Hanukkah With the Jews for Jesus

What it's like to be part of Messianic Judaism during the holidays—and how its ever-growing outreach organization has upped its evangelization efforts

Hanukkah parties can be measured in a few ways: the number of latkes present; the horribleness of the soundtrack, which inevitably includes small children singing about dreidels; the degree to which menorah-themed decorations have taken over. The get-together I attended last week at the Gottlieb household in Fairfax Station, Virginia, hit all these holiday standards, and more—they even had whitefish salad laid out on their festive blue-and-silver tablecloth.

The biggest difference between this party and all the other Hanukkah parties I've ever attended was the involvement of Jesus.

"I wanted to be a rockstar," said Val, one of the first women I spoke with, by way of introduction. "Then Jesus came into my life and said, 'Eh, that's not what I have planned for you.'"

Val was one of 30 to 40 people at the party, which is hosted every year by the Washington, D.C., branch of Jews for Jesus. Attendees identified themselves in lots of ways: Jewish believers in Jesus, Messianic Jews, Jewish Christians, and, sometimes, just Christians. Many worship together at the McLean Bible Church; for the most part, Jewish believers in Jesus go to evangelical churches, rather than synagogues.

But for one reason or another, everyone there wanted to participate in and learn about the rituals of Hanukkah, from lighting the menorah to telling the story of the Maccabees. There were babies, teenagers, and older single ladies; the group even included a couple from Iran, a black woman, and an Asian woman. Some grew up practicing Jewish traditions in conservative and Orthodox households; others had never seen a menorah before. Jews for Jesus exists for all these people—they educate Christians, and they also offer community to Jewish believers in Jesus.

But most of their work focuses on another kind of person: Jews, or rather, Jews who don't believe in the divinity of Christ. At this particular Hanukkah party, there was only one person who fit that description: me.

When Jews for Jesus was founded in San Francisco in 1973, it was called by a different name—Hineni Ministries, after the Hebrew word Abraham and Moses use to respond to God when he speaks to them in the Bible. "Jews for Jesus" was one of the organization's slogans, along with "Jesus made me kosher" and "if you don't like being born, try being born again," said David Brickner, the executive director of the organization, in a phone interview. "The media were the ones who glommed onto that slogan and started calling us the Jews for Jesus, and we thought, well, okay."

Brickner's background isn't typical of most people who identify as Messianic Jews: On his mother's side, he says, he's part of the fifth generation of Jewish believers in Jesus. Especially in the early days, Jews for Jesus was mostly made up of Jews who had starting believing in Jesus later in life. The Messianic Jewish community developed in tandem with the Jesus People movement, which was a kind of hippy Christian revival in the 1960s and 70s. Jews for Jesus offered ways for people to maintain a connection to their Jewish identity while embracing Christian spirituality.

Before Brickner took over leadership of the organization in 1996, it was led by its original founder, a Jew from Kansas named Moishe Rosen. Like Brickner, Rosen was an ordained Baptist minister; after going through a conversion in 1953, he made it his life's work to proselytize to Jews. Ultimately, this is the mission of Jews for Jesus: "We want to make the Messiahship of Jesus an unavoidable issue to our Jewish people worldwide," Brickner said.

To say the least, this was met with skepticism, particularly in the American Jewish community. For example: "'Hebrew Christians' Trouble Jews," declared The New York Times in May 1977. The author wrote that "the growth of such communities and their proselytizing have raised considerable anxieties in the Jewish community," and Rabbi James Rudin, then an assistant director at the American Jewish Committee, said "the Jewish attraction to the cults is a stunning indictment of our inability to relate to our youngsters on a spiritual level." The Times published 50 such articles mentioning Jews for Jesus or Messianic Judaism in the 1970s alone.

Stephen Katz, the director of the Jews for Jesus's missionary work in North America, became a follower of Christ around this time. When he was a first-semester college student, he was assigned to write a term paper on the Messianic expectations of Jews during the life of Christ. In the course of his research about Jesus's teachings, he told me at the Jews for Jesus Hanukkah party, "I started to lean toward it being true—which was threatening."

This word—threatening—comes up a lot in conversations about Jews for Jesus. Katz had been raised in a conservative Jewish household in Chicago; when his parents found out that he considered himself a follower of Christ, they were shocked. "My mother said I was brainwashed. My father said I was trying to put up wall between us. They had my uncle, who's a rabbi, come over and try to straighten me out," Katz said.

