The culture wars afflicting the Church of England are basically over. By the end of the summer, the General Synod will have agreed women bishops. And while the fight for full gay equality has some way to run, this one is substantially over too: not least because the demographics are pushing inexorably in a liberal direction. Young people, even evangelicals, don't see the problem. So Christian progressives like me ought to be celebrating? Well, not quite.

I'm writing from a cafe opposite the Storkyrkan, the cathedral of the Lutheran state church in Stockholm. It's a church with the world's first out lesbian bishop (she's in a civil partnership). The churches themselves are beautifully maintained, due to a church tax that most people can't be bothered to opt out of (66% of the population pay it). The gilded opulence of the Storkyrkan, with its front pews reserved for the royal family, tells of a cosy relationship between the church and the state. But regular churchgoing is negligible (only 2% of the population) and dropping. It's notable that the only thing about this beautiful museum of a church that needs fixing is its broken font, tucked away down a side aisle.

And yet, I am here to talk seriously with a group of actors in rehearsal for a play about religion. It's co-written by our own celebrity atheist AC Grayling, and directed by a secular humanist, a position that the actors all basically share. I find it fascinating that the darker existential themes of death and evil – even religion itself – are being so much more effectively confronted by the culture industry than the churches.

Much of this tone was set by the virulently anti-Christian Ingmar Bergman, whose father, against whom he reacted, was chaplain to the king of Sweden. But even for lower-brow stuff, such as Wallander and Stieg Larsson, it's Swedish art that seems to tackle the big questions of human darkness – the whole Nordic noir thing – while the churches feel, at best, like tasteful temples to nice and, at worst, like showhouses to establishment grandeur. Atheists seem to take the darkness of God far more seriously than Christians. People will queue up to sit through a disturbing six-hour play by Lars Norén at Stockholm's Dramaten theatre, but assume these grand churches – studded with "do not touch" signs – have nothing to say to them. And I totally get that.

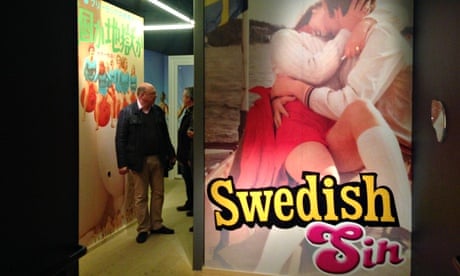

Elsewhere, down by the Stockholm waterfront, an exhibition devoted to "Swedish sin" has just opened at a trendy new gallery. It's terrific – a narrative of how Sweden came to be seen as sexually permissive. It was actors like Ulla Jacobsson in the 50s and Lena Nyman in the 60s that set the tone for the stereotype of skinny-dipping blondes enjoying outdoor sex. Then came the porn explosion of the 70s. But as the exhibition suggests at the end, it's alcohol not sex that is the real Swedish sin. The darkness is taken home. In an EU survey earlier this year, Sweden topped the European league table in domestic violence. Suicide rates are among the highest in the western world.

The takeaway message is this: no one needs churches to be nice or tasteful. If churches have a future, it's in addressing our existential darkness: sin and death. Progressive politics is important, but it doesn't do any deep religious work. And liberals in the church will have to rediscover this after we have won our culture wars. What other religion has such a dark image at its centre? And yet my own brand of liberal Christianity too often seeks salvation through a few gentle verses of All Things Bright and Beautiful or lots of self-important dressing up and wandering around in fancy churches. Devoted atheists are never going to be persuaded by a theology of the cross. But no one whatsoever is going to be persuaded by a theology of nice.

Twitter: @giles_fraser