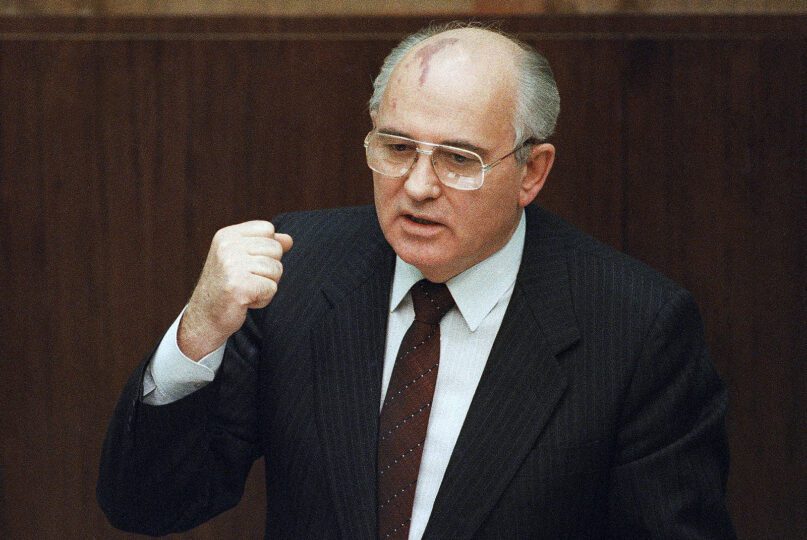

(RNS) — The legacy of Mikhail Gorbachev, so celebrated in the West, evokes deep ambivalence among Russians and Russian Orthodox believers. After 70 years of persecution and marginalization under the Soviet regime, the Orthodox Church took advantage of Gorbachev’s invitation to reenter public life.

But the last Soviet leader also failed the church in many Orthodox eyes. He reduced religion to a private, individual matter; tragically, he could not see Russian Orthodoxy as the politically privileged religion of both Russia and its Eastern Slavic neighbors. The position that he rejected has now helped Russians justify the invasion of Ukraine.

The Russian Orthodox Church was once the church of Russia and Ukraine. Under Gorbachev, Ukrainian Greek Catholics and adherents of an autocephalous — independent — Ukrainian Orthodox Church came out of the underground, eventually demanding legal status and the return of church properties the Communists had confiscated and given to the Russian church. Gorbachev made the mistake, his Orthodox critics charge, of applying glasnost and perestroika to religious affairs, rather than securing the unity of the nation and its historic church.

RELATED: How Putin’s invasion became a holy war for Russia

Gorbachev did not immediately reverse the government’s anti-religious policies when he came to power in March 1985. After the 1917 October Revolution, the new Soviet rulers razed churches or turned them into factories, gymnasiums, apartment buildings and warehouses. Church bells were not permitted to ring, nor could the martyrs of the gulag be canonized. Candidates for the priesthood had to be vetted by state religious affairs officials and security forces. Most monasteries were closed.

State authorities restricted religious activities to the remaining church buildings — educational endeavors or social ministries were forbidden. Attendance at religious services would often result in difficulties at work or school. At Easter, the police surrounded churches and demanded to see people’s passports. Religion increasingly became a matter best left to the babushki.

The church’s fortunes rose and fell in the following decades. Stalin relaxed anti-religious measures in exchange for the church’s support in the war against the Nazis, but Nikita Khrushchev, Stalin’s successor, pressed an aggressive campaign for atheistic indoctrination. Then, in 1983, in anticipation of Russian Orthodoxy’s celebration of its millennium in 1988, the government returned Moscow’s historic Danilov Monastery to the church.

But by the beginning of the Gorbachev era, fewer than 7,000 Orthodox parishes were in operation, compared with 50,000 in 1917. Only a couple of dozen of small monastic communities persisted, whereas there had once been a thousand.

Although himself a confirmed atheist, Gorbachev believed that Orthodox Christianity could counter the widespread demoralization and atomization of society that had occurred under communism and that Gorbachev was fighting with his perestroika and glasnost policies.