Their attitudes were specifically shaped by world events at the time, he added: In 1975, the United Nations passed a resolution determining that "Zionism is a form of racism and racial discrimination." (It was revoked in 1991.) "My mother said, 'Stephen, there's going to be a new wave of anti-Semitism in this country, and you're just trying to hide.'"

To Jews—and especially those who live in diaspora, or places other than Israel—the mission of Jews for Jesus can seem like an attack "from within": They evangelize by creating a sense of commonality and shared values.

But at least to some extent, the organization's leaders are aware of this perception.

"It's is a frontal assault on identity," Katz said. "Jesus is not only seen as foreign—[Christianity] is seen as destructive to Jewish identity."

Jews are a people long persecuted, often in the name of Christ. Proselytization is never just a high-minded exchanged of metaphysical worldviews—and to Jews, it can seem like an attempt to undermine the core beliefs and traditions that define their faith.

This can lead to hostility—and, sometimes, violence. "You might be spat upon, depending on what part of the world you're in," said Larry Dubin, the head of the Washington, D.C., branch of Jews for Jesus at the Hanukkah party.

"My wife was attacked a couple of times. One woman took her glasses and destroyed them. A Jewish man, much taller than she was, basically knocked her to the ground," he said. "She was proclaiming that Jesus, or Yeshua, is the messiah, and they didn't like it."

This, he says, is just "part of the business. The prophets were rejected. The messiah was rejected. Do you think people are going to say, 'Oh! It's Stephen Katz! Let's go see what he has to say'?

"It's been a battle of the ages."

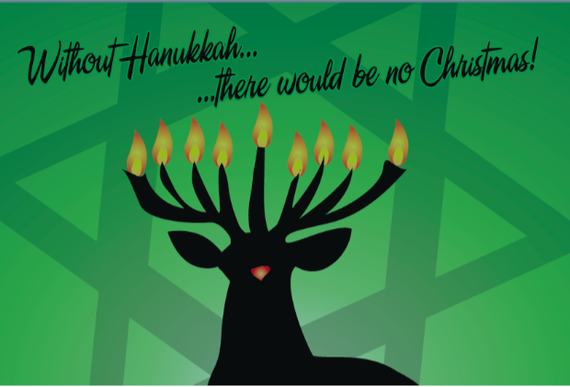

For all this hostility, Jews for Jesus still seems to have a good sense of humor about its work. This holiday season, its North American offices distributed cards that remix Hanukkah and Christmas—adding some Hebrew to depictions of the nativity, making a menorah out of Rudolph's antlers, that sort of thing.

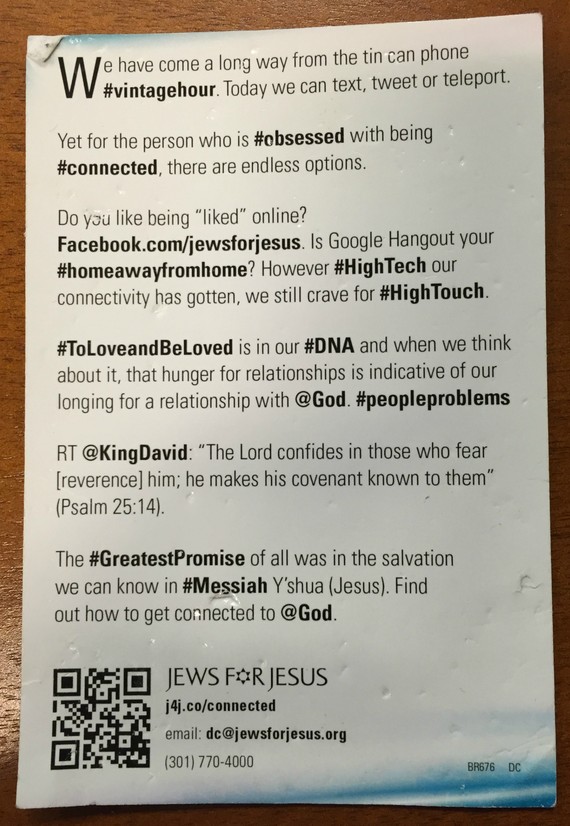

Humor seems to be the organization's schtick. This summer, I happened to pick up a flyer put out by the D.C. branch of Jews for Jesus, asking passersby whether they feel #connected with @God.

