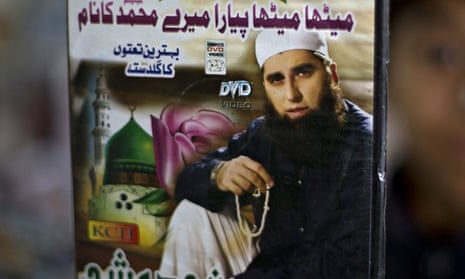

Rich businessmen, singers of patriotic pop songs and preachers with impeccably hard-line credentials are rarely among those accused of the deadly offence of insulting Islam in Pakistan. But Junaid Jamshed, a crooning evangelical Muslim being investigated by police under the country’s notorious blasphemy laws this week, is all three.

A household name who shot to fame in the eighties as the lead singer of the band Vital Signs, he later set up his own fashion empire and joined the Tablighi Jamaat, a group of itinerant preachers with an especially austere take on Islam.

With his typical Tablighi thick beard and shaved upper lip, Jamshed could not be more different from the profile of most alleged blasphemers: the poor, the politically unconnected and religious minorities.

In recent years such people have been accused of desecrating Qur’ans or insulting the prophet Muhammad with increasing frequency – often falsely and on the flimsiest of evidence. It is a crime punishable by life imprisonment or death, the latter either at the hands of the state or by enraged lynch mobs.

Such is the sensitivity of the issue, and fear of repeating an alleged blasphemy, that many in the local media skirted around reporting what Jamshed said during a recorded religious homily published on Facebook. The country’s bestselling English-language paper merely said he had been accused of “uttering shameful words against holy personalities”.

In fact, during his talk to a small group of men, Jamshed teasingly mocked Ayesha, one of the wives of the prophet Muhammad, while explaining his view about the inherent frailties of women. A story about Ayesha feigning illness to gain the attention of her husband “proves that a woman cannot be reformed even if she is in the gathering of the prophet”, he said.

The sexism of his remark annoyed some liberals. But his casual tone outraged the Sunni Tehreek, a national grouping of clerics who launched a sit-in in Karachi to demand Jamshed’s arrest on Tuesday. With the police initiating an investigation, Jamshed, who is said to be outside the country, issued a grovelling apology in an apparent bid to stave off arrest and trial.

Those accused of blasphemy struggle to defend themselves in lower courts where judges are often terrified of acquitting.

“Because of ignorance, lack of knowledge and naivety I said some extremely inappropriate sentences about the mother of the Muslim nation,” Jamshed said in an online video. “I beseech you, I beg you like a beggar, to forgive me,” he said, his voice cracking towards the end of the short video.

It was not enough for the Sunni Tehreek.

“We do not accept any apology because blasphemy against the prophet deserves the death penalty,” said a spokesman. “We have asked the administration to arrest him and produce him in court.”

Tariq Jameel, a senior member of Tablighi Jamaat, offered only a qualified defence. In a video statement he made clear the preaching organisation “had nothing to do with his mistake”.

Personal vendettas and petty disputes often lurk beneath the rising tide of blasphemy accusations and it seems Jamshed may have been caught up in the deadly rivalry between two schools of Islam.

The country’s majority Barelvis, which are represented by the Sunni Tehreek, have long objected to the efforts by hard-line Deobandis to recruit from their flocks, take over mosques and even attack the shrines of revered Sufi saints.

Barelvis have also shown themselves to be among the most implacable supporters of Pakistan’s blasphemy laws.

The laws are regularly criticised by international human rights groups, but commentators say they have almost no prospect of being reformed. They have also been blamed for encouraging attacks by lone vigilantes and mobs who take it upon themselves to beat up or kill people accused of blasphemy, or even their defence lawyers.

On Thursday it was revealed gunmen had on the previous night attacked the home of a lawyer working for a university lecturer accused of blasphemy in the city of Multan. Another lawyer working on the same case was shot dead in his office in May.

Some prominent Pakistanis are increasingly alarmed by the potential for blasphemy charges to be levelled against members of the country’s normally untouchable elite. In recent months there has been a rash of cases lodged against influential personalities.

In November a court in Gilgit-Baltistan sentenced to 26 years in prison a famous actress, a talk-show host and Mir Shakil-ur-Rehman, the country’s most powerful media mogul. One of Rehman’s television stations was found to have broadcast blasphemous material when it staged a re-enactment of a wedding between the starlet Veena Malik and her husband while a popular devotional song about one of the prophet’s wives played in the background.

Last week the Lahore high court ordered a blasphemy case against Sherry Rehman, a former ambassador to the US who once campaigned for reform of the blasphemy laws, to be reopened.

And in Karachi in October the supposedly secular Muttahida Qaumi Movement demanded a case to be opened against Syed Khursheed Shah, the leader of the opposition in parliament.

“It always used to be a law that people were ashamed or embarrassed to use at a higher level,” said one prominent politician, who did not wish to be named even discussing the subject.

“Now in the last three months we have seen four cases because there is no serious national narrative against extremism.

“This is now being openly used as an instrument to settle any kind of score,” the politician said.