In the aftermath of pandemic restrictions, Dr Joshua Edelman looks at how different religious communities across the UK adapted communal worship during Covid-19, and the lasting impact these changes have had upon clergy and worshippers.

As our society has opened up from the restrictions imposed by the pandemic, religious communities are gathering again in their churches, mosques, and temples for worship and community. But the experience of congregational worship without congregating for two years has left its mark, and religious groups across the UK have started to re-think the forms and methods they use in the digital age. What are the lessons from Covid-19 for communal worship?

The project Social Distance, Digital Congregation: British Ritual Innovation under COVID-19, which I led, looked at the experience of communal worship during the pandemic. This came from the understanding that communal worship with social distance – usually online – had to operate differently than the in-person rituals most of us were used to, and, therefore, it would feel different as well. Like a theatre maker who is suddenly forced to work on television, the new medium requires different skills, has different strengths, and may lead to different outcomes. As such, we were less interested in tallying how many people worshipped online, and more in understanding what that experience was like. Changes like this tend to stay around, and the clergy we interviewed said that they expected to keep using techniques they learned during the pandemic once it was over. We have in fact seen that happen, and so what we were studying was not just a temporary change in religious life that would be undone as soon as the virus went away, but a major shift in the way that people engage with religious community and ritual life.

The study made use of surveys, detailed case studies, and a regular focus group of religious professionals. Our findings, which you can read more about in the report, showed the creative and innovative ways in which religious communities kept their essential work going during a crisis unlike any of us had experienced before. But it also demonstrated several patterns in how different communities responded to the pandemic. As we move forward, and as more communities try to incorporate what they learned from the crisis into their ongoing life, these patterns are worth discussing.

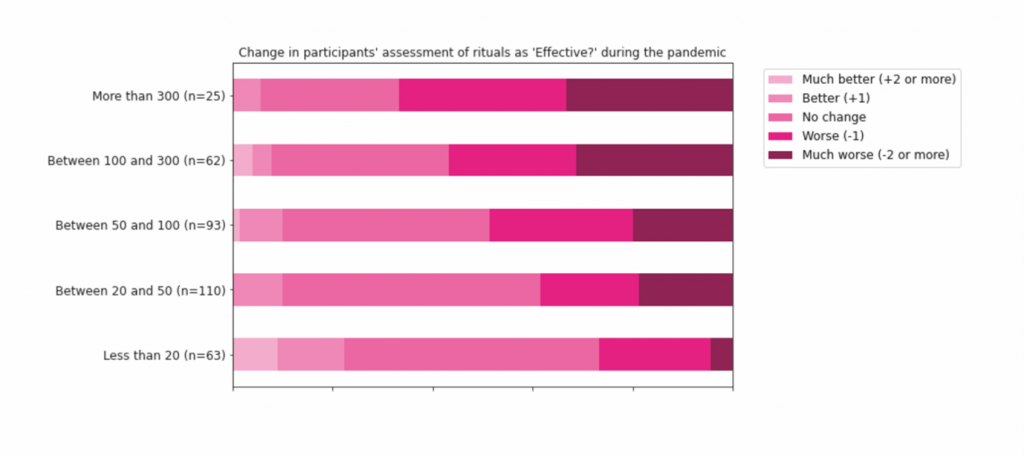

First, we found that, almost across the board, smaller communities had a much better experience of the pandemic than larger ones. The chart below (fig. 1) shows how religious participants assessed the effectiveness of their community’s rituals during the pandemic, broken down by size of community. The light colours on the left show those for whom rituals during the pandemic were much better (two points or more on a five-point scale) than those before; the dark colours on the right show those for whom it was much worse (again, two points or more). It’s only the smallest communities – those who ordinarily have fewer than twenty participants at weekly worship – for which the pandemic was a properly mixed bag; the larger the communities get, the worse the ritual experience during the pandemic tended to be.

This makes sense in the context of some of our project’s other findings: that it was a sense of togetherness – of being together and worshipping together – that was most important for pandemic worshippers, not the highest quality of streaming or exact ritual rigour. Smaller communities tend to be those with more limited means to put on a polished show online, without sophisticated cameras and microphones and editing. They also tend to be those where everyone takes some responsibility for keeping things running; there’s less likely to be a full-time professional who can organise everything on their own.

What we found was that this sort of practice tends to correlate with a sense of participation, inclusion, and engagement, and that this was more important to people than the professional polish of their worship. Small communities were better able to provide this. Many of the clergy we interviewed found this very reassuring. They were worried that, with geographical boundaries erased online, many congregants would flock to large, cathedral-like institutions which had choirs, organs, spectacular interiors, and the financial and technical wherewithal to put out a service that looked smooth and professionally produced. After all, most worshippers used the same device to stream their services as they did to stream Netflix. But this did not seem to happen. While worshippers did visit these extraordinary houses of worship online, they rarely stayed there. The lure of community was more important than the quality of the show. The fear many clergy had that online worship would encourage religious consolidation into fewer and fewer larger houses of worship does not seem to be borne out by our data.

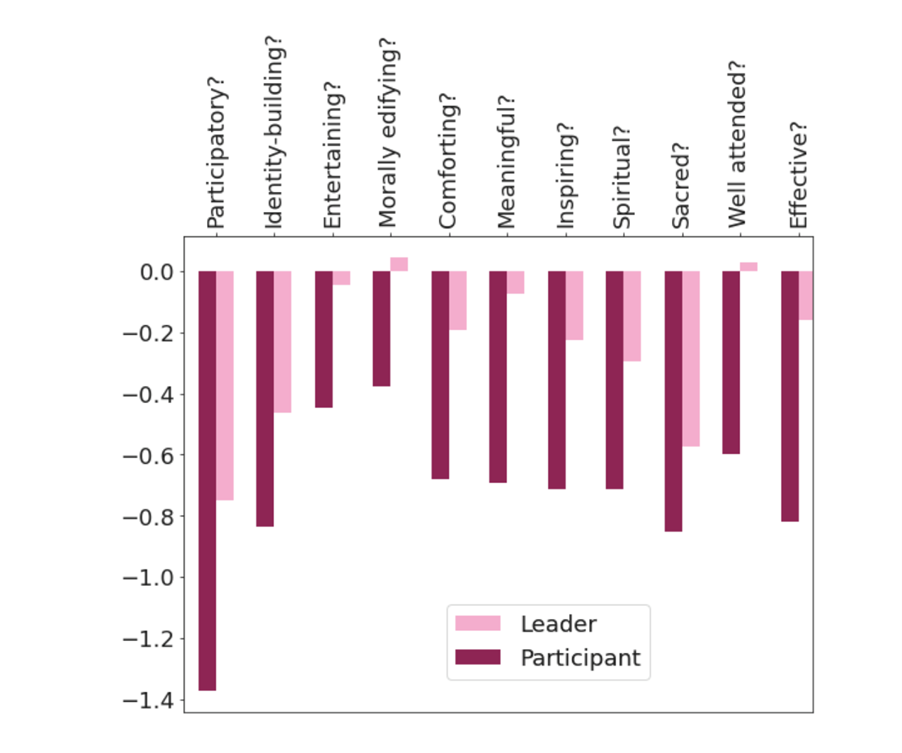

We also found worship via conference call software (such as Zoom) tended to give a more positive experience for worshippers than using streaming services (such as YouTube), even though it often led to more technical problems with sound and image. What was interesting, however, was that this difference was far less for clergy. There’s a logic to this – service leaders have more control over a live stream than they do a Zoom call – but it also leads to another of our findings, which was a disconnect between the experience of clergy and worshippers during the pandemic.

In and of itself, it is not surprising that those responsible for leading communal worship have a different experience from those who only participate in it. We observed other differences as well, between worshippers of different ages, locations, faiths, and so on. None, however, were quite as stark or surprising as the gap between leaders and congregants, especially within the Church of England.

This chart (fig. 2) shows how much Church of England clergy and members said their experience of ritual declined during the pandemic on each of the listed factors. (Again, this is measured on a five-point scale; the lower the bar, the larger the drop in experience). What jumps out is that while Church of England clergy seem to think that, on the whole, the pandemic was only a bit worse than normal, their congregants are far less happy. This is especially the case for some of those criteria which we tend to see as central to what ritual is: inspiration, meaning, spirituality, and (the most general term) effectiveness. We did not observe anything like this difference between clerical and lay experience for other churches, though most of them were far less represented in our sample than the Church of England for demographic reasons.

Why might this be the case for the Church of England only? It is hard to say, and while our interviewees were worried about this finding, few had a ready explanation for it. While this is a bit speculative, I’d suggest that, in many cases, Church of England clergy may have something of a different relationship to their congregants than other religious leaders do. Many of them were often conducting the same rituals in the same (architecturally beautiful) churches that they had been before the pandemic, and, despite the cameras, their experience did not change so greatly. Of course, this would be different for different communities, but the pattern was clear enough to be observed in our data.

More worryingly, though, it suggests a disconnect needs to be addressed between Church of England clergy and members. Clergy are not just worship leaders; they are pastors as well, and to do this pastoral work, they need a deep and rich understanding of the people they serve. Many of our interviewees noted the artificiality of studying the rituals of a religious community separate from all the other ways that community comes together. In the virtual age, community can more easily be freed from geography. This means that if a local religious community does not serve the needs of its members, it is easier for them to find another, effectively voting with their feet.

This makes it even more important that religious leaders understand and respond to the needs of their congregation. The opening up of the shapes and techniques of communal worship that the pandemic has facilitated will not be undone any time soon. Our research has shown that British religious leaders have the drive and creativity to address this, but it also has shown how difficult that task will be.

Photo by Gabriella Clare Marino

1 Comments