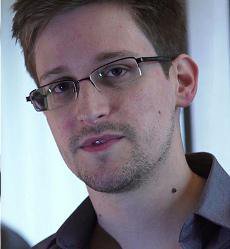

Edward Snowden could only speak to the committee by video link. Flickr / Robert Douglass. Some rights reserved.In recent weeks, parliamentarians specialising in legal and human rights from the 47 member states of the Council of Europe have sent a strong signal in favour of upholding privacy rights in the face of the threat of terrorism.

On 26 January, the Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) unanimously adopted a draft resolution, ‘Mass surveillance’. Work on this report had started in the summer of 2013, when the whistleblower Edward Snowden first revealed the extent to which the US National Security Agency (NSA) and others were spying on everyone and everything.

The committee invited Snowden to testify before it in Strasbourg in April 2014. Unfortunately, he was unable to attend in person as he could not be given the required guarantees of his safety and freedom, in the face of the strong wish of the US authorities to apprehend him. He therefore communicated with the parliamentarians via a live video link from Moscow.

Bad timing?

Two weeks before the report was on the committee’s agenda for adoption, Islamist terrorists attacked Charlie Hebdo and a kosher supermarket in Paris. Some were quick to call these murderous attacks the ‘European 9/11’. Was it bad timing, then, to present a report calling for fundamental rights and freedoms—including privacy and freedom of speech and information—to be upheld against intrusions by those who are supposed to protect us from the terrorists?

Yet there was not a better time nor place than right after the Paris attacks at the Council of Europe to resist calls for ignoring human rights for the sake of security. Given the tools described in the secret documents leaked with Snowden’s help, total surveillance of all our communications and movements is a real possibility—if not now, then in the near future. But total security is not on the cards, even if we were to give up all our rights.

After the killings in Paris, the German justice minister, Heiko Maas, was invited by his interior minister colleague, Thomas De Maizière, finally to prepare a law allowing for mass data retention. Maas pointed out that such an instrument had long been at the disposal of the French services but this had not helped prevent the terrible crimes in Paris.

‘The whole haystack’

The official NSA portrait of Gen Keith Alexander. Wikimedia / NSA. Creative Commons.In fact, two solid empirical studies on either side of the Atlantic, cited in the report of the Legal Affairs and Human Rights Committee, have shown that mass surveillance has not proved effective in the prevention of terrorist attacks, whereas targeted surveillance has. These studies have shown that those, like the former NSA director, General Keith Alexander, who insist on collecting “the whole haystack” are not really helping the fight against terrorism.

Jim Sensenbrenner, a veteran Republican member of Congress, pointed out that “the bigger haystack makes it harder to find the needle”. And Thomas Drake, a former NSA executive turned critic, said that “if you target everything, there’s no target”. An analysis of the Boston marathon bombing in April 2013 showed that alarm signals pointing to the future perpetrator were lost in a mass of alerts generated by tactics that threw the net too widely.

In short, mass surveillance may actually help terrorists because it diverts limited resources away from traditional law enforcement, which gathers more intelligence on a smaller set of targets. In both the Boston and Paris cases, the perpetrators had been on the radar of the authorities for some time, but the relevant intelligence was not followed up properly because it was drowned in a mass of data. By flooding the system with false positives, big-data approaches to counter-terrorism actually make it harder to identify and stop the real terrorists before they strike.

The report adopted by the PACE legal committee is by no means anti-American. We owe it to an American patriot, Edward Snowden that we are now aware of the mass surveillance and intrusive practices which threaten the privacy of Europeans and Americans alike. European intelligence services deserve a fair deal of criticism too.

Weaknesses

The risk that the mass-surveillance tools developed by the NSA and its allies will one day fall into the wrong hands puts the freedom of all of us in danger. The weaknesses introduced into encryption and other cyber-security measures, to facilitate mass surveillance, threaten the safety of critical infrastructures and even of our bank accounts on both sides of the Atlantic.

Such defects in cyber-security, so introduced or tolerated, can also be detected and exploited by rogue states, organised criminals and, last but not least, the next generation of terrorists—who may prefer sabotaging key infrastructures over shooting off with a Kalashnikov. Sabotage of our electricity supply, air-traffic controls, financial services or the like could wreak havoc on civilisation as we know it.

Most people would refuse to keep a door open at the back of their house, just so the police can check in from time to time to make sure everything is in order. Most would also resist a call to refrain from closing the envelopes of letters they send, or write postcards only, to help the police detect illicit correspondence more easily. In the same way, we should continue resisting ‘back doors’ in information-technology systems to facilitate secret services’ access to emails, phone calls, web postings, location data, surfing history, e-shopping, bank transactions and much more.

