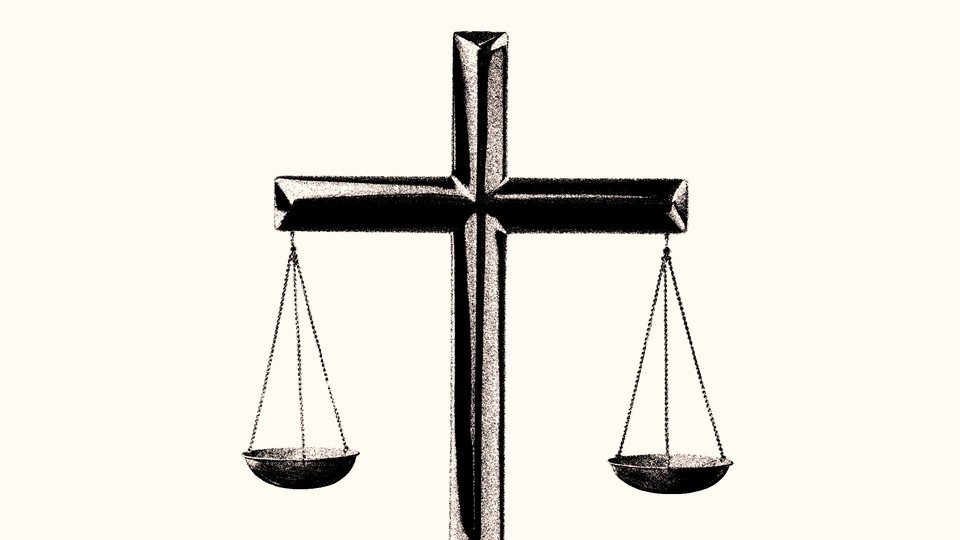

The Supreme Court Has Ushered In a New Era of Religion at School

For two centuries, America had kept questions of church and state at bay. The country is not ready for the ones to come.

Religious conservatives have been fighting for years to get prayer back into America’s schools, and this year, the Supreme Court gave them what they wanted. In Kennedy v. Bremerton, the six conservative justices affirmed a coach’s right to offer a prayer after a football game.

But what is really astonishing is that this decision will over time prove to be less monumental than the Court’s other big religion decision this term. In Maine’s Carson v. Makin, the Court ruled 6–3 that a state could not exclude private religious schools from receiving public funding only because of their religion. In prospect, it opens up a vast new world of publicly funded religious schools—using tax money, potentially—to teach kids that dinosaurs walked with humans, that girls primarily come into this world to grow up and bear children, or that only heterosexuals deserve rights. Maine quickly passed a law to keep public money away from avowedly anti-LGBTQ schools, but legislators will only be able to play anti-discrimination whack-a-mole for so long. Carson, not Kennedy, is the decision that could reshape the relationship of Church and school in America—even though prayer in school has long been the symbolic victory conservatives were intent on winning.

The reasons that prayer in school became the hallmark fight of this movement go back to the middle and late 20th century, when the Supreme Court decided a series of cases that conservatives thought “kicked God out of the schools.” In 1962, in Engel v. Vitale, the Supreme Court ruled that public schools could not require students to recite a state-written prayer. Politicians rushed to condemn the decision. Representative Frank Becker of New York called the decision “the most tragic in the history of the United States.” Ex-President Herbert Hoover joined ex-President Dwight Eisenhower in protesting the decision, declaring it the end of the country’s public-school system.

To Americans who cared a lot about religion, however, the decision seemed like a good one. Conservative evangelical Protestants looked askance at the bland wording of the prayer—it left out any specific mention of Jesus—and they did not approve of government-written prayers in the first place. From the fundamentalist citadel of the Moody Bible Institute, in Chicago, President William Culbertson wrote, “Christians who sense the necessity for safeguarding freedom of worship in the future are always indebted to the Court for protection in this important area.”

That all changed the next year, with the Court’s decision in School District of Abington Township, Pennsylvania v. Schempp. In Schempp, the Court ruled that some of the religious staples of American public schooling veered too far into controversial territory. It ruled against teachers leading students in prayer, and against students reading the Bible in class as part of a prayerful practice.

For America’s conservative Christians, even evangelicals who had supported the Engel decision, that was too much. Evangelical editors ranked the Schempp decision as the most devastating, world-changing event of 1963, more important to America and to Christianity even than the bombing of Birmingham’s 16th Street Baptist Church, with its murder of Christian children. Madalyn Murray O’Hair, the outspoken atheist who helped bring the Schempp cases to court, was attacked relentlessly, labeled by Life as “The Most Hated Woman in America.”

