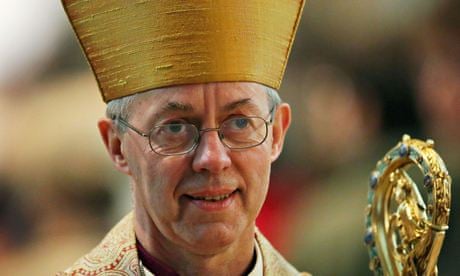

The Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, has put up a haunting video in which he talks of his experiences in South Sudan over a montage of clips showing corpses and grieving survivors. One shot shows Archbishop Deng, the leader of the Anglican church there, praying with the leaders of the two factions in an attempt to bring about peace.

To date 1.5 million people have been displaced by the civil war in South Sudan amid great savagery. When the clergy of the cathedral in Bor were killed in January, the women were all raped as well. It's worth noting that neither side in this war are Muslims. Both identify as Christians.

So what use can Christianity be to end the horror? Welby's first purpose is to urge viewers to prayer: "As we pray, we engage with God in the struggle against human evil," he says.

Is there another role for believers in all this? By coincidence, this question was debated in London on Wednesday evening, at the last of the Westminster Faith Debates. Jonathan Powell, Tony Blair's former chief of staff, and a man who spent years trying to bring about the peace agreement in Northern Ireland, was emphatic then that religion has little role.

"These conflicts are not about religion. They are about identity, and resources, and power," he said. "Even Boko Haram is not about religion. In modern days there is no such thing as a religious conflict, which is to say a conflict which is about religious doctrine."

Further, he said that religious leaders are not often helpful in peacebuilding, and certainly were not in Northern Ireland. Some individual religious professionals had made a difference but the denominational establishments had not.

What helped was contacts at the level below headline leadership. Powell praised the work of the Tony Blair Faith Foundation in Nigeria, which is bringing together mid-level clergymen and mid-level imams to talk. The point is not for them to agree – they won't – but that they can come to see each other as human.

This chimed with Welby's claim that religious believers are the ones who keep social networks alive in otherwise ravaged societies: again this is a matter of small-scale, face-to-face contacts.

The obvious objection to Powell's claim that conflicts concern identities, power and resources rather than religious differences is that religions are in fact largely concerned with identity. They function to locate us as individuals and to define the groups to which we belong. A religion that doesn't deal with identity is one that's dying.

I raised this problem from the audience and Powell's reply was subtle and fascinating. No one in west Belfast, he said, identified themselves by religion. Instead, their identity was more local, perhaps more political, and much more fine-grained. To paraphrase his answer, they might all be Catholics to the Protestants. But to themselves, they were Stickies, or from Andersonstown, or Provos. These are not theological or doctrinal distinctions.

This is similar to the way in which Scott Atran has dissected jihadist groups down to the level of football teams: the ideology is a banner, but what really motivates them is loyalty within a friendship group of young men.

I don't want to argue with these analyses. Powell knows a lot more than I do about peacemaking, possibly almost as much as the commenters here. But if they are correct, they raise the question of whether there has ever been a religious war. Even the Swedish intervention in the Thirty Years' War, which rescued the losing German Protestant cause and was about as close as European history has come to a jihad, was driven by some entirely untheological motives, and supported by Catholic France.

But if religion doesn't start wars, it's clear that it can make some conflicts harder to solve, as it has done in Israel and Palestine. Welby's video about Sudan is at the very least a determined effort to stop that happening. It's not glamorous but so what. Believers most often approach heroism when they are at their most boring.