Protection

Recent proposals by British and German politicians to place legal restrictions on encryption and other measures of ‘self-data protection’ are dangerous because they would further weaken our protection against terrorists and other criminals. Even now, our data do not seem to be as safe as they should be: if the Chinese were able to access the plans for the next US fighter plane, as has been reported, which data are still safe?

It would not be feasible, politically or practically, to encrypt and secure critical infrastructures whilst otherwise forbidding self-data protection. Where would we draw the line? Would we want to protect our health infrastructures? Our health insurance data? Surely, our bank accounts, too? If our personal communications and related data are ‘fair game’, easily accessible to spy agencies and only slightly less easily to others, how can we guarantee that our passwords and firewalls remain safe?

Most people would refuse to keep a door open at the back of their house, just so the police can check in from time to time to make sure everything is in order.

How can we ensure that our computers are not hijacked, as proudly announced by the NSA in internal documents, for use as sources of ‘plausibly deniable’ cyber-attacks on third parties? When it is so easy to plant ‘compromising’ material on unprotected computers or email accounts (kompromat has always been a favourite of spies, not only the KGB), and when it is so difficult, if not impossible, to prove such foul play (or its absence!), does this not make the prosecution of actual cyber-criminals far more difficult, rather than easier, contrary to the claims of the opponents of encryption? If we want the fight against cyber-crime to succeed—the struggle against hate propaganda and terrorist recruitment on the net, internet paedo-pornography, drug deals, identity theft and all that comes with it—then we must protect the value of digital evidence, not undermine it.

The answer to crime—and terrorism is just another form of crime, namely murder with hate as the motive—is good, old-fashioned law enforcement. And targeted surveillance is, of course, a valuable tool. Cultivating informers, investigating tip-offs, observing potential suspects, finding reasonable grounds for suspicion, on that basis obtaining a warrant to search a suspect’s premises—including, of course, his or her digital abode (computers, email and social-media accounts, phones …)—is how criminals should be caught, prosecuted, convicted and put behind bars. Against this efficiency, mass surveillance is merely a resource-wasting diversion.

Direct threat

From a principled point of view, mass surveillance is also a direct threat to fundamental freedoms as protected by the European Convention on Human Rights, including the right to privacy and respect for family life, freedom of speech and of information, of religion and of the right to a fair trial. The report approved by the committee sums up the case law of the European Court of Human Rights in this respect.

The convention, as interpreted by the Strasbourg court, is binding on all 47 member states of the Council of Europe. In that context, the recent ruling of the UK Investigative Powers Tribunal—which both the plaintiffs, Liberty and others, and the UK NSA ally, GCHQ, have claimed as vindication of their opposing positions on surveillance—does show that the exchange of information between the NSA and its European partners raises serious issues under articles 8 (privacy) and 10 (freedom of expression) of the convention.

The threat to human rights and democracy by the seemingly inexorable growth of the ‘surveillance-industrial complex’ should not be underestimated. As shown in the legal committee’s report, the intelligence agencies of several countries have secured huge and fast-growing budgets. All bureaucracies, especially those intertwined with private business, crave budget increases—providing their leadership with added power, the rank-and-file with more posts and promotion prospects, and private contractors and their lobbies with ever-increasing profits.

Democratic oversight and the usual ‘checks and balances’ provided by the open discussion of pros and cons of government programmes, including the vetting of budgetary requirements, are made extremely difficult by the secret nature of the agencies’ activities. In addition, the technologies used, their effectiveness and the potential consequences are highly complex and difficult to assess for outsiders and technological laypersons—including the elected political leadership and even, it sometimes seems, the top brass of the spying agencies themselves.

Branded

Politicians confronted with demands for additional resources and powers often fear being branded as ‘soft on terrorism’ or otherwise unreliable in the fight against crime. Terrorist attacks which the services failed to prevent are used in support of the quest for more resources and powers. So are the rare success stories (which, upon closer analysis, have turned out to be the fruit of targeted, not mass, surveillance). Thus, the ‘surveillance-industrial complex’ is spiralling out of control and threatens democracy and human rights.

Opposing mass surveillance, far from helping terrorists and other criminals, defends the very open societies, based on human rights and the rule of law, which the terrorists intend to destroy. In April, the debate in the PACE plenary on the report adopted by the legal committee will offer an historic opportunity for the Council of Europe to uphold the shared values of freedom and democracy in the face of the challenge terrorism poses.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.