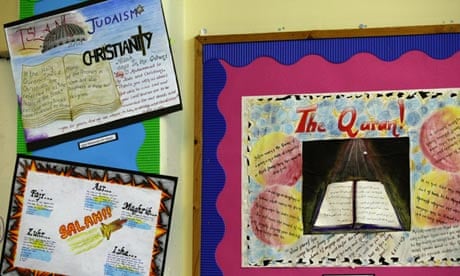

Women bishops, gay weddings, the euthanasia debate, science v religion ... it's time for a reappraisal of Christianity in contemporary religious education. Almost everyone is familiar with the shift over the past three decades from a broadly confessional, Christian-focused approach to the current world religions approach. This is often framed as a move from a Christian traditionalism to multi-faith progressivism.

There is no longer the implicit assumption that everyone is (or ought to be) Christian; instead there is general acceptance of the need to tackle a range of religions and, more recently, secular worldviews in multicultural Britain – and that starts in the classroom. In all of this, teaching about Christianity is often seen as unproblematic, but it isn't.

Unsurprisingly teachers, especially non-specialists in primary schools, have been concerned about both their knowledge of several religions, and the particular issues that surround individual religions. Much policy and research has contributed to better ways of approaching different religions fairly and authentically, and more can always be done: teaching about Islam post 9/11 can be complex, bearing in mind pupils' backgrounds and assumptions; teaching about Judaism can be difficult in the light of the current conflicts. Further, the recent welcome inclusion of other worldviews has also not been well-researched or supported.

There's much evidence showing how teachers have had to navigate through these uncharted waters, where religion and secularity converge. What is the difference between teaching Christianity and teaching about Christianity? The preposition weighs heavily here. It implies an impartial, distanced perspective, but what is excluded? The lived experience of the practice of religion can be missing in a dry presentation of facts.

A recent study by Glasgow University entitled Does RE work? suggested that an understanding of what makes religion meaningful for believers is often lost in the classroom. Another report for (the late) DCSF by Warwick University on classroom materials in RE highlighted the issues concerning how different religions were presented, including Christianity. Plus, Ofsted, and earlier research from Exeter University, highlighted issues for teaching about Christianity.

The diagnosis from all this research suggests five overlapping issues. First, this shift in approach means that teachers are anxious about what they can and cannot say. Their own educational and personal biographies come into play, including their own educational ghosts. Fearful of evangelising, they may reduce Christianity to a series of factoids – labelling the parts of the church, yet not addressing why the church matters to Christians. This is compounded by the fact that confessional, nurturing approaches are seen as being appropriate in church schools, but teachers in non-faith schools may feel that they should veer away from that approach.

Second, while all religions and worldviews are treated in the same way, more time is spent on Christianity as local authorities, which still control the curriculum, often require this. It usually receives more coverage within any school year, and is also the only religion that is likely to be studied from key stage 1 to 4. But researchers and Ofsted found that this extra time could be better spent. Concerns have been raised about how pupils often leave with an incoherent or stereotypical picture of Christianity, or without having been intellectually challenged.

Third, the subject is often essentially seen as being about moral or values development, particularly in primary schools, serving the goal of social cohesion by engendering tolerance and respect. These are worthwhile goals, but they can mean that teachers do not prioritise studying the religions in themselves, opting for a soft generic moral message: the feeding of the 5,000 becomes sharing your lunchbox, not a way of raising questions about "miracles" or whether this belief in miracles still matters to Christians today. Furthermore, pupils cannot develop the essential values for life in a multicultural society, such as tolerance and respect, if they are presented with inaccurate stereotypes of Christians. There is no point in learning to empathise with a cardboard cutout of any religious group.

To enter into the intellectual debates and puzzles, pupils need a nuanced understanding of them. The science and religion debate is a staple part of secondary RE, but needs to go beyond the simplistic evolution v creationism dichotomy to which it is so often reduced. This is therefore not an argument for a content curriculum (200 facts about Christianity) but instead to recognise that we need to encourage pupils to get to grips with more rigorous ways of studying it–tackling its theological, historical, textual, philosophical, ethical, sociological, scientific and ethnographic aspects.

Finally, the teaching of other religions and worldviews is often based on assumptions about pupils' knowledge of Christianity. While more structured teaching of those beliefs is also needed, if Christianity is better taught, pupils will be able to make more nuanced cross-references and comparisons with other religions and views.

If it's so hard then, why bother? There are a range of reasons. Clearly, Christianity is an important part of multicultural Britain: from Anglican Evangelicals to the Black Pentecostalism to Polish Catholicism. It is also a global force: it's hard to make sense of the world today without understanding it. Yet, there are clearly also important traditionalist arguments. You cannot make much sense of British history and culture without it: consider A Christmas Carol without understanding Christmas, or making sense of the English civil war without knowing what Catholicism is. But it is also important that pupils are given intellectual challenges, so that they can confront these issues effectively – more effectively perhaps than previous generations did, for whom religion has become in some instances a bitter and polemical issue.

That is why we at the Department of Education at Oxford University are engaged in the Teaching Christianity in Religious Education project, carrying out research and developing online materials to support those teaching RE in the classroom. These are based on our wider departmental work in teacher education and professional development. This will help teachers develop their own practices towards a more nuanced secularity, based both on the pupils' right to an education about all aspects of the world around them and on their right to freedom of belief.

Ultimately, we hope not to change the current model of RE, but to improve teaching about Christianity within it.

Dr Nigel Fancourt is a lecturer in the Department of Education, University of Oxford. He is the lead researcher in the Teaching Christianity in Religious Education project.

This content is brought to you by Guardian Professional. Sign up to the Guardian Teacher Network to get access to more than 100,000 pages of teaching resources and join our growing community. Looking for your next role? See our Guardian jobs for schools site for thousands of the latest teaching, leadership and support jobs.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion