Today Is the 50th Anniversary of the (Re-)Birth of the First Amendment

On March 9, 1964, a unanimous Supreme Court reversed a libel verdict against The New York Times in a case brought by Alabama officials who complained about a civil rights advertisement in the paper. The First Amendment, thankfully, hasn't been the same since.

Every person who writes online or otherwise about public officials, every hack or poet who criticizes the work of government, every distinguished journalist or pajama-ed blogger who speaks truth to power, ought to bow his or her head today in a silent moment of gratitude for a single United States Supreme Court decision issued 50 years ago today. It means simply that you can make an honest mistake when writing about a public figure and won't likely get sued.*

New York Times v. Sullivan, decided unanimously by the Court on March 9, 1964, in a decision written by Justice William Brennan, finally gave national force to the lofty words of the First Amendment, that there should be "no law... abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press." Without that ruling, and the precedent it has generated since (despite the efforts of Justice Antonin Scalia), investigative and opinion journalism as we know it today would not exist.

Much of the coverage of the 50th anniversary of the ruling, such as there has been, has focused logically upon its impact upon modern First Amendment law. But it is important to remember today that the case arose in the heat of the civil rights movement and that state libel laws, like the Alabama statute that the Court struck down, were routinely used as weapons by local officials to scare journalists away from covering the worst government excesses of that period.

It's also important to remember that until Sullivan, the First Amendment had traditionally been interpreted very narrowly. So narrowly, in fact, that the concept of libel was widely thought to be beyond constitutional purview. Let me put it this way (and I'm not the first to suggest this): If there were no Sullivan, there likely would not have been a release of the Pentagon Papers or a rigorous investigation into Watergate or much of any withering criticism of government that appears today in any medium.

The Story

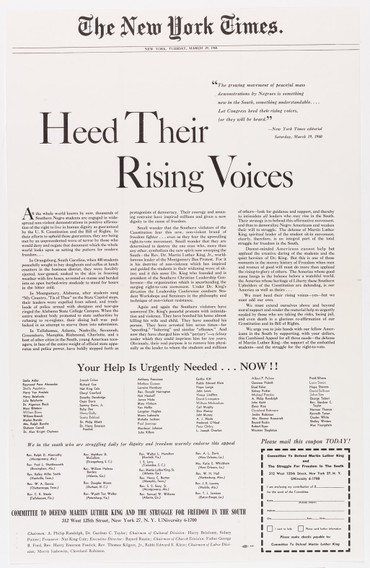

The story began in Montgomery, Alabama, on March 29, 1960, when a political advertisement appeared in The Times titled "Heed Their Rising Voices" criticizing Southern officials for their aggressive response to civil rights protests. The advertisement, signed at the bottom by civil rights leaders and others, was inaccurate in a few minor respects but it incriminated no Southern official by name. It appeared only once in the paper and it cost less than $5,000 to publish.

This did not deter L.B. Sullivan, the Montgomery Public Safety Commissioner at the time of the ad. First he asked the Times to make a public retraction to him. The paper did not. Then he sued the Times (and four black ministers who had undersigned it) under Alabama's broad libel law, arguing that they had defamed him and could not, because of the errors in the advertisement, successfully assert "truth" as a defense to the charge.

The state trial judge in the case was an unreconstructed Confederate and a Southern jury quickly came back with a $500,000 judgment against the defendants—a significant amount today that was even more significant then. The paper appealed the ruling to the Alabama Supreme Court, which in affirming the trial court ruling made the state's libel law, and thus the media's potential exposure, even broader still.

The trial judge had told jurors that the advertisement was libelous per se—that it was presumed to be libelous in other words. And both the trial judge and the state supreme court justices expanded the definition of the "malice" required in libel law to include, for example, "irresponsibility." The Alabama courts even implied that most any government official could sue for libel even if the public criticism was only directed at his or her office: "libel on government," it is called.

The Decision

The Supreme Court grabbed the case. The Alabama courts had quickly dispatched with the First Amendment defense The Times had asserted by declaring that it did not apply to libel cases. The justices in turn quickly dispatched with that position, which they declared would unlawfully "shackle the First Amendment in its attempt to secure 'the widest possible dissemination of information from diverse and antagonistic sources.'"

Justice Brennan wrote the ruling on behalf of a unanimous Court (there were two concurrences but no dissents). First he cited Judge Learned Hand, probably the most influential judge in American history never to have served on the Court. The First Amendment, Judge Hand had written decades earlier:

presupposes that right conclusions are more likely to be gathered out of a multitude of tongues than through any kind of authoritative section. To many, this is, and always will be, folly, but we have upon it our all.

Then Justice Brennan cited the language of Justice Louis Brandeis, another colossal figure in the history of the Court, in Whitney v. California. Justice Brandeis had written:

Those who won our independence believed . . . that public discussion is a political duty, and that this should be a fundamental principle of the American government. They recognized the risks to which all human institutions are subject. But they knew that order cannot be secured merely through fear of punishment for its infraction; that it is hazardous to discourage thought, hope and imagination; that fear breeds repression; that repression breeds hate; that hate menaces stable government; that the path of safety lies in the opportunity to discuss freely supposed grievances and proposed remedies, and that the fitting remedy for evil counsels is good ones.

Believing in the power of reason as applied through public discussion, they eschewed silence coerced by law -- the argument of force in its worst form. Recognizing the occasional tyrannies of governing majorities, they amended the Constitution so that free speech and assembly should be guaranteed.

Applying this analysis, the Court in Sullivan then framed the conflict this way:

Thus, we consider this case against the background of a profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open, and that it may well include vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasantly sharp attacks on government and public officials. The present advertisement, as an expression of grievance and protest on one of the major public issues of our time, would seem clearly to qualify for the constitutional protection. The question is whether it forfeits that protection by the falsity of some of its factual statements and by its alleged defamation of respondent (citations omitted by me).

Applying this standard, the Court declared that Alabama's libel law created a form of "self-censorship" by reporters (and also, notably, the "citizen-critic") that was inconsistent with First Amendment principles. A public official alleging libel would have to show "actual malice" on the part of the publishing defendant with "convincing clarity." To establish this, Justice Brennan wrote, a plaintiff would have to show either that the person publishing the material knew it to be false or published it after exercising a "reckless disregard" for its truth.

And as to the sweeping notion that Sullivan had been injured and was entitled to money damages because of the general criticism of "the police" in Montgomery, the justices held that: "no court of last resort in this country has ever held, or even suggested, that prosecutions for libel on government have any place in the American system of jurisprudence." This is why all of us can blast the Obama Administration, or the Bush Administration, without fear that some bureaucrat within those administrations will consider himself aggrieved enough to sue.

Even though the ruling was unanimous, there was drama behind the scenes at the Supreme Court—the last-minute decision by Justice John Marshal Harlan, for example, to join the majority decision, Justice Hugo Black, meanwhile, a First Amendment absolutist, wrote: "I vote to reverse [the Alabama judgment] exclusively on the ground that the Times and the individual defendants had an absolute, unconditional constitutional right to publish in the Times advertisement their criticisms of Montgomery agencies and officials."

Resources

The best work on the Sullivan decision is Make No Law, a book written in 1991 by the late, great Anthony Lewis, who was covering the Supreme Court in 1963 and 1964 for The Times. (Just think, for a moment, that those two terms alone would allow Lewis to produce his book on Sullivan as well as "Gideon's Trumpet," his masterpiece on Gideon v. Wainwright, the seminal right to counsel case decided almost exactly one year before Sullivan).

If you don't have time to read Make No Law, then go ahead and spend an hour now to listen and to watch Tony Lewis talk about it, and the Supreme Court, and the First Amendment, with Brian Lamb on C-SPAN. This is a conversation that tells us so much about each man, and about the case, and about the law and the Court 50 years ago. Every professor who teaches the first amendment, either in law school or to undergraduates, ought to play this video to students.

And if after listening to Lewis and Lamb talk about the case you want to get a true feel for the issues in play at the time—six weeks after the assassination of President Kennedy, months before the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964— go ahead and listen to the oral argument in the case from January 6-7, 1964, one of the more intense or passionate arguments you ever will hear (or see).

Finally, if you want to take a broader look at the context of the Sullivan case take the time to read The Race Beat, published, like Make No Law, in 1991. This book, written by revered journalists Gene Robert and Hank Klibanoff, helps us remember today all that was at stake in 1964 and how likely history would have been different had journalists back then been chilled from reporting the truth about the Southern response to the civil rights movement.

____________

* But that doesn't mean you still won't get in big trouble if you make a mistake reporting about a public figure. On Friday, for example, a state trial judge in New York permitted a libel lawsuit brought by Michael Skakel to proceed (at least a little further) against television personalities Nancy Grace and Beth Karas and show producers at Time Warner and the Turner Broadcasting System.