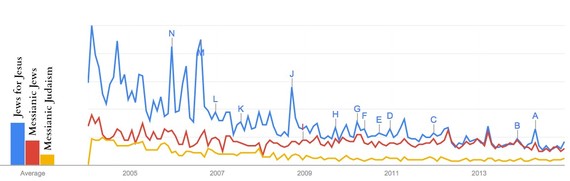

But for all its efforts to reach out to the young and the hashtag dependent ("Last summer we were trending on Twitter!" Brickner told me excitedly), the organization has seen a drop-off in engagement—and, to a certain extent, press coverage.

"Jews for Jesus was oftentimes seen in America as counter-cultural and rather intriguing to young Jews who were disaffected," Brickner, the organization's executive director, said. "It has more recently been seen as part of the wallpaper."

Or, a bit more tangibly: From the organization's founding in the mid-1970s until the early 2000s, there was a steady rise in the number of books that mentioned Jews for Jesus, Messianic Jews, and Messianic Judaism. But starting roughly ten years ago, that number plummeted.

That data, from Google ngrams, only extends through 2008. But according to Google trends, which traces search trends from 2004 forward, a similar pattern continued throughout the aughts, at least in terms of news headlines about Jews for Jesus, Messianic Jews, and Messianic Judaism.

Perhaps the novelty has worn off. This is what Brickner thinks, anyways—which, he says, is why the organization is now seeing its greatest successes in Israel, rather than the United States.

"There's probably a greater openness [in Israel]—in terms of attitude, and willingness to discuss the concept—than in any of the other 14 countries we're currently operating in," Brickner said. "There's a great curiosity about a whole host of things, spiritually. That's why you've got people, fresh from the Israeli army, going off to India and Nepal, following the hummus trail."

Of the roughly 200 staff members who work for Jews for Jesus across the world, about 30 of them work out of the organization's office in Tel Aviv. Although the organization sent its first missionaries to Israel starting in the spring of 1975, for 25 years, these were only short-term efforts. Then, in the summer of 2000, the Jews for Jesus received an amutah, or official government recognition as a non-profit organization. Since then, its Israeli operation has been growing—they've now got a second office in Beersheba, for example.

Of course, this alleged Israeli "openness" to Jews for Jesus is very different depending on which Israelis you're talking about. Katz called it "ambivalence"— there may be a sense of friendly curiosity among the secular public, but others have fought the presence of Jews for Jesus in Israel for reasons of religion or nationalism. For example, when the organization bought its offices in Tel Aviv, Katz said, the Orthodox, anti-missionary organization Yad L'Achim "posted everywhere, warning everyone to keep the missionaries away and complain to the municipality."

For organizations like Yad L'Achim, this is a matter of preserving faith, and numbers—"we don't give up on even a single Jew," their website blares. But for some of the modern Orthodox, the argument is more nationalistic, Katz said. "[People] say, 'We got this in Europe and elsewhere. We have one little piece of turf. Leave us alone.'"

The funny thing about holiday parties, though, is that it's very hard to look at people slurping latkes in dorky sweaters and see the complex, centuries-old tension between Christians and Jews.

I met Rachel, who grew up going to Messianic summer camp and got introduced to her husband through Jews for Jesus. Their baby, Micah, had hands sticky with the red sprinkles of what looked like a misplaced Christmas cookie.

I met Suzanne and her twentysomething daughter, Cassidy, who traditionally hit this Hanukkah party as their once-a-year bout with Judaism. After becoming a Christian at the age of 17, Suzanne didn't speak with any members of her conservative Jewish family for 20 years.

If it seems rude to ask strangers about decades-old family feuds at a crashed Hanukkah party, well, it is. But the people I met were remarkably willing to talk about their paths to believing in Jesus, and the pain that accompanied it. They also shot back questions: What faith was I raised with? How much had I been exposed to Christianity? Do I attend religious services?

Occasionally, when people heard I'm Jewish, they would "casually" suggest that I try reading the New Testament. Maybe in another context, this would have felt threatening. But it didn't. That is part of who they are, just as being Jewish in my own, complicated way is part of who I am.

Because identity is never clean, no matter who you are. We are all dorky people slurping food at holiday parties; we are all symbols of centuries-old religious tension.

During our conversation, Katz told me about a dinner party he attended at his parents' house in the mid-90s. His mom's friends kept asking him what he did for a living; at that time, he was managing a bookstore for Jews for Jesus in San Francisco. He followed his mom into the kitchen during a lull in the meal.

"I don't want to embarrass you and dad in front of your friends," he told her.

"And my mom's response was, 'Oh Stephen, don't worry about it. I mention that you're with Jews for Jesus all the time,'" he said.

"Before that, I didn't realize she had reached that point of comfort with what her son is."