The archbishop of York's speech against equal marriage in the House of Lords on Monday represents another step in the Church of England's stumbling retreat on the issue, and does a lot to illuminate the reasons that it was defeated. I wrote "equal marriage" because the church has now accepted that gay marriage is coming, and that lasting gay relationships can be godly. It just wants to call them something other than marriages, and still feels this matters.

The archbishop, John Sentamu, asked: "What do you do with people in same-sex relationships that are committed, loving and Christian? Would you rather bless a sheep and a tree, and not them? However, that is a big question, to which we are going to come. I am afraid that now is not the moment."

No. It isn't. That moment passed years ago, when civil partnerships were first brought in, and the archbishop's was one of the loudest voices demanding that the Church of England have nothing to do with them. The bishops still don't realise what damage they did then.

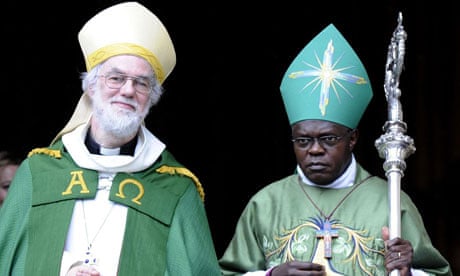

Even the supposedly liberal Rowan Williams said the other week, while lecturing on the fifth anniversary of his sharia speech, that "I am not wholly clear to what problem same-sex marriage is the answer" – at which my neighbour whispered: "He's an idiot if he doesn't know the problem is not listening to gay people."

So Williams is an idiot on this subject. And so is his colleague in York, and both for the same reason, very damning to Christians: they failed to listen to the weak because they thought the noisy bullies mattered more.

When civil partnerships came in, the two archbishops fought hard, along with the rest of the Church of England, to ensure that they had no religious or spiritual content at all. This was a monumentally stupid position for an established church to take, and the nation duly went ahead and injected its own spiritual contents, leaving the church looking like a whitewashed tomb.

Of course, it looks like frightful bad taste to say this now, flogging a dead horse and all of that. Yet I have a particular reason for doing so, and this is that the Cambridge college dean who married me and my wife, 25 years ago, was also the first Christian I knew to point out that the church should be marrying gay people as well as divorced ones, like me. "What we have to ask," he said, "is whether a gay couple can be a means of grace to one another."

In the late 80s this was still a startling question. The only out gay media person I then knew was Peter Ackroyd at the Spectator, and one of our colleagues there was a Sloaney woman who trilled "Have you heard about the miracle of Aids? It turns fruits into vegetables!" The Independent's sports desk had a bonding ritual involving elaborate homophobic abuse: "Sausage jockey? He's the Lester Piggott of the chipolata circuit," one man used to say who later became a celebrated liberal commentator.

Yet here was the dean of Trinity College, a figure at the heart of the established church and one of the very few Christian intellectuals I have known who kept his acts and his beliefs in harmony, telling me that equality was a Christian imperative. That was how the dons who then ran the church thought, and quietly acted.

But they never understood that power was passing from the dons, within the church as well as outside it. When the great evangelical backlash against gay people came in the 90s – culminating in 1998, when opposition to gay rights became one of the tests of orthodoxy within the Anglican communion and the main cause of its subsequent schism – the dons were all swept away. Williams, than whom no one could be more donnish, was also completely powerless in these matters, partly as a result of his own disastrous choices.

Retreating from the actual condition of the Church of England full of gay and tolerant people into a fantasy of an Anglican communion that had neither but would be "a global significant player" as George Carey once told the United Nations, the evangelical party made a church which could neither lead the nation morally nor even move with it and made instead a virtue of being out of touch. Looking at their church now, I remember Kipling's brutal epigram on a soldier shot for cowardice: "I could not face my death. This being known, / men led me to him, blindfold and alone."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion