When you think of Martin Luther King Jr., what comes to your mind?

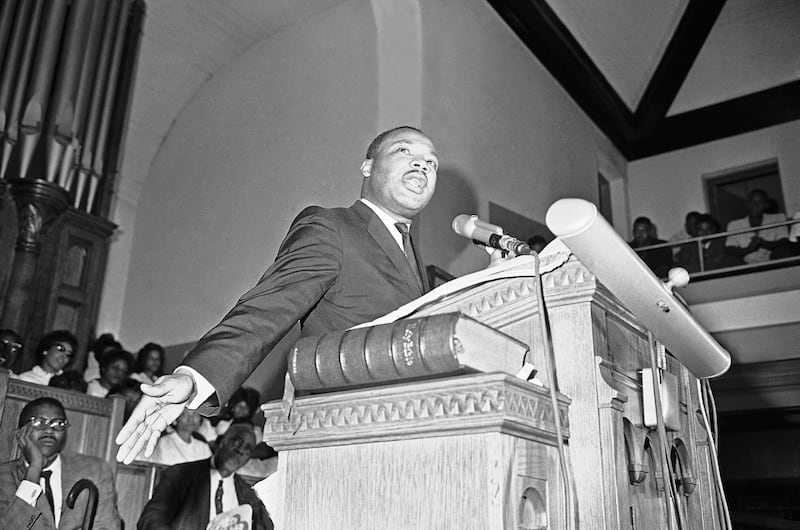

For most Americans, it’s likely the marches and speeches — the times when he brought his passion for civil rights to the streets.

But the public activism for which King is so well known wouldn’t have been possible without the quieter moments he spent away from the spotlight studying his Bible and serving in churches. His religious upbringing and work as a pastor shaped him into the unforgettable leader he was to become, experts say.

Martin Luther King Jr.’s religious upbringing

Martin Luther King Jr. was born on Jan. 15, 1929, in Atlanta. At birth, his given name was actually Michael, but his father later changed it to Martin to honor the famed religious reformer Martin Luther, according to Time.

King was raised in a highly religious household under the watchful eye of the Rev. Martin Luther King Sr., who served as pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church.

“Each day began and ended with family prayer. Martin was required to learn scriptural verse for recitation at evening meals. He went to Sunday school, morning and evening services,” Time reported.

In his autobiography, King praised his parents for raising him in a loving home.

“It is quite easy for me to think of a God of love mainly because I grew up in a family where love was central and where lovely relationships were ever present,” he wrote.

According to his autobiography, King officially joined Ebenezer Baptist Church at age 5. He admitted in the book that he joined mostly because his sister was joining, but added that church had always felt like a second home.

“As far back as I can remember I was in church every Sunday. My best friends were in Sunday school, and it was the Sunday school that helped me to build the capacity for getting along with people,” he wrote.

When did Martin Luther King Jr. get ordained?

Although King had strong ties to the ministerial profession — his father, uncle, grandfather and great-grandfather were all preachers — he did not always plan on becoming a pastor

As a child and then a teenager, King considered being a fireman or a doctor. Eventually, he became pretty confident he’d become a lawyer, he told Time.

As a student at Morehouse College, King wrestled with the role faith would play in his adult life. In his autobiography, he describes struggling to wed his love for research and intellectual debate with his love for the church, which, at least at that point in his life, seemed to him to run on emotion rather than intellect.

“I had been brought up in the church and knew about religion, but I wondered whether it could serve as a vehicle to modern thinking, whether religion could be intellectually respectable as well as emotionally satisfying,” he wrote.

It wasn’t until he took a college course on the Bible that he resolved the perceived tension.

“Two men — Dr. Mays, president of Morehouse College and one of the great influences in my life, and Dr. George Kelsey, a professor of philosophy and religion — made me stop and think. Both were ministers, both deeply religious, and yet both were learned men, aware of all the trends of modern thinking. I could see in their lives the ideal of what I wanted a minister to be,” King wrote.

He added that his father also played a big role in his decision to enter the ministry.

“My admiration for him was the great moving factor. He set forth a noble example that I didn’t mind following. I still feel the effects of the noble moral and ethical ideals that I grew up under. They have been real and precious to me, and even in moments of theological doubt I could never turn away from them,” he wrote in his autobiography.

King went directly from Morehouse College to Crozer Theological Seminary. While enrolled there, he studied the writings of a wide range of pastors and activists, including Gandhi.

After he graduated from Crozer in 1951, King continued his theological education at Boston University. While working on his doctorate, King deepened his understanding of nonviolent activism, according to his autobiography.

King launched his preaching career while he was still a student, serving as an associate pastor at his father’s church, Ebenezer Baptist in Atlanta, despite spending most of the year out of town.

When he had nearly completed the doctorate program at Boston University, King agreed to become the full-time pastor at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama. It was there that his life as a civil rights leader began to take shape, according to Christianity Today.

“In December 1955, a young Montgomery woman named Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to relinquish her bus seat to a white man. Local pastors rallied the black community for a city-wide bus boycott, named themselves the Montgomery Improvement Association, and unanimously elected King as president,” the article said.

How did faith inform Martin Luther King Jr.’s civil rights work?

The success of the Montgomery bus boycott turned King into a national figure. He suddenly had opportunities to speak at events across the country and a big enough following to help launch the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which coordinated the work of civil rights groups across the South, Christianity Today reported.

As the 1950s drew to a close, King left his post at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church and became co-pastor of Ebenezer Baptist in Atlanta. His preaching career continued to anchor his public activism, but he had less and less time to spend with his church.

Today, King is more often remembered for the speeches he gave at marches and other public events than for his sermons, but the faith leaders who worked alongside him or drew inspiration from him say you wouldn’t have had the speeches without the lesser-known church work.

Personal faith, as well as deep knowledge of the work of religious thinkers from the past, was at the root of his activism, said Rabbi Barry Schwartz, author of “Path of Prophets: The Ethics-Driven Life,” to the Deseret News in 2018.

“It’s legitimate to quote him in the most general of ways, but I don’t think we should forget that he was an example of religious faith at its best,” he said.

To fully appreciate King’s civil rights work, you have to grasp the role religion played in his life, Rabbi Schwartz added.

“He was motivated by general ideas of justice, but, at the same time, he was coming from a Judeo-Christian perspective,” he said.

alt=Kelsey Dallas

alt=Kelsey Dallas