Ambitious politicians scrambled to pass a constitutional amendment to bring prayer back to public schools. New York’s Becker persuaded his colleagues to unite behind a single, simple change to the Constitution. The amendment explicitly stated that the Constitution never prohibited prayer or Bible reading in public schools or other government functions. The Republican Party added a plank to its party platform in favor of the amendment. By 1965, however, the amendment drive had lost steam.

Conservatives despaired. As one conservative Christian wrote in 1965, the end of school prayer meant the end of American Christianity itself. The Schempp decision, he warned, was only the start of “repression, restriction, harassment, and then outright persecution.” From the conservative evangelical Biola University, near Los Angeles, President Samuel Sutherland concluded that the decision and the failure of a constitutional amendment signaled America’s transformation into “an atheistic nation, no whit better than God-denying, God-defying Russia herself.”

By the early 1970s, the Supreme Court offered some guidelines for a shaky new détente about religion and public schools. In Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971), Chief Justice Warren Burger defined a three-prong standard: Any school law had to have a primarily secular purpose, it couldn’t promote or inhibit religion, and, most famously, it had to avoid “excessive government entanglement with religion.”

The “Lemon test” never satisfied conservatives who desperately hoped to entangle their government with their religion, but repeated efforts at a constitutional amendment went nowhere. In 1982, President Ronald Reagan reenergized efforts with his own version, but tensions between Reagan and conservative leaders such as Senator Jesse Helms of North Carolina ultimately doomed that effort as well. And that’s where things stood for the final decades of the 20th century and the start of the 21st, until now. In his majority Kennedy opinion, Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote that only “discrimination” against religion could explain the attempt to stop a coach from his “brief, quiet, personal religious observance.” He explicitly rejected the Lemon test, invoking instead the vision of public religion held by the Founding Fathers.

But in ways that would have shocked Becker and Reagan, the Court’s decision in favor of public-school prayer has become the junior partner in this year’s school-religion revolution. Yes, prayer has been allowed back into public schools, but, away from the bright lights of the football field, the Court has worked assiduously to make a much more profound change. More than simply allowing prayer back into public schools, the Carson decision will result in taxpayers being forced to pay for schools that strive to instill controversial religious ideas into students—a far greater offense to religious liberty than allowing prayer in school.

The Carson victory has been decades in the making. As Justice Clarence Thomas argued in a 2000 majority opinion in Mitchell v. Helms, excluding religious schools from government aid programs merely because they were religious represented rank “bigotry.” In 2002, in Zelman v. Simmons-Harris, Chief Justice William Rehnquist widened that opening, in a decision that allowed tax money to be used for tuition vouchers at religious schools. The goal, according to Rehnquist, was to provide “genuine choice among options public and private, secular and religious.” In 2020, Chief Justice John Roberts knocked a huge hole in the wall between religious schools and tax funding, opining in Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue that excluding religious schools from tax-funded programs represented an unjustifiable kind of “unequal treatment.” In his Carson v. Makin opinion, Roberts demolished the wall entirely. Excluding a religious school because it taught controversial religious ideas, Roberts wrote, was nothing less than rank “discrimination against religion.”

These justices and their conservative supporters might be sincere in their hope to combat “bigotry” and offer religious families real “choice” and equal treatment. They might honestly believe that they are restoring America to its original constitutional vision, guided by the wisdom of the Founding Fathers. But their decisions ignore the real history. They have taken America back into dangerous territory, in which taxpayers will be required to pay for religious ideas they consider abhorrent. Two centuries ago, Americans wisely chose to steer clear of those dilemmas.

The key at the time was Americans’ understanding of the word sectarian. Two hundred years ago, American public institutions—including public schools—included plenty of religious practice by 21st-century standards. But they avoided using public money to pay for schools that taught controversial religious ideas—what they called “sectarian” ideas. As the historian Steven K. Green has demonstrated, in the early 1800s, Americans worried—with good reason—about government intervention in intractable religious controversies.

It wasn’t a simple decision. At the time, American public opinion learned its lesson the hard way, through bitter, repeated school culture wars.

In the early 1800s, in the most famous example, Dartmouth College was racked with religious and political discord. One faction of faculty and students wanted to transform the institution into a purer sort of Christian school. An earnest student group successfully banned the long tradition of “treating” among students—in which students would get drunk to celebrate the announcement of their leading roles in commencement ceremonies.

The ban wasn’t popular. In 1809, many of the rest of the students rioted, firing guns at the headquarters of the student religious group, even blasting a cannon on campus. No one was hurt, but the disgruntled students made their point. They would not accept the leadership of one group of students who wanted to force their definition of Christianity on the whole campus.

The rioting students had the sympathy of the college president. His supporters accused the anti-alcohol students of trying to turn Dartmouth “into a sectarian school.” But the puritan faction had its faculty supporters as well. Those professors accused the rioters and their supporters—presumably including the college’s president—as “fighting versus God, trampling under foot his bleeding Son.”

The state of New Hampshire waded in, and the case eventually made its way to the U.S. Supreme Court. In 1819, the Court issued its landmark decision in Dartmouth v. Woodward. It chose not to choose at all, to build the beginnings of a wall between public funding and religious controversies. The Court refused to decide which side represented true Christianity, the one with drinking or the one without. It refused to decide which Christian leader was “fighting versus God.” Instead, the justices declared such controversies beyond the reach of government decision.

As with most culture-war issues, one Supreme Court decision did not settle things. For years in the early 1800s, Americans battled over the proper role of tax funding for religious schools. As Green wrote in The Bible, the School, and the Constitution, in New York City in 1822 the Bethel Baptist Church made its case for more tax funding for its tuition-free “charity schools.” At the time, the notion that religious schools would receive some portion of state money was not unusual. New York’s church schools, run by a host of denominations including both Protestants and Catholics, had long divvied up funding from the city to educate low-income youth.

It was a mess. Taxpayers unhappily funded a host of religious schools, paying for children to learn religious ideas they found objectionable. In 1825, New York’s Common Council decided—like the Supreme Court a few years earlier—that there was no good way for government to become entangled with controversial religious ideas, so it strengthened the wall between the public treasury and any school that promoted “private and sectarian interests.”

As New York’s leaders recognized at the time, the decision came down to choosing between an unpopular position and an impossible one. The city could cut off funding to any school that taught controversial, “sectarian” religious ideas, which would be unpopular. Or it could keep funding all religious schools, no matter how controversial their doctrines, but that would be impossible—it would force taxpayers to pay for every religious school, no matter what beliefs it taught.

The choice was clear. No tax money would go to any sectarian school. In the language of 1831, the Council declared, “If all sectarian schools be admitted to the receipt of a portion of a fund sacredly appropriated to the support of common schools, it will give rise to a religious and antireligious party, which will call into active exercise the passions and prejudices of men.”

Though things changed a great deal between the early 1800s and the late 1900s, that principle remained in place. Public schools and public funding would be walled off from any controversial religious ideas. The definition of a controversial religious idea was itself always controversial, and certainly many definitions were guided by widely shared Protestant prejudices, but when by 1963 common practices such as devotional Bible reading and teacher-led prayers had come to seem undeniably controversial, the Supreme Court ruled them out. It wasn’t any more popular in the 1960s than it had been in the 1820s, but it was the only possible solution.

In the name of fighting anti-religious “bigotry” and promoting school “choice,” today’s Supreme Court has ignored this hard-learned lesson. Instead, it has chosen to fan 21st-century “passions and prejudices.” It has chosen, in Kennedy, to see the very public prayers of a very public school figure as somehow a “private religious exercise.” And it has denounced as “discrimination” in Carson the idea that government might try to exclude religious schools only because they taught profoundly, disturbingly controversial ideas—only because they proudly discriminated against LGBTQ students, as well as Catholics, Muslims, Jews, Hindus, Buddhists, even most other Protestants, and of course any nonreligious people.

The Court has re-created the impossible situation of the early 1800s: Schools will become excessively entangled with religion, and taxpayers will have to foot the bill. Teachers and coaches will take their paychecks and feel free to preach and pray. Families will take public tax money and spend it on private religious schools. The obvious problems will result from children who feel coerced to pray and from religious schools that teach anti-LGBTQ and creationist ideas, but the dilemmas are even broader. What about a teacher who offers optional test prep, with prayer being the cost of admission? What about a religious school that teaches that women and girls are inherently inferior and do not deserve education?

The religion-school culture wars of the early 1800s proved how impossible these questions would be, so Americans walled them off. That wall protected both Church and school. We’re going to miss it.