(RNS) — In a survey of nearly 500 South Asian immigrants in the U.S., nearly half (48%) reported experiencing physical domestic violence in their lifetime, according to a 2021 study published in the Journal of Interpersonal Violence and cited by survivor advocacy organization South Asian SOAR.

And physical violence is only one form of abuse South Asian immigrants, both men and women, report experiencing at home. Nearly 4 in 10 say they have experienced emotional abuse (38%), and more than one-third report economic abuse (35%). Other commonly reported forms of domestic abuse include verbal (27%), immigration-related (26%), in-laws related (19%), and sex abuse (11%).

Bringing attention to the pervasive issue of domestic abuse within the South Asian diaspora has been the focus of an increasing number of survivor advocacy organizations, with many of them founded and run by South Asians, who argue the cultural context is important for understanding, addressing and preventing domestic abuse. Ultimately, they believe ending intimate partner violence in the South Asian diaspora must happen from within.

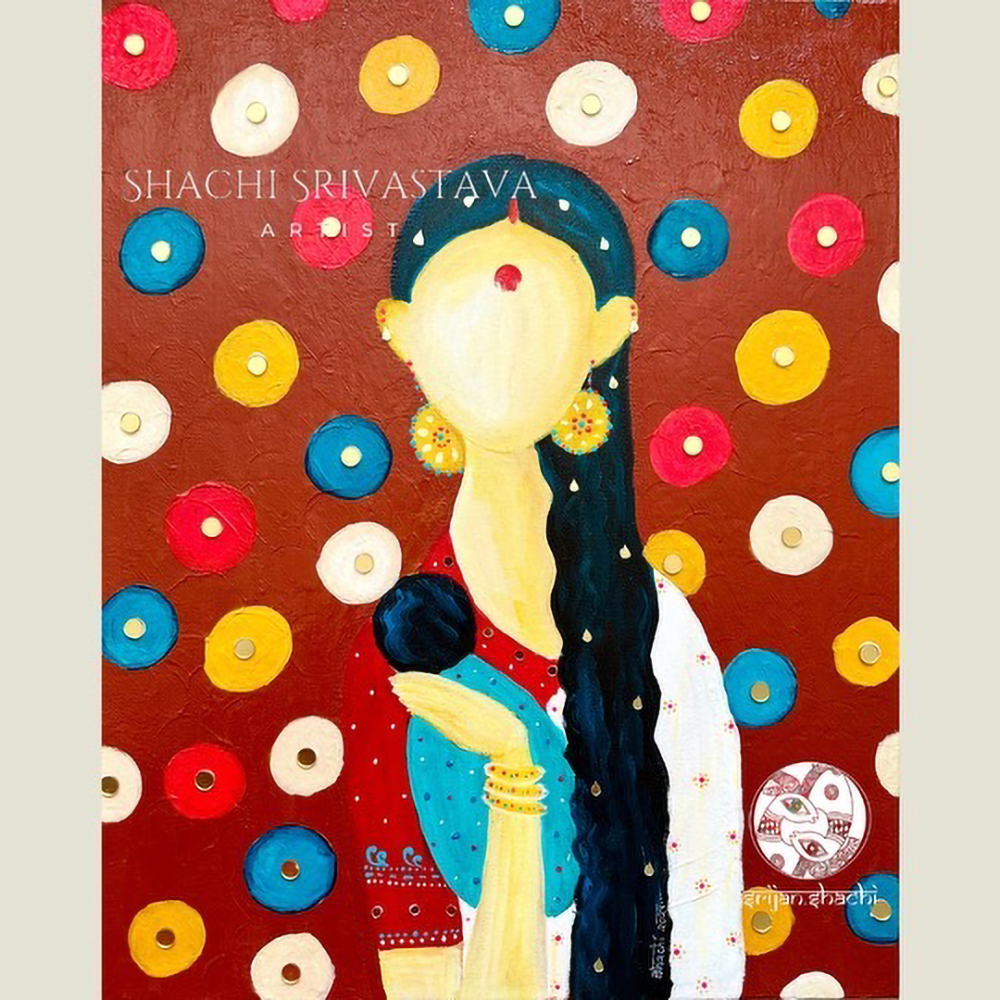

“When I hear about other women’s stories or children’s stories, it affects me a lot,” said Shachi Srivastava, an immigrant from India based in Atlanta. “Thinking about them, even though I don’t have any connection with them, I feel like it is our duty to help.”

At an art show titled “Unsung Unseen: Stories of Hope, Courage, Resilience” held by the nonprofit Raksha on Saturday (April 27), Srivastava, a folk artist, displayed the portraits closest to her heart: those of the mothers, the nurturers, who would do anything for their children.

Raksha, an Atlanta-based nonprofit for South Asian survivors of sexual abuse or family violence, is one of the many culturally specific advocacy organizations working to highlight survivors of domestic violence during Sexual Assault Awareness Month.

The expansive South Asian diaspora comprises a multitude of religions, languages and nationalities. Yet among them all, say those in the field, like Aparna Bhattacharyya, is a common roadblock: the particular cultural stigmas that keep survivors of domestic violence silent.

“We have to drop the judgment and be able to support our communities when they make a step to leave a violent relationship,” said Bhattacharyya, the executive director of Raksha. “We have to be aware of our own biases when it comes to who we think uses violence and who we think is impacted. Because it can be your best friend, it can be you, it can be any single one of us.”

Bhattacharyya, an Atlanta native, commonly sees in her work a story of ostracism: a woman who has left her abusive partner will be disinvited from social events, taking away her sense of community. “Oftentimes the person who is using the violence still gets to go to all the parties, and still has the status,” she said.

It was hard for Bhattacharyya to see past this in her own community, where she thought most people were more concerned with “what people are wearing to this religious function” rather than true support of victims of abuse. She thought South Asians “just didn’t get it,” or worse, condoned the violence.

But since joining Raksha in the late ’90s, Bhattacharyya has found the people who are working to break these stigmas of shame.

“Our community needs to start figuring out ways for us to dismantle the cultural beliefs that continue to tell us that we have to stay in unhealthy relationships, or that marriage is the only way, or it’s our duty to focus on marriage for our children,” she said. “No. Our duty is for us to be the best person for our children.”

The value of marriage, and consequently, the idea of staying in a marriage no matter what, is a tenet that connects many South Asians across religious cultures, says Bhattacharyya. Abusers may use religion as a tool of control, telling their partners: “You’re not a good Hindu, Muslim, Sikh or Christian if you want to get a divorce.”

And oftentimes, she says, survivors are hesitant to leave their family units, especially after being advised by their imams or pandits to stay. What’s more, says Zakia Afrin, the director of survivor advocacy for Bay Area-based survivor organization Maitri, the American legal system may push victims of abuse toward court, and eventually divorce and a tumultuous battle for child support.

These reasons are why, Afrin says, culturally competent care is especially necessary — and proactive. In late April, to mark National Crime Victims’ Rights Week (April 21-27), Maitri hosted a virtual panel with SOAR and Daya, a South Asian survivor organization in Houston, titled “Domestic Violence Homicides in the South Asian Community.”

Citing rising domestic homicide rates within immigrant communities, the panel shared insights on serving the South Asian community specifically and the need for preventative measures, including education and awareness within the diaspora, as well as a rapid response toolkit for working with survivors seeking help.

“Clients often ask us: ‘I don’t want to do any of this. What else can you offer me?,'” said Afrin. “Maybe she doesn’t believe that she’s ready to get a divorce and move on, that she needs to be a housewife. And that’s her choice. We always meet clients where they are.”

Afrin says faith is the No. 1 driver of decisions for her clients in times of despair, whether it’s the Hindu belief that karma from a past life determines our fate in this one, or a Muslim belief that what happens is a punishment or test from a higher power. But the goal of secular organizations such as Maitri, she says, is to provide a holistic perspective that respects and takes into account the family’s faith, as well as the law and the well-being of a survivor.

Importantly, says Afrin, many of her clients are first-generation immigrants, oftentimes with low English proficiency, who need a place to turn that understands the intricacies of coming from “a different culture with different experiences and expectations.”

“Being an immigrant is already traumatic in itself,” she said, “let alone having the biggest threat come from the person you trust and love and maybe even who you left your comfort zone to be with.”

And on top of this trauma, says Afrin, is a deeper social requirement to present a certain way.

“An immigrant family is often under so much pressure to be a success, and to give out that impression of success in the diaspora or larger community,” added Afrin. “Many times we push these issues under the rug and we don’t want to address it, almost like sacrificing oneself for the betterment of the family or the community as a whole.”

“We can’t just put it on the side and move on to whatever we think is our immigrant dream.”

For many advocates like Bhattacharya and Afrin, the blanket idea that South Asian immigrants are widely successful is inaccurate. But even more so, the perception that only those of lower socioeconomic status experience abuse. According to Aparna Asthana, director of development for Daya, experiences with domestic violence are just as varied as the diaspora itself.

“Not everyone in our community is a doctor or engineer, and not everything in our community is perfect,” said Asthana. “There are families struggling that need the support. But when I go out and talk to people, they say ‘it doesn’t happen in families like ours,’ and that’s not true at all.”

Many of Daya’s clients are from well-to-do families, she says, which may make it even harder for victims, especially young people, to come forward. “Our work is sort of empowering them to think beyond ‘What will the community think?'”

And often, says Asthana, violence between partners can be financial rather than sexual or physical — for example, when an abusive husband is the one with a work visa that doesn’t include his spouse, and he controls both the money and citizenship status of the victim. “Sadly, when I talk to older generations, they still sort of hold on to this idea that it’s not really domestic abuse,” she said.

People attend a 35th anniversary gala for Sakhi on April 26, 2024, in New York. (Photo courtesy of Shruti Bramadesam)

Kavita Mehra, the executive director of Sakhi, a long-standing survivor-focused organization in New York City, says it is up to other South Asians to break these cycles within their own families.

“Through the force of intergenerational trauma, family systems have become more in tune with silencing, ignoring and shaming those who have experienced violence,” said Mehra, who joined the organization shortly after 9/11, when “violence increased against any South Asian presenting person.”

“Because that becomes ingrained within a family system, breaking away from it becomes all the more difficult,” Mehra added.

Sakhi celebrated 35 years on April 26, marking the occasion with a grand gala with guests including actress Poorna Jagannathan and rapper/singer Raja Kumari. But at the heart of it all, for 35 years, says Mehra, have been the resilient survivors.

“For so long, the conversation about gender-based violence is to often imagine the individual within the midst of their crisis and trauma, and to look at them in that light,” she said. “Well, if you look at anyone at the most worst moment in their life, of course you’re gonna have some sort of judgment and view on that individual. So by the sheer getting through it, whatever that looks like for a person, that in itself is powerful.”

And working within her own community, she says, has been the most rewarding aspect.

“Within every fiber of my being, I believe that we are doing the most important work for the South Asian and Indo-Caribbean diaspora.”