On April 29, 1988, an unprecedented meeting of church and state took place at the Kremlin: Gorbachev spoke for 90 minutes with Patriarch Pimen, acknowledged the Soviet state’s historic “mistakes” toward the church and promised a new era of religious freedom. The preceding months had already seen dramatic changes. Two major monastery complexes had been returned to the church, and the Easter liturgy had been broadcast for the first time on Soviet television.

Now, the rate of change accelerated. In June, Gorbachev’s wife, Raisa, and leading government officials attended the church’s jubilant millennial celebrations. By the end of the year, the church had established 800 new parishes, constructed dozens of church buildings and recovered the church’s most ancient monastic complex, the Monastery of the Caves in Kyiv.

It was a heady time. Orthodox priests began appearing regularly on television. The charismatic Orthodox priest Alexander Men attracted crowds of 15,000 in stadiums for his lectures on the Bible and religious life. Parishes organized Sunday schools and educational institutes. As the state-controlled social security net became increasingly frayed, Orthodox lay brotherhoods and sisterhoods stepped into the breach. Hospitals, orphanages and alcohol and drug rehabilitation centers, once off-limits to believers, flung open their doors, thankful for the church’s charitable work.

Over the objections of many local officials, church leaders now felt free to appeal to Gorbachev to defend their rights. By 1991, the church had more than 10,000 parishes and close to a hundred monasteries. Shortly before the demise of the Soviet Union in December of that year (and the end of his presidency), Gorbachev succeeded in passing a law of religious freedom and conscience that resembled the American model of separating church and state.

One church leader exclaimed: “The church is completely free for the first time in its history. The question is whether we will use this freedom.”

Gorbachev regarded the new law as one of his crowning achievements. The problem for many Orthodox believers was that the church now had competition. Dozens of “sectarian” groups emerged, including Jehovah’s Witnesses and Muslim “extremists.” Western evangelical missionaries poured into the country, as though Orthodoxy had never been truly Christian. In Ukraine, religious tensions intensified between the “Moscow church” and nationalistic Orthodox believers.

This loss of ecclesiastical empire came as inflation soared, the gross national product crashed, the Yeltsin government gave away state enterprises to oligarchs, and corruption became a way of life. A counterreaction soon set in, in political and religious affairs.

But even as freedom of religion and conscience became more restricted, the church won a privileged place for itself. With Vladimir Putin’s support, the church has grown to 39,000 parishes and 800 monasteries. It claims the affiliation of 70% or more of Russians. Many of them now associate Gorbachev with the efforts of the West to impose its “moral decadence” on the East. These are the Russians who welcome Putin’s “special military operation” to preserve Russia’s cultural and religious unity with Ukraine, where the fate of 12,000 of those parishes hangs in the balance.

After his death on Aug. 30, Russian Jewish, Islamic and evangelical Christian leaders commemorated Gorbachev enthusiastically for having given their adherents freedom to emigrate, undertake pilgrimages and manage their own affairs. Conservative Orthodox commentators had only scorn: “No other leader in Russia’s thousand years voluntarily gave up half of the country,” said one. Another asserted that Gorbachev was “weak and insignificant not only by historical but also by human standards.”

RELATED: How the war between Russia and Ukraine is roiling the faith tradition they share

The silence of Patriarch Kirill — who has justified the Ukraine invasion on Russian political and ecclesiastical grounds — has been telling. He has issued no statement, offered no condolences. A year ago, he congratulated Gorbachev on his 90th birthday and acknowledged, even if just matter-of-factly, Gorbachev’s efforts “to improve the situation of believers.” Now, the war has apparently made even ambivalence impossible.

Nevertheless, what happens in Ukraine will determine not only Gorbachev’s legacy in Russia but also the future of its church. Thanks to the atheist Mikhail Gorbachev, Orthodox art, architecture, music, ministry, spiritual life and social service could flourish again. Today, a Western observer can only hope that Kirill and his flock will not betray the remarkable freedom for which Gorbachev fought.

(John P. Burgess is James Henry Snowden Professor of Systematic Theology at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary and the author of “Holy Rus’: The Rebirth of Orthodoxy in the New Russia.” The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)