Why Would a Millennial Become a Priest or a Nun?

The Pope, the Lord, and Lena Dunham: voices of a generation?

It's the question that haunts everyone starting a career: What's my calling? Some refer to it as a vocation; others might call it a life purpose. If you're a mid-career professional charged with giving advice to terrified twentysomethings, you might resort to that dreaded graduation speech touchstone, "passion."

There are a few hundred young people across the country who have interpreted "calling" in perhaps the most literal way possible: By devoting their lives to the Church. The decision seems radical in the context of common stereotypes about millennials, a generation often accused of lack of discipline, skepticism bordering on snark, preference for a hook-up culture, and only the vaguest spiritual impulses. These millennials defy those clichés, taking lifelong vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience to God -- and to the Catholic Church, which, especially in their lifetimes, has been regularly plagued by scandal.

Taking these vows in the Roman Catholic Church can mean many things. Women can choose what's called contemplative life, living in a monastery and, often, remaining cloistered from the world. Others pursue an "apostolic" life, doing work outside of the convent in fields like education and health care and returning home to community life. Men can join a religious order like the Benedictines or the Franciscans, or they can become diocesan priests and lead local churches.

Sister Colleen Gibson, a 27-year-old in the second year of her formal training with the Sisters of St. Joseph in Philadelphia, took the quiz on a website during college to determine what the best path might be for her. "It's like Match.com, but for religious communities," she explained. After identifying some of the aspects of religious life that appealed to her, she clicked a box to send her answers to various orders that might be a fit. "The next morning when I woke up and opened up my inbox, there were 40 emails -- it scared me to death. It's like throwing red meat into a lion's den."

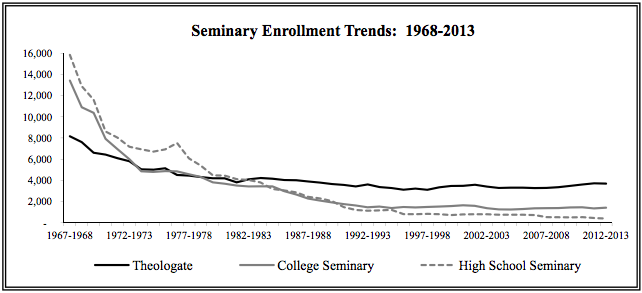

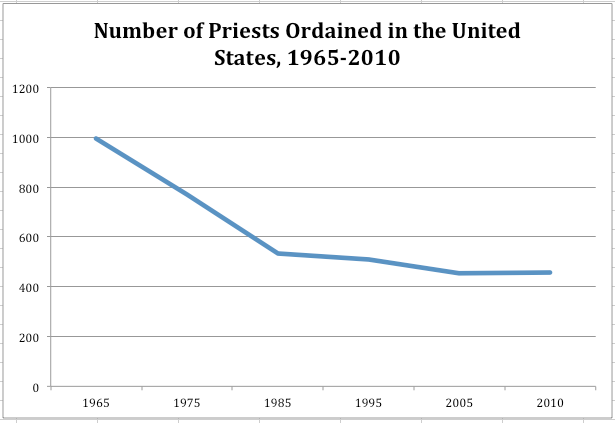

That's because the number of young people entering religious life in the United States is on a steep decline. Mark Gray, a researcher at the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA), explained that the number of men who start out at seminary and continue on to get ordained as priests has decreased dramatically over the last 45 years. Gray described this process -- deciding to enter religious life, going through seminary, and, finally, getting ordained -- as a sharp funnel that's getting sharper all the time. It's worth noting that some men remain part of formal religious life for their entire lives without getting ordained; these men are typically called "brothers" instead of "fathers."

But the new pope in the Vatican may give the priesthood a much-needed public relations bump. Although he was only elected in March, his work has already been surrounded with buzz: This summer, he made headlines by offering indulgences to those who followed his Twitter activity on World Youth Day and saying that it's not his place to judge "a gay person of goodwill who seeks the Lord." Some say that Francis is more human and easier to identify with than some of his predecessors.

"The majority of my family on my father's side are not Catholic," said 22-year-old Matt Ippel, who will join an all-male religious order, the Jesuits, later this month. "Sharing my upcoming plans, they've all been very excited and shown an immense amount of support, but they've also talked a lot about Pope Francis -- the way [he] has conducted himself in his conversations, his addresses, his homilies."

Danny Gustafson, a 24-year-old about to enter his third year of formal training with the Jesuits, has found it particularly meaningful that Francis is also Jesuit -- the first to ever become Pope, in fact. "It's been a great feeling of connection with the hierarchy, if for no other reason than because there's a shared formation that Pope Francis has that I'm going through right now. Knowing that the same spirituality that speaks to me speaks to the Pope -- I find [it] very humbling, but also very encouraging," Gustafson said.

"Who can predict what will happen?" said Father John O'Malley, a Jesuit who teaches at Georgetown and studies the history of the Church, when asked how Pope Francis might affect the number of young men entering religious life. "I must say, however, that I am a little optimistic."

And perhaps there's reason for Catholic clergy to be optimistic -- many Catholic millennials at least think about entering religious life. In a survey of non-married Catholics over the age of 14, researchers at CARA found that 12 percent of men and 10 percent of women respondents thought about becoming a priest, nun, or religious brother or sister "at least a little seriously." Millennials were also more likely to have considered joining religious life than people born between 1961 and 1981, who researchers called the "post Vatican II" generation.

Although it's harder to tell how many young women are entering religious life each year than it is to measure the number of young men pursuing priesthood, it's worth noting that the women joining more traditional orders are, in fact, young women.. Most of the religious orders of women in the U.S. belong to one of two umbrella organizations: The Leadership Conference of Women Religious (LCWR), which accounts for about 80 percent of orders, and the Council of Major Superiors of Women Religious (CMSWR), which accounts for the other twenty percent. The LCWR is generally considered to be the less traditional of the two -- for example, they have experienced tension with the Vatican over their silence on the issue of abortion. Women in CMSWR organizations are also much more likely to wear traditional habits, whereas most women in LCWR organizations wear street clothes.

But perhaps counter-intuitively, according to a CARA survey from 2009, 78 percent of women who join CMSWR organizations are under 30, compared to just 35 percent of those who join LCWR organizations.

"I will wear a habit -- that's my choice," said Toni Garrett, who, at 31, is about to start her formal training with the Sisters of the Holy Family of Nazareth. Most recently, Garrett worked as a vice president at Bank of America in Dallas, and for the past year, she has been working from home -- the convent. "[The habit] is attractive to me because I think that I need it. We have sisters who entered convent at 14, at 18, and have been sisters for 40, 50, 60 years. I've lived a pretty good portion of my life not in this way. For me, a habit is like a healthy reminder of who I've chosen to be."

No matter how traditional their lives become, however, these millennials still have millennial problems. For example, aspiring priests, nuns, and religious brothers and sisters increasingly face one of the great worries of their generation: student loans. In a 2012 survey, a third of religious orders and institutes reported that at least some people who had seriously considered joining their ranks decided not to apply because of educational debt. A fifth of those organizations reported financial strain from the debt of current or prospective members, and most shockingly, 70 percent of the organizations reported that they had turned away serious applicants because of their student loans.

Millennials who enter religious life are like their peers in another interesting way, too: They're more racially diverse. According to the 2009 CARA survey, 94 percent of the older women and men who have "finished" the process of joining a religious community by taking final vows were white, compared to just 58 percent of those in early stages. The next largest groups were Hispanic (21 percent) and Asian or Pacific Islander (14 percent).

Young religious "recruits" also fit into the mainstream image of millennial culture. Brother Jim Siwicki, a 59-year-old working with people who are considering joining the Jesuits, sees something distinctive about the new generation of novices. "There's a strong desire for a sense of community, both local and global," he said. But "the thing that's difficult that I see with millennials is that they want to keep all options open. It's not a lack of interest -- it's that fear of making a commitment."

Siwicki also noted that this generation is much more digitally inclined than some of the older Jesuits. "Sometimes I have to figure out who it is who's texting me," he admitted.

"I am a millennial, through and through," said Gibson, the young sister whose inbox was flooded when she expressed interest in becoming a nun. "There's a hunger within people for intentional living and intentional community... that crosses bounds. I don't see myself as turning my back on my generation. In bringing faith back to my generation and sharing it with people... It's trying to be in the culture, but not necessarily of the culture."

22-year-old Ryan Muldoon, who is about to enter seminary for the Archdiocese of New York, explained his choice in terms of discernment, a reflective process for understanding one's vocation, or purpose. "This isn't really a decision that anybody makes of their own volition. This really does stem from a deeper calling -- a call by God and a response by an individual," he said.

But the process isn't so different from any big decision twentysomethings have to make.

"Like an onion, there are various layers of discernment [and] what that word or process means to different people," Muldoon said. "The word 'discernment' does a great job of capturing what everybody, and young people especially in making big life decisions, is called to